The Next Life – Bernard Butler Interview

From Britpop guitar god to behind-the-scenes production wizard, Bernard Butler’s career has certainly been varied. Andy Price takes a look round his studio, finds out about his current projects and hears the truth about that break-up… Photography by Mike Prior “I’m not an engineer, I don’t just press record for people – there’s got to […]

From Britpop guitar god to behind-the-scenes production wizard, Bernard Butler’s career has certainly been varied. Andy Price takes a look round his studio, finds out about his current projects and hears the truth about that break-up…

Photography by Mike Prior

“I’m not an engineer, I don’t just press record for people – there’s got to be a reason for me to be involved creatively,” declares former Suede guitar hero and songwriter Bernard Butler. We’re here in his impressively geared, but somehow still quite cosy, Studio 355, the nerve centre from which he runs his multi-faceted career as established producer, songwriter, guitarist and creative guru.

Bernard is currently in the midst of multiple projects – including recording with his improvisational band, Trans, and working alongside Everything But The Girl’s Ben Watt on his latest record and upcoming tour. We caught up with Bernard to discuss his approach to music making, his studio technique and his varied musical history…

MusicTech: Is it right you were previously a sit-in tenant at [Orange Juice frontman] Edywn Collins’ West Heath studio before setting up on your own?

Bernard Butler: Yes, Edwyn was ill and in recovery from his stroke, so for a few years I was there and did quite a few records. Then of course Edwyn improved and wanted his studio back, so I came here and set up Studio 355 [named after Bernard’s signature guitar of choice, a 1961 Gibson 355]. A lot of the actual recording gear I’ve had for a long time, I haven’t really bought a lot of stuff. I do see gear in mags sometimes and I sort of think ‘yeah great, that’d be brilliant for my studio,’ then I kind of wonder if it’s worth it. I mean, will it all really make a difference to my studio and the way I work.

MT: You’ve worked with a wide variety of musicians including Duffy, The Libertines, James Morrison, Teleman, and Kate Nash. How do you get involved with new production projects?

BB: I don’t really seek people out. I don’t assume that if I go up to someone and say ‘hey you’re really cool, come to my studio,’ they would instantly come and work with me. I always think that if someone’s good then they’ve worked hard and have an idea of what they’re doing, and have someone to work with already.

In the past people have generally come to me, for one reason or another. Sometimes it’s to do with writing, so I’ll do a writing session with somebody and that will become a production. I get sent stuff, and if I like it then I’ll get involved. It’s as simple as that. So more often than not I work with new, developing artists.

Introducing the Band

MT: In terms of gear, what’s the cornerstone of your studio?

BB: I’m still using Pro Tools 9, which I know is a little outdated. Basically I got loads of plug-ins for free and I’m a bit scared to go back to them and ask to upgrade it all and go through the set-up learning process again. I’m used to Pro Tools 9 and the simple fact is that it just works for me.

Bernard is widely known for his superb guitar chops, but he’s also a dab hand with the piano and synths…

A couple of times I’ve looked at it and realised that I’d have to spend a grand just to get that thing where you can draw in the gain – and I’m not sure it’s worth it? Would that really change my life? Or would it mean I’d spend a week trying to set it all up and take precious time away from music making.

Really, I’ve got more than enough features in Pro Tools 9. There’s a danger of limiting creativity, I think, with having too much to play with, and that goes for both software and gear. With my setup everything just works well for me.

MT: What outboard hardware do you have?

BB: I’ve used Thermionic Culture stuff forever. I’ve got the Earlybird, which was one of the first ones. I know Vic [Keary, Thermionic Culture’s head honcho] and I also got sent a prototype of the Phoenix from Nick Terry, a great engineer who designed it all originally. I’ve also got a Culture Vulture – I use it for everything I record. They’ve also got some pretty good plug-ins – they just make really great stuff!

Trans-ition

MT: You’re currently working with former Everything But The Girl frontman Ben Watt – is that as a producer or as a musician?

BB: With Ben my role is quite straightforward – I’m just playing guitar. I’ve not been involved in the production or the writing in a significant way, I’ve just been adding bits here and there. It came at a really nice time when I’d done a lot of writing and production work and was starting to feel a little bit jaded by it all. But when Ben asked me to play guitar that was brilliant, because the whole thing was his problem and I just got to ride along!

Ben will sometimes says to me, ‘you see that chord there, don’t play that,’ and that’s so refreshing. I’ve worked with people over the years who would say, ‘but that’s my chord, I always play that chord,’ and get really touchy. I’d rather eliminate those problems during the making of the music rather than seeing it written in some horrible review. You’re a better person for it, I think.

MT: Your band Trans is quite experimental and progressive – how does the writing process work?

BB: We have three days of playing non-stop, then leave it a month and come back and do the same thing again. We’d all be in our various positions and someone would just start playing and we’d all kick in and start adding to it, evolving it.

I’d press record the minute everyone was in the room and set up so that every single note was down. I’d then go through the recordings and realise that most of it was utter bollocks! However there’d be one or two little riffs, melodies or patterns that were really, really good, or two minutes at the start that were really cool. So I’d be isolating the hooks, and me and Jackie [McKeown] would sit here and experiment, putting bits and pieces together in Pro Tools.

We wouldn’t chop them out of the multi-tracks but we’d approach the recording as if it was two-inch tape. We’d cut the whole thing out, so everything then stayed as it was rather than editing it all together again. It’d be more akin to splicing. We’d do that again and again and put vocals on the top. Occasionally we’d re-record certain ideas better later on and layer them on top.

Bernard with his trademark Gibson 355 – a guitar so good he named his studio after it.

MT: Is there a specific goal you’re trying to achieve with this way of doing things?

BB: The key thing is that it’s the sound of the room that we all liked. That’s why some of the tracks fade in and fade out – we were deliberately limiting ourselves. We all agreed that the primary spirit of Trans is that if we’re enjoying it, then great, and we don’t really care if people dislike it. The whole reason we started was to get in a room and play!

Master Craftsman

MT: Do you see yourself as a producer or a musician these days?

BB: I still think of myself primarily as a songwriter and music maker more than a producer. Normally I’ll start with a musical idea at the piano. My piano over there is brilliant, and it’s great for getting rhythm ideas down. It’s good for thumping out bass notes, giving you an idea of rhythm straight away.

From there, once I get an idea going or a melody I’ll switch instruments, perhaps to the guitar or drums, decide what other elements I can add and start capturing something. Production goes along with the writing for me – if the song is intended to be an acoustic song or just a piano-based song then that’s fine, but even when I do that there’s some measure of production.

Production is as important a part of the composition process as writing with an instrument, I think. I have started a song digitally with loops on Pro Tools, but more often than not all my songs start on the piano.

MT: Will you usually play all the instruments yourself when you’re working up demos?

BB: Yes, even the ones I can’t play that well. I can’t play the drums but I know exactly what the drums should do when I’m writing songs – I know exactly what I want, but when I go in and try to do it myself it never works out too well! But I do record little loops of things, ideas, etc, because it’s the quickest way of getting them down.

Bring it Back

MT: You’ve had such a varied career – is there one particular high point that towers above all others?

BB: It’d probably be, and I always say this, Yes by McAlmont & Butler. After all this time it’s still always that. It kind of puts down everything else I’ve done by saying that, but I do love lots and lots of things that I’ve done in the past.

Obviously Suede was a massive thing for me and probably what people ask me about the most, but writing that song with David and pulling it off at the time was such an amazing feeling. The song itself still makes me really happy, and gives people a lot of joy.

The kind of studio rack that every guitar hero needs!

Basically, when we did that I had just come out of Suede and I really didn’t want to form a new group. I wanted to make some music that was outside of the constraints of being in a band and all the stuff that goes along with it – T-shirts, fanzines, press attention, and the rest. All I wanted to do was just make the best music I could, and with Yes the idea was to make a perfect pop moment. I was really obsessed with making a pop moment at that point in time.

MT: You recently performed with David McAlmont at a couple of fund-raising shows at the Union Chapel in Islington – how did they come about?

BB: Me and David never actually split up, and we’d played gigs in the interim period. What happened with the recent big shows was that I’d run the marathon and was trying to raise some money for charity. We decided to play the Union Chapel thinking that we’d sell 300 tickets and it would look OK and it’d be a good laugh, and actually it sold out in five minutes!

We sold a thousand tickets in five minutes. The second night, the same thing happened. I think we were all taken aback by that. The shows were really great fun. It was that really rare moment where you go on stage and play a song and you just feel like you’re not really playing.

We played Yes and I just looked out at the audience and thought that it was the easiest thing I’ve ever done. I’d just ran a marathon, which was a nightmare, and I thought ‘why the hell don’t I just stick to this!’ It was a really beautiful moment. It’s a very rare thing to write a song and see people genuinely loving it – that feeling of making someone’s three minutes better is unbeatable. That’s what music means to me.

The Wild Ones

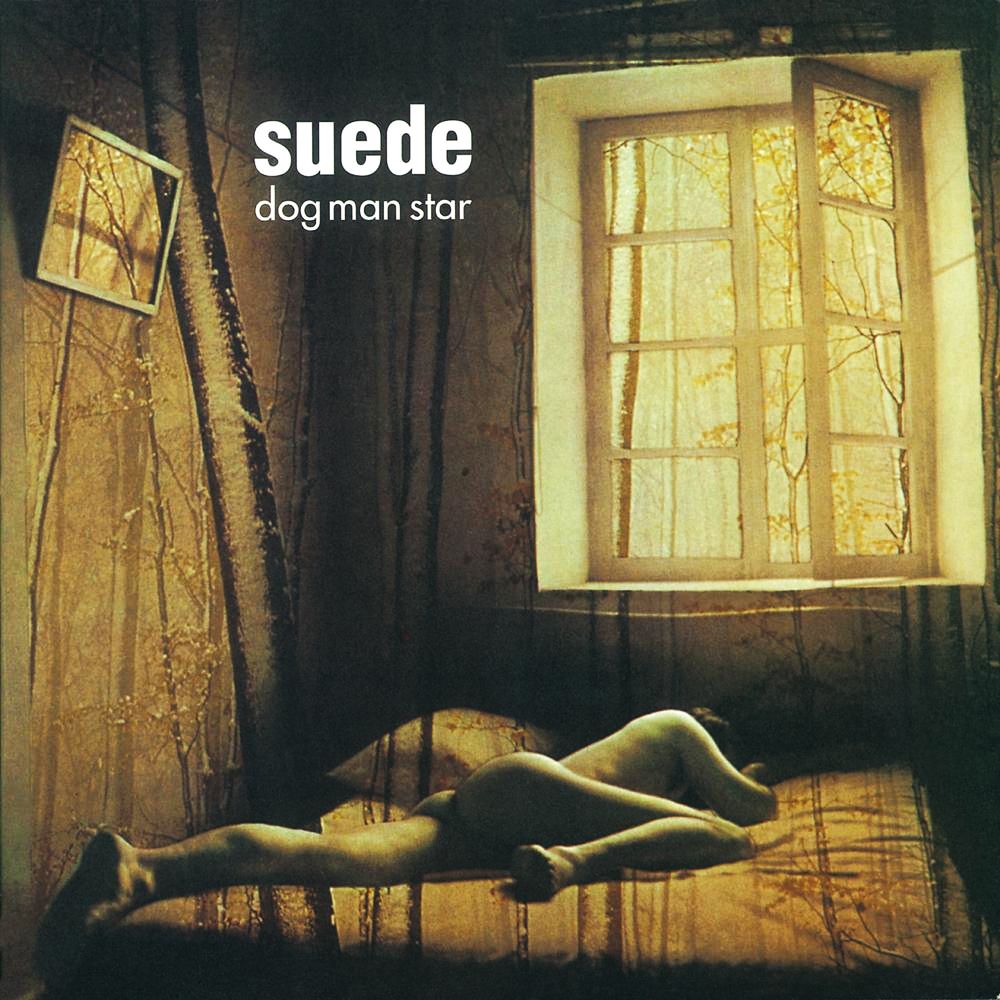

MT: Twenty years have passed since Suede’s Dog Man Star was released, which was the point that you left the band. Many people claim to have the ‘inside story’ behind the fall-out that occurred between you and Brett Anderson [a rift which has subsequently been healed], but what actually happened?

BB: I’m really proud of Dog Man Star. I was proud when I was writing it, when we were recording it, and I was proud of being part of the band at that time. I thought it was fantastic all through the process.

It’s very difficult to talk about it because there’s so much written into folklore, as there always is about these things, and it seems that no matter what I say people seem to go ‘yeah, yeah, yeah,’ and then they’ve still got all the myths and untruths about my departure from Suede in their head.

I’ve tried so many times to explain the truth of that situation to people. Dog Man Star had to have an anger and an atmosphere, an emotional core and a deep sadness – that’s what we were trying to convey. Brett [Anderson] left it to me to create music that would inspire him, and I’d spend whole days writing songs. I was in a really creative mindset during that period and the tracks would come one after the other, and I’d get them quickly down onto a four-track recorder. Once every few days I’d take them round to Brett so he could work on the vocal parts.

It’s not true at all that we used to just communicate by post. It probably happened once because one of us was away somewhere, but it’s a complete fabrication that we were distant – I’d go round to his flat in Highgate. And he did not live in a Victorian mansion – again that’s completely made up by the myth-makers. He lived in a flat on Shepherd’s Hill!

The album in question – the making of Suede’s 1994 masterpiece Dog Man Star was fraught with internal difficulties, but as Bernard reveals – it was a disagreement about the record’s mixing that ultimately led to Bernard’s departure

MT: So was the recording process as fraught as some would have us believe? Or was it just a difficult record to make musically?

BB: Well the recording process was interesting, it was very intense music. Actually, thinking about it, I wouldn’t call it dark. I don’t view Dog Man Star as dark at all, but it’s very intense and very emotional. Songs such as The 2 of Us and Black or Blue are often referred to as such and they really aren’t particularly dark songs, we just thought they were beautiful little compositions. Brett basically wanted me to push myself to the limit and I certainly assumed that he would as well.

Unlike a purely commercial studio, Bernard has to have a creative stake in a project before he gets involved.

MT: Is there any truth to the rumour that you wanted to take more of an active role in the production side of Dog Man Star?

BB: People often say that part of the reason I left was because I wanted to produce it, and that’s not true at all. I never ever wanted to produce Dog Man Star. I didn’t ask to, nor did I attempt to mix it myself. Again, another myth that has somehow become fact.

What I did say was that I wanted somebody else to mix the record. Halfway through making the record I’d been playing the stuff to producers, engineers, people at the mastering room, and they all said the same thing – this record should and could sound better. I didn’t see the harm in getting someone else to mix it, and just work with someone else to get the sound of the record better. And the album’s producer, Ed Buller, has since admitted exactly the same thing.

That’s all I wanted to do, and that’s where the friction got too heavy. I was told that it was never gong to happen. But I was serious about it and I knew exactly what I was talking about. To this day I still think it would have been better, and Ed has said the same.

When push came to shove, though, it spiralled out of control and became a thing where, like everything with Suede, I took it to the edge of the cliff just to see what would happen. And when you do that you have to be prepared to jump when you get there. This was how we ran our lives and we were in this mindset this anyway. When the crunch happened I said, ‘OK, well I’m standing by my point and I’m going to jump,’ and they said ‘go on, then’ and so I did. And that’s why it ended, it’s as simple as that.

The glory days – Bernard first shot to fame with a blistering salvo of singles with Suede in the early 90’s that achieved massive popularity and kickstarted a movement that eventually became known as Britpop.

MT: Given the large amount of time that’s now passed, how do you view that period now?

BB: I think it’s quite funny, really. Lots of people saw my departure from Suede as sad, and I know Brett sees it as sad. But actually it’s just really funny when you think about it. We’re not talking about fighting wars here, we’re talking about making records. It’s all about what we could do as people creatively – you know, it’s just a pleasure to work in music full stop!

Click Here to For Bernard’s Studio Tour

Click Here to read Bernard discuss his guitar playing approach and collection