Celldweller Interview – Going Underground

The mastermind behind cyberpunk act Celldweller, Detroit-based Klayton has helped drag electronic rock kicking and screaming into the future. MusicTech enters the Celldweller spaceship… As a teenager, Celldweller’s Klayton could barely afford to purchase the hardware that would allow him to indulge his love of European new wave music. Instead, he adopted the guitar in […]

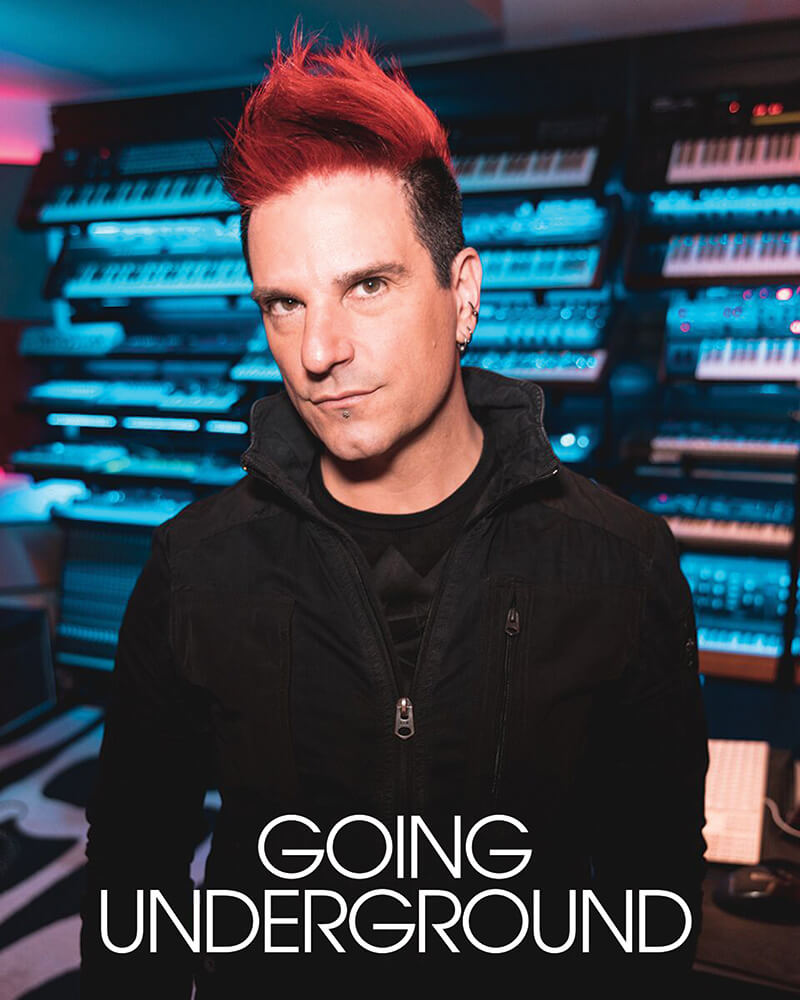

The mastermind behind cyberpunk act Celldweller, Detroit-based Klayton has helped drag electronic rock kicking and screaming into the future. MusicTech enters the Celldweller spaceship…

As a teenager, Celldweller’s Klayton could barely afford to purchase the hardware that would allow him to indulge his love of European new wave music. Instead, he adopted the guitar in a bid to emulate his favourite metal bands and as the ’80s evolved, embraced the rudimentary technology that would allow him to amalgamate rock and electronic elements.

Since then Klayton has risen left of centre to become a highly skilled and accomplished producer, responsible for a raft of pseudonyms that also include FreqGen, Circle of Dust and Scandroid. Through these distinct identities, the Detroit-based innovator has combined elements of metal, electronic rock, EDM, drum and bass, trance and new wave with staggering assurance.

Beside his own output, Klayton has produced music for multimedia, film, TV and video games. Meanwhile, his production skills, predicated on an enduring passion for technology and detailed sound design, are brought to life in his stunning multi-room studio, featuring a litany of hardware pedals, synths and the latest modular gear.

You grew up listening to ’80s new wave. Which artists most stood out for you?

I listened more to metal than new wave. I was into new wave in the ’80s, but I grew up on Metallica and Slayer. But even before that, I remember hearing the vocoder on things like Mr Roboto. from Styx and being fascinated by how a human voice could sound like that. My first real project, Circle of Dust, was an industrial metal thing. I started fusing electronics and metal because I knew both of those worlds and it made sense in my head to amalgamate them.

You picked up a guitar rather than a synthesiser due to affordability?

My mother got one of my brothers a $100 guitar. It was a piece of crap, but that didn’t matter because it was the only one in the house. I would jam in bands and when I finally discovered power chords, I’d sit for hours trying to learn how to play them. At that point in life, it was out of the question that I could afford a synthesiser.

Absolutely, it was a great excuse for me to scratch those itches that I had from the ’80s. The first album I covered was Shout by Tears for Fears. These guys were role models to me, along with bands like Depeche Mode, The Cure and Howard Jones – the list is a mile long. My Scandroid project is really just about me wanting to make new wave music. When I create for that project, I imagine myself making music that sits next to the artists I liked from that era.

You have four identities, Celldweller, Scandroid, Circle of Dust and FreqGen. Do you have a clear idea in your head of what these projects represent or do the lines get blurred?

I have boundaries. It’s just my way of delineating these sounds between four different projects. Currently, I’m working on a new Celldweller album, so I get into Celldweller mode. The boundaries don’t restrict me; it’s more about the set of tools I’m going to use.

For Celldweller, I’m not cracking out my Juno-60 or 106, and although I can use those synths, I wouldn’t use them in the same way I would with the Scandroid project. I’m relying more heavily on guitar, my vocal style is different and that whole world is more influenced by drum and bass and psytrance.

When did your electronic gear journey start? Can you remember your first purchase?

Yeah, I remember it vividly. My first project was Circle of Dust, but before that I managed to borrow my parent’s credit card. I knew a kid who had a Roland D-20 and he introduced me to programming. I was like, wait a minute, I can play beats into this thing, hit the play button and it will play them back? So I hustled and did a newspaper round to buy a D-20 and make music.

Eventually, I got signed to a small label, which didn’t end well unfortunately, but I told them I was doing an industrial project that was highly reliant on sampling and didn’t have a sampler. They got me an Ensoniq EPS-16+, and to this day I still love that sampler.

How did that change things for you?

That sampler opened my world to so many possibilities. So much so, that I went back into debt in order to get a Mac Classic, which had a 40MB hard drive and 1MB of memory. I ran some software on it called Vision, which later became Studio Vision Pro, and used that to do the MIDI functioning, programmed from the Ensoniq.

Then I wrote riffs and created vocals over that. In those days, I’d go into the studio and do 10 songs in 10 days, tracking guitar, bass, vocals and any extra synth parts in a very short amount of time, because I was the only one making the music.

There was no YouTube in those days. Do you think the plethora of information available now is genuinely helpful?

I look back now and think if I had the YouTube tutorials then that are available now my production chops would have grown immensely in a very short space of time. But I also think that would have affected my creativity, because what you see now is a cookie cutter mentality.

For example, everyone is watching FL Studio tutorials and going out and making clones of the exact same music. It’s a by-product of the accessibility of these things, but back in the day I had to read manuals, which I didn’t enjoy, but I was so hungry for the information.

When I got my Ensoniq, I read the 500-page manual two or three times, learned that sampler inside out and could make it do anything I wanted. I squeezed every bit of functionality out of very little gear. I literally made three albums using just the Ensoniq, a D-20 and the Mac Classic, and spent a lot of time programming and creating the soundscapes.

Will it make you a better producer if you intrinsically understand how the gear works?

If you take a guy like Tricky, he’s a great producer but he’s also said that how he doesn’t understand music and that he does everything by ear. So you don’t have to know what reverb or compression is to make good music. A lot of kids get caught up in the ‘how to’ and forget to just do. To be honest, I didn’t understand what a soundwave looked like because my sampler didn’t have a graphical display.

It was just an LED with 20 characters of text, so if I wanted to change the sample start time, I was looking at a string of numbers that represented the sample length rather than a waveform. Everything I did back then was by ear.

You have an amazing studio. How has it developed into what it’s become today?

I’ve always had gear, but for a long time I worked in basements and cellars. That’s how I came up with the name Celldweller, because my mother would tell me off for not coming out of the cellar. I finally got a place in 2007 and built out a 2,400 sq. ft. space with multiple rooms.

It took me two years to build, so in the meantime I made music in my spare bedroom at home. I even had my AWS900+ SSL console in there [laughs]. My current studio has only looked really impressive over the last couple of years when I started gathering a lot of modular stuff. I’m really into the sound design and routing capabilities of the modular environment and I also have a lot of synths and samplers because I love what they do.

You’re using ADAM audio monitors. Why use those monitors specifically?

I got my ADAMs at Vintage King, which sells high-end gear. I went there and did a monitor shootout, throwing the ADAMs up against some Barefoots and a couple of others. But I kept coming back to the PS33As because they sounded the most full, but flat, so it didn’t feel like they were colouring my sound. They didn’t have a sub, but had enough bass to create a good all-in-one speaker setup. Later, I added an ADAM sub in my main room along with two or three other ADAM setups – the A5, A7 and AX range, because I also have a synth room and a couple of editing suites.

How much importance did you attach to soundproofing?

Actually, I don’t, primarily because I’ve worked in completely untreated rooms for most of my career. They were rectangular rooms, and you can’t get any more reflective than that. If you can make a mix sound good in an environment that doesn’t sound good, it’s going to sound good almost anywhere.

Since I had the ability to soundproof my studio, I treated it to break up the reflections in the room so that I don’t have frequencies bouncing around that are messing up my perception of the bass.

But if you want to learn about your environment, all you have to do is pull up music by other bands you’re familiar with and start to learn that way. If you spend too much time thinking that you can’t make music then you’re not going to create anything.

You mentioned the AWS900+ SSL desk. Will you typically feed your hardware straight into the desk?

I have a pretty substantial patch bay, so right now things are wired directly into the desk, but I do have the ability to break that routing at any point and run stuff through my Neve 1073 preamp or Universal Audio 1176 limiter.

I also have a bunch of Avalon channel strips and some API stuff, so depending on what I want to pull out of my gear, whether it’s modular or a guitar, I can intercept it at source and run it through outboard and into the desk. From there, I bounce it into Cubase.

You have a ton of pedals and effects modules?

They’re tools that make you think in a different way, because they allow me to do things that I can’t always pull out of a plug-in. I created a guitar tower that’s become my sound design haven. Sometimes I plug synths through them and get great results. I’m usually looking for the more extreme stuff that will allow me to tweak things in different ways.

Strymon make awesome-sounding reverbs, delays and modulation sources and I really dig EarthQuaker’s devices. They make great pedals, from distortions to compressors, delays and reverbs. I’m working on a new track right now and ran my guitar through an EarthQuaker Arpanoid pedal to create an arpeggio that’s running through a whole section of a track. If you heard it, you’d think it was a synth.

Is it the fun of using them that’s appealing or about balancing your use of software and hardware?

With those things, I can’t really synchronise them to an external clock, so I’m doing it all by ear. That’s how music was made in the ’70s and ’80s, when you didn’t have a DAW sending out master clock to the analogue delays.

There’s a magic in that, because now everything is so perfect and sterile that you don’t have to work very hard to get a cool-sounding delay. You have to work much harder to get an analogue delay to sound like it’s in time than a digital delay, but there’s a beauty to that, especially when those things drift out of time.

You mentioned Cubase. Has that always been your choice of DAW?

When Vision became Studio Vision Pro, the guitar company Gibson bought the company that made it, Opcode, and basically killed it. So I became a Pro Tools user. I used it for a long time, but I’ve been using Cubase for six years now and couldn’t be happier. For me, it’s a better environment for creativity and it feels like home. There were a few outstanding things about Pro Tools that I used to love, like automation, but now Cubase have added that.

You’ve separated your modular from your synth racks. Is that because modular is your primary creative tool now?

No, I just think that the modular stuff integrates more directly in my main room. I can run guitars through them, or synths. I’ve got another Cubase rig in there and like having the ability to go in and get into a different mindset. I can open up my session over the network and start tracking the synthesisers within the same sessions. Then I’ll jump back into the main room, open up the session and it’s all there ready for processing.

Which synths are still key for you?

It’s really excited to own an Oberheim OB-Xa and still use that a lot. I also have a Roland Juno-106 and Juno-60, which have a very specific sound to them, two Dave Smith Sequential Circuits Prophet 600s and the newer Dave Smith and Tom Oberheim OB-6, which I use on a lot of stuff because it has the convenience of USB integration. But for the most part, my synth room has a lot of old synthesisers like the Korg Mono/Poly and the PolySix.

The Swarmatron looks like a particularly nice piece of vintage kit?

It’s a great sound design tool that does something very unique. It has eight oscillators, but only a few of the models, as far as I know, have FM capabilities. So I have the ability to frequency modulate any oscillator to the other remaining oscillators. Basically, there’s a big knob that allows you to detune these oscillators, which makes it sound like a swarm of bees, but I’ve used it to create bass lines because it’s an oscillator beast with some really good resonant filters.

The Moog Vocoder looks interesting too…

That was a very expensive purchase. Originally, the only vocoders I could afford were software. I had a Boss SE-70 multi-super effects processor, which had a vocoder in it, and I used that on my early Circle of Dust albums. Now I’ve got a Roland SVC-350m, which is a rackmount version of the VP-330 and the Moog Vocoder.

Modular has increasingly become a feature of your studio. Is that in reaction to software?

I do think it’s a reaction to software. Back in the ’80s and ’90s, when that stuff was the only option producers had, the second that the Yamaha DX7 came out and you could store presets and recall hundreds of sounds, analogue gear started going out the door.

People were leaning towards the precision of digital and the advent of the DAW and VSTs blew open the door for digital as you could produce an entire track on a laptop. There was a mass exodus from analogue, but I think a lot of producers are thinking, ‘OK, I’m using Massive, as are thousands of other producers, but everybody’s starting to sound the same’.

It’s strange because software can produce an almost infinite amount of sounds. Are people not using it to its maximum capacity?

I wouldn’t want to call out any other producer, but there are guys that just want to grab sounds and produce tracks they can play out quickly. Whatever a person’s motivation is up to them and

it goes without saying that hardware is more expensive than plug-ins.

So why go back to hardware?

Because you can do something other producers can’t. The thing about modular hardware is that you never get the same sound twice. It’s not as precise as synthesisers in the box, but you can get everything from dirty and gritty atonal rhythms right down to beautiful arpeggiations and ostinatos out of a modular sequencer.

I don’t use modular just for synthesis either, most of the sound design on my last Celldweller album, End of an Empire, came through my modular setup. I was running bass, vocals and guitars through them and a lot of the synth parts originated from the modular system.

I got into modular about five or six years ago and I’ve definitely learned things about synthesis and sound that I took for granted. I learned the basics of synthesis and how signals flow and did some things wrong, which sometimes produces pretty cool results.

What about the timbre of the sound? Is that a clear differentiator?

In the box sounds have come a long way. Arturia makes the V Collection, which are emulations of classic synthesisers and I use it all the time. But there is definitely something about analogue’s low end that you don’t get in the box.

Is it difficult to know what you want without having a deep knowledge of it?

When I started, I had to dig around YouTube and it was terrible. There were no explanations, or the tutorials assumed that because they knew how it worked, the viewer would. I would basically have to watch them and reverse engineer everything.

Now you can follow guys like DivKid on YouTube who will break down the basics all the way up to advanced techniques, and if you want to know what piece of gear to buy, you can create an account at muffwiggler.com and read the forums. YouTube is your friend and most of these modular companies are making demo videos of their products. When you watch a video and can see and hear what something does, it enables you to determine whether it’s worth getting.

You have a Buchla 200e System. How does that differentiate from your Eurorack modules?

In a number of ways, because the Buchla setup is very different to the Moog setup. In the ’70s and ’80s, Moog was much more musical, so musicians tended to gravitate towards it, whereas Buchla was always more experimental. It’s just a different way to think about how oscillators work, as there are no real filters in a Buchla environment per se, and the sequencers work in different ways. Compared to Eurorack or an analogue synth, I end up with totally different results when working within the Buchla environment.

For sound origination, what role does software play in your production process?

I probably use software more for the effects side of things. Occasionally, it’s simpler to use a preset sound but for effects I’m a huge fan of the FabFilter suite and their Pro-Q EQ plugin is pretty much on every track or session I make. Soundtoys make some great plug-ins and there are many companies, like D16 Group, which makes a bunch of really unique synths. Their 303 and 909 drum machine emulations sound great because they’re very warm and thick.

I read that you were developing your own Solaris software?

It was renamed ’Transport’ and it’s now out as a Native Instruments Kontakt instrument. It’s got over 2,000 loops that were primarily made using my modular gear. There’s also a bunch of modular sample packs and a lot of stuff is set up for film scores with step sequencers built into it. If you go to refractoraudio.com, you can get all the information you need.