How video game tech has taken music-making to another level

There’s been a converging relationship between gaming tech and music production over the last few decades. We find out more…

Image: Shutterstock

As this magazine is called MusicTech, I’ll presume you make music – not much of a leap. But it’s also a fair bet that most of us have played games at some point or another, too, whether it’s been a casual dip into something a friend was playing, or it’s 50-plus hours a week on a massively multiplayer roleplaying game.

While we’ve spoken to a huge range of people who compose and create music for the gaming industry, there’s also another aspect to the relationship between music and video games – namely, the many ways to adapt the hardware and sounds involved in gaming for our music projects.

As this is such a fertile and constantly developing area, there’s not really a right or wrong to this – there are so many ways we can interact with our music gear. Plus, in some ways, the history of gaming is also the history of sound design and hardware control – from joysticks to VR, and from 8-bit crunch to surround sound. So with this in mind, let’s explore a selective chronological history that documents this entertaining and creative relationship between games and music production, with an emphasis on the key developments, and finish up by looking at the current state of the art…

Meet six electronic music creators who are inspired by video games

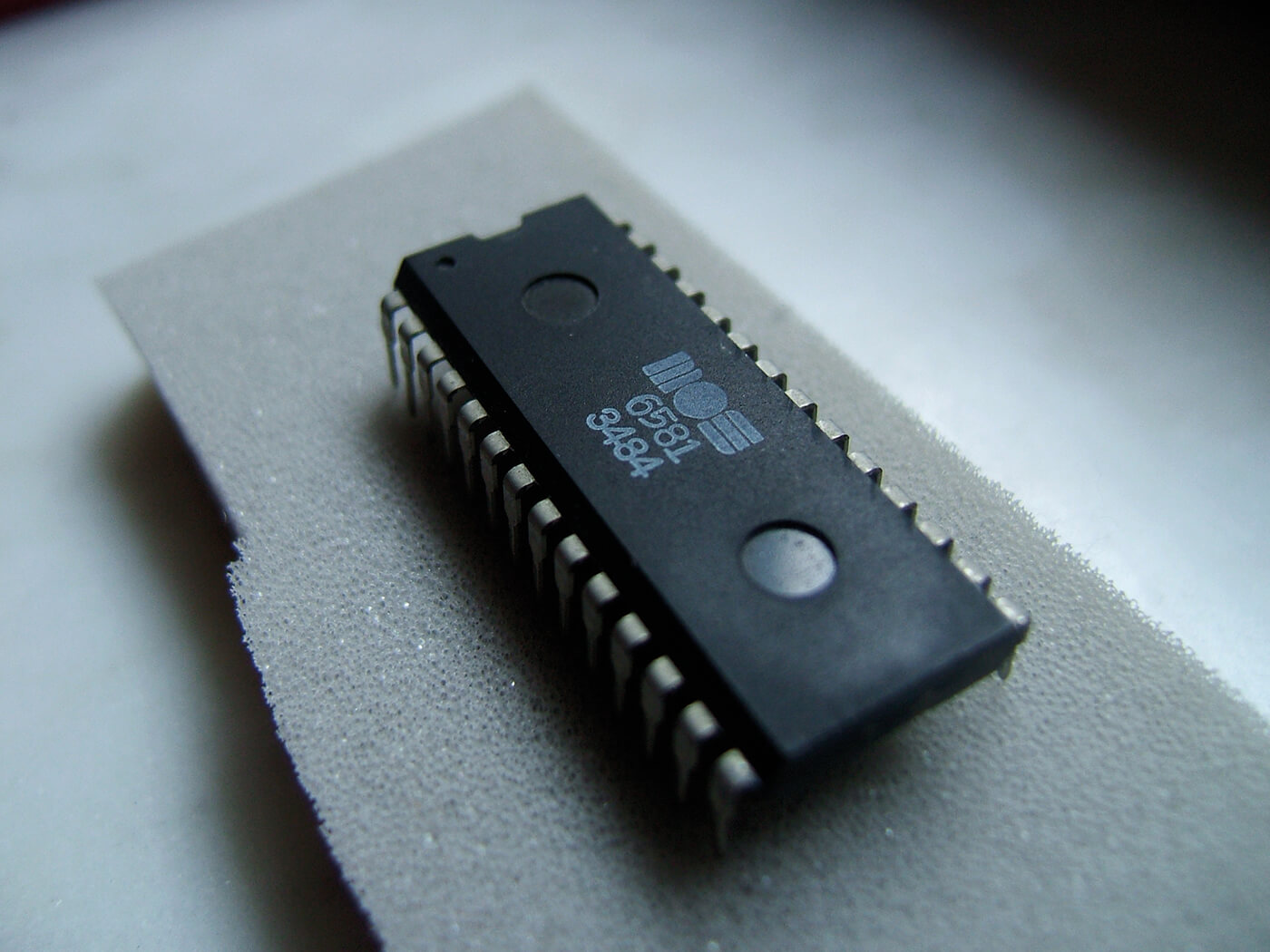

The Sid Chip (1982)

Back in the early days of gaming, composers were working with very limited toolkits, but some of those very early games had incredibly catchy soundtracks. The Commodore C64 was a major progression in home computing, and part of the appeal was due to the MOS Technology 6581/8580 SID (Sound Interface Device) chip. Synth scholars will recall that the SID project was headed by Robert Yannes, who went on to co-found Ensoniq. The SID chip included three-voice synthesis, with five waveforms, or combinations of those, as well as ring modulation and a filter. You can’t buy the chips anymore – more on that shortly…

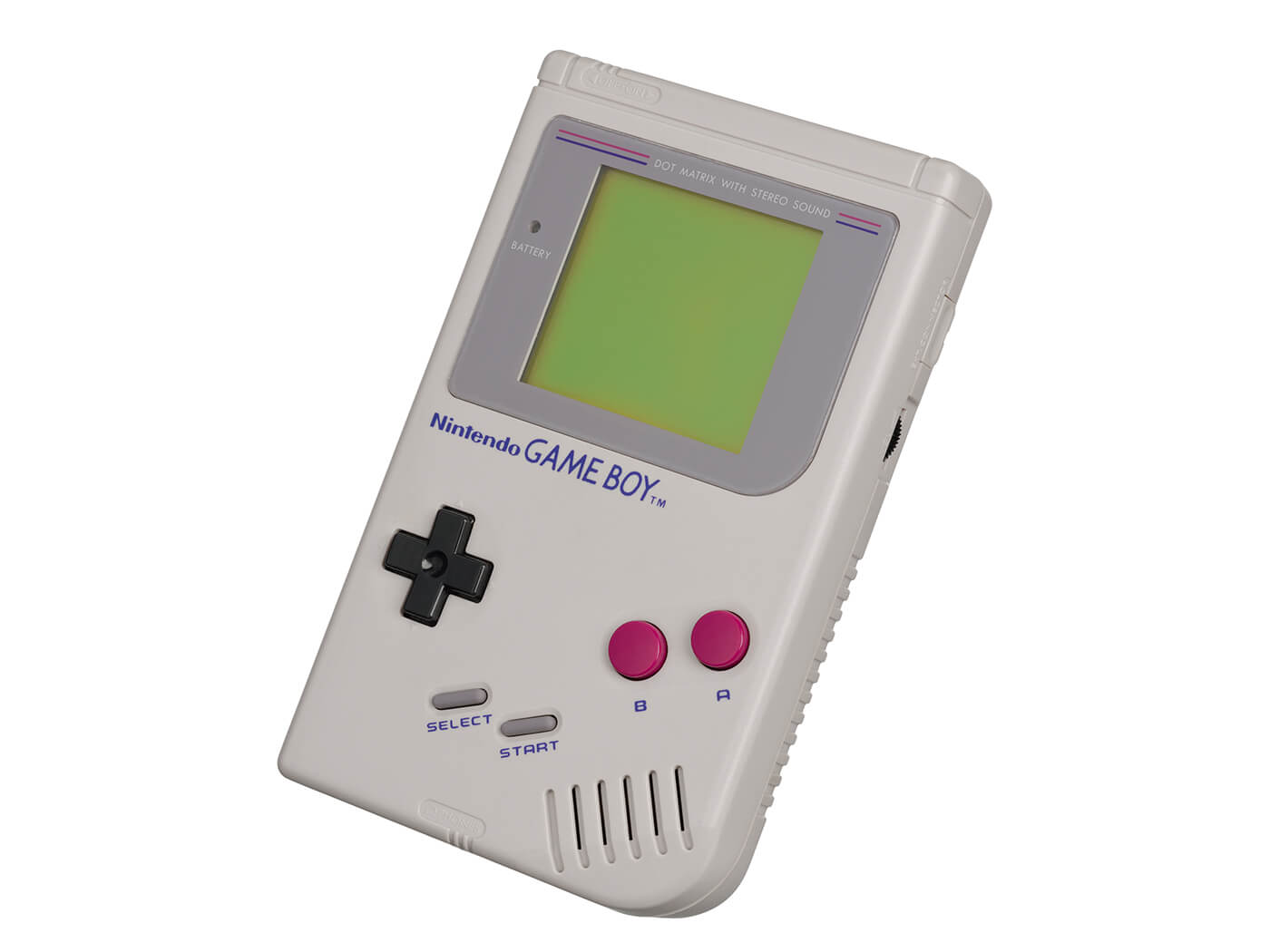

Nintendo Game Boy (1989)

Seven years later, the Game Boy brought glorious low-res sounds to millions of players. 2016 saw a custom Game Boy music cartridge called Nanoloop, with a sequencer and synth from nanoloop.com. We’ve seen people play entire sets with this, and it’s surprisingly effective.

If you don’t own a Game Boy, Nanoloop is also on iOS and Android – and in computer-land, there are a number of Chiptune-style plug-ins that’ll emulate the sounds (eg, Super Audio Cart from impactsoundworks.com, and Chipsounds from plogue.com). There’s supposedly a reissued Game Boy coming soon, with an aluminium case, and rechargeable battery, which retains full compatibility with the original cartridges.

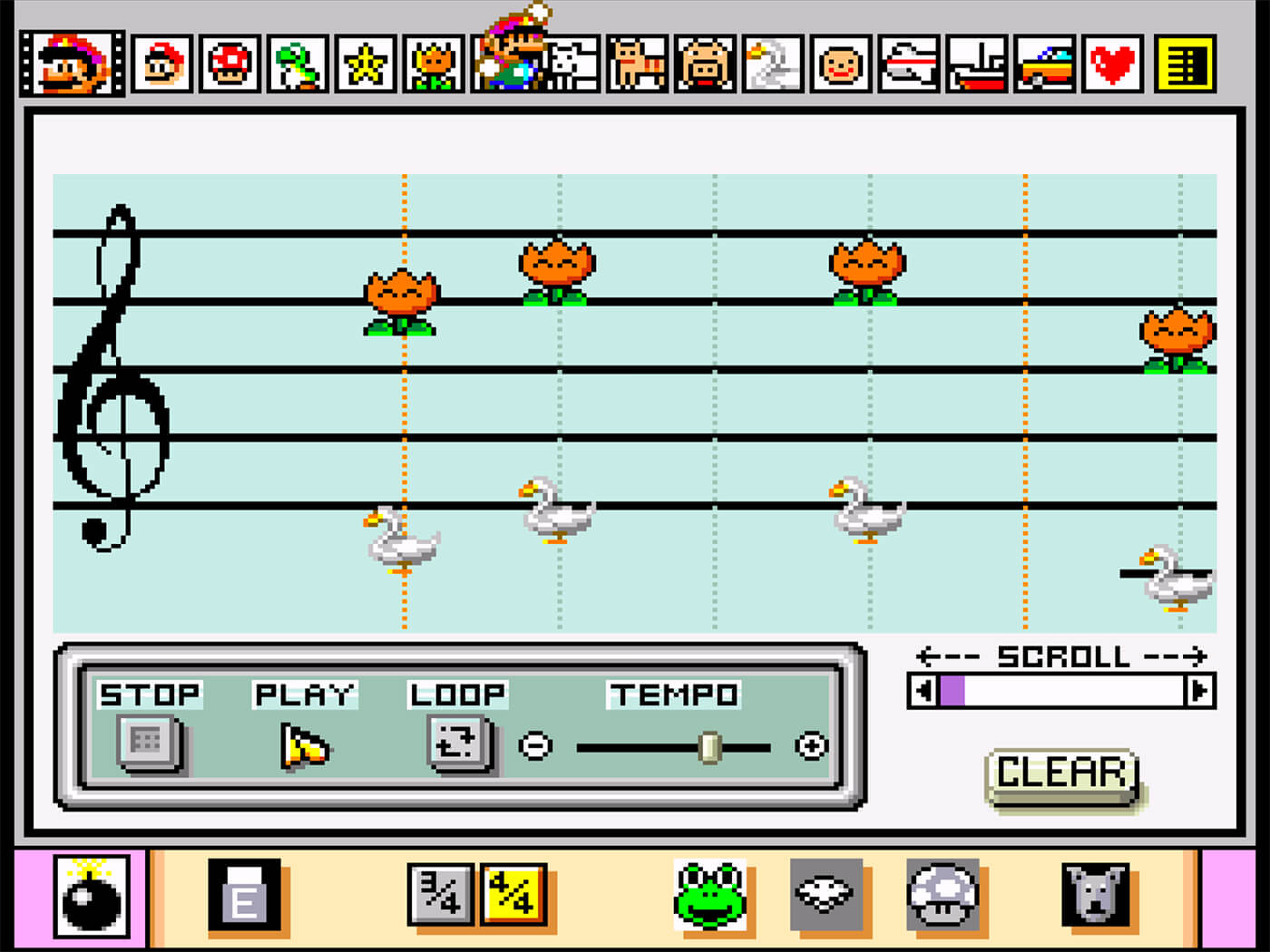

Nintendo Mario Paint (1992)

I don’t know how many hours I spent using Mario Paint to create horrifically low-tech video titles, but it was absolutely worth it. This was a SNES cartridge bundled with a nasty plastic mouse mat and a mouse that connected to the console – to use it was a matter of painstakingly drawing illustrations and little rubber-stamp-type animations.

It included a funky icon-based music interface, where you could create short phrases and beats with archetypal Nintendo-style sounds. I still have the samples from Mario Paint in my Ableton Live library – they’re quite easy to find online. You’ll also find Mario Paint ROMs online to play with emulator software, if you want the fuller Mario experience…

Elektron SidStation (1999)

Long after the Commodore C64 bit the dust, some Swedish folks built a synthesiser around the SID chip – this was Elektron’s first product, the SidStation. With only a finite number of SID chips available at the time, the SidStation has become something of a limited edition (bonus points if you own the even more limited black Ninja Edition).

The SidStation was challenging because of (a) the high price, and (b) the user interface, which consisted of a tiny LCD display, a numerical keypad, and five knobs. Sonically, though, it’s a lively animal, with arpeggiators, a filter and a lot of noise. It’s capable of producing smoother sounds, but few bought it for that! The SidStation sound outlived the hardware – first as an emulation in Elektron’s Monomachine synthesiser, then more recently as samples for its Octatrack sampler.

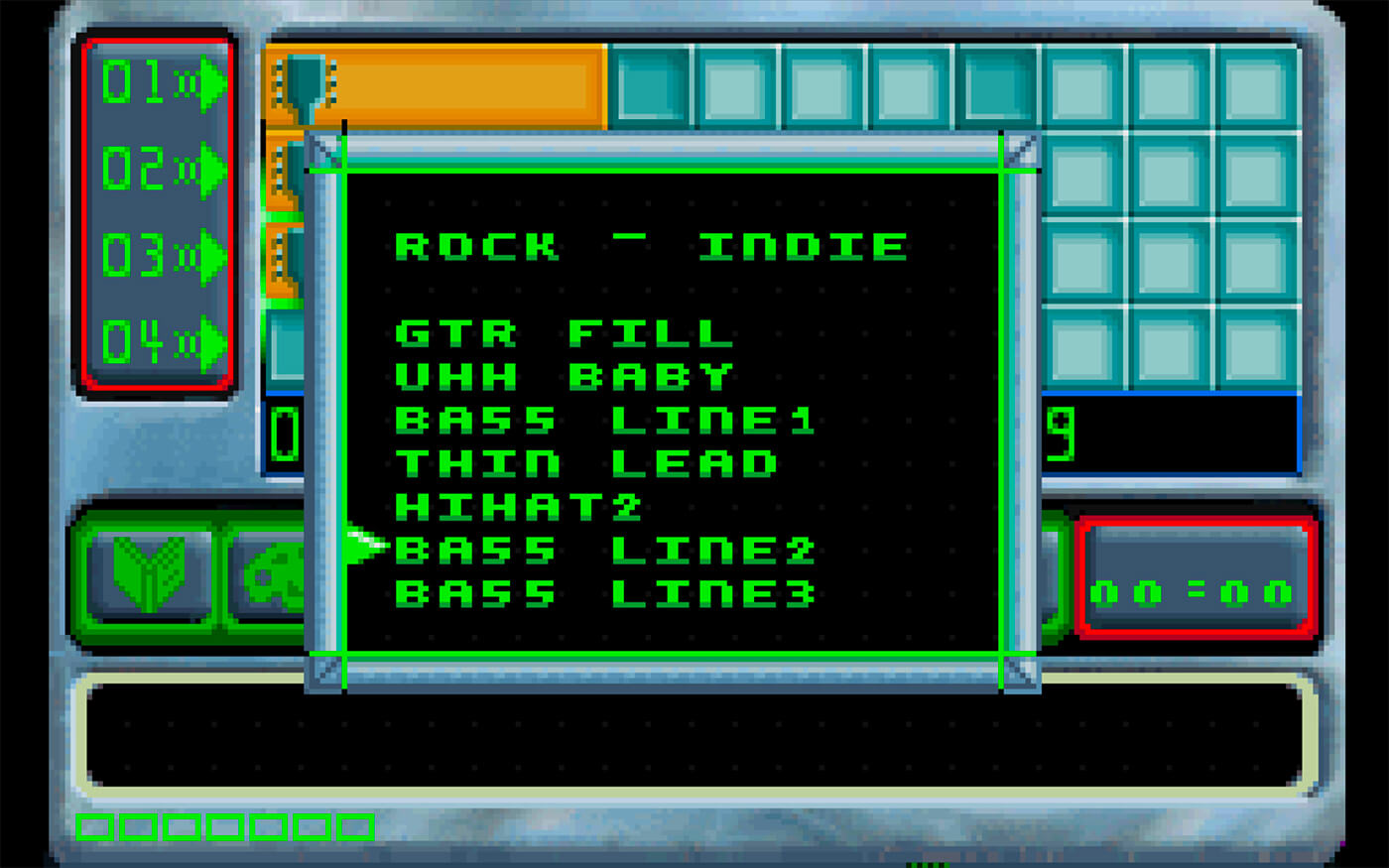

Music 2000 (1999)

Not so much a game as a music-production tool, which ran on Sony’s first PlayStation – the iconic console that brought gaming to the mainstream – this sequencer came with a library of ready-to-go samples and riffs. It was employed as the workstation of choice for early generations of hip-hop, jungle, dubstep and grime creators, creatively overcoming memory limitations to get their finished beats out onto cassette or CD.

It was also released in the USA as MTV Music Generator, and subsequently as Pocket Music on Game Boy Advance, although you’d have to be exceptionally dedicated to work with it on that platform. Check out the many Music 2000 videos on YouTube to develop a better appreciation of this limited but influential application, including original music, and covers of songs and TV/film themes.

Electroplankton (2005)

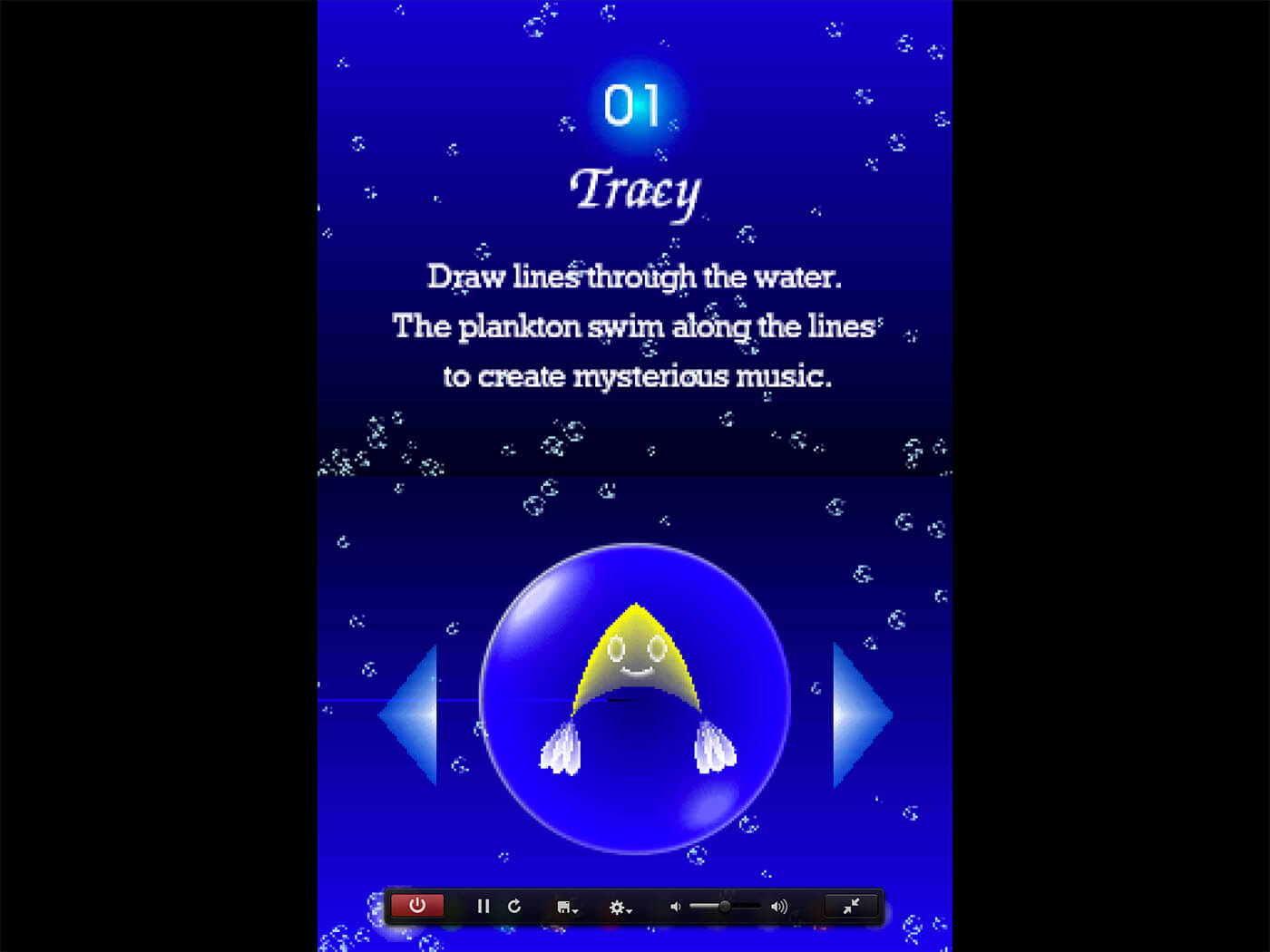

Electroplankton was a Nintendo DS product that effectively vandalised the barriers between game, music, and visual art. Select one of 10 colourful little plankton creatures, with names like Tracy, Luminaria, and Nanocarp, then draw a path across the screen and the software plays a musical sequence to accompany the route. The idea was to keep adding more of the little critters until, well, until you’d had enough!

You could record into it with the DS onboard mic, but there was no way to save what you created, so everything disappeared when you shut it down. Kind of relaxing, kind of musical, and also with an Audience mode, so you could just watch Tracy and the gang do their thing. It was designed by Toshio Iwai, who designed the Yamaha Tenori-On while also finding time to collaborate with Ryuichi Sakamoto.

Inspecting gadget

Korg’s Gadget is the ultimate example of take-it-anywhere production software, running on macOS, iOS, and now on Nintendo’s Switch console, with an intriguing multiplayer mode for up to four players. It’ll be even more impressive if they can get it to run on Android and Windows as well. The most valuable part of this portability is that projects are interchangeable between all platforms, although it’s worth remembering that projects originated on Switch can be moved from the console, but not back to it.

The icing on the cake is that Gadget productions can be exported as Ableton Live projects for completion in a fuller DAW setting, but even sweeter is that installation of Gadget for macOS also installs each of the 30+ Gadget instruments as a separate plug-in, which will run inside any DAW. This also ties in with the Ableton export, as it’s no longer required to render all Gadget parts to audio clips for compatibility purposes.

Nintendo Wii remote control (2006)

Sound is just one part of the game crossover. A key element of the Wii user experience was the Wii Remote – you know, that little white stick you spent hours waving about to simulate a golf club or whatever. You didn’t have to buy the console; the ‘Wiimote’ was freely available as an accessory. All you needed was a paired computer, and software to translate the remote’s messages to MIDI. I use OSCulator (osculator.net) for this – the buttons, joystick, and even the X/Y/Z orientation of the remote can be configured to send MIDI, making a powerful and cheap gesture-based wireless controller. The Wii is discontinued, but there are still plenty of remotes on eBay.

Yamaha Tenori-On (2007)

Not entirely leaving Nintendo behind, we come to the Tenori-On. You’ve probably seen it in movies or on TV, and it’s often made fun of as being super geeky, but it’s loved by many who have actually used it. This was a very adventurous product from a mainstream company, which we should applaud for taking a shot on it.

The Nintendo connection comes from Toshio Iwai, who we mentioned earlier in relation to Electroplankton. This machine is not to be underestimated – the lazy assumption is that it sounds weedy, but that’s down to the little onboard speakers – it might’ve been taken more seriously without those, because once you hook it up to a mixer, it sounds really great.

Gadgets galore

Korg’s Gadget is the state-of-the-art iOS music app in a mainstream sense, and a lot of that is due to it running on macOS as well as iOS. It now runs on Nintendo’s Switch, too, with a multiplayer mode for up to four people. Projects are interchangeable between the platforms, although to get them off Switch, a QR Code is used to send song data to the iOS version.

Gaming is also represented with the Gadget instruments themselves, with Kingston, an 8-bit style ‘chip synthesiser’, and Kamata, a wavetable synth based on licensed classic NAMCO sounds. Gadget sets the standard for multi-platform music apps with a game-like vibe.

The crossover continues, as interface designers try to create the next big thing. The Sub Pac S2 is a seat back that transmits low frequencies through your body. For the live performer, it’s also available as the M2X wearable model! (subpac.com). There’s an iOS synth called Shapesynth, which works as a self-contained instrument, or can connect to the popular Sphero robot toy and assign the robot’s accelerometer to synth parameters. We doubt this’ll be a major music-creation tool, but if somebody built an app that could connect the Sphero to other music apps, that could be very interesting.

The Myo armband connects to a computer via Bluetooth for control of software parameters, based on gestures but also muscle tension, which can make for some dramatic flexing and straining and a more physical performance. With an expert user, these become truly expressive music-input devices.

Korg DS-10 (2008)

Also on the DS was this Korg M-series-style virtual analogue synth, with two oscillators, and a drum machine. This actually had a decent set of controls, including pitch, portamento, waveform selection, filter, ADSR, and drive, with notes generated either by a sequencer, a keyboard, or a Kaoss pad X/Y interface.

The DS-10 used the DS dual screens pretty well, and it felt like a real attempt to get a synth on a handheld. Korg have been very forward-thinking in embracing new platforms and this must be seen as a predecessor to their success on iOS, where this lives on as an app called iDS-10. However, you’d be better off with Korg’s newer music apps, such as Gadget.

Microsoft Kinect (2012)

Following on from the Wii’s gesture capability, there’s the Kinect, which was originally a motion sensing add-on for Xbox, then later for computers running Windows. There’s an application called Synapse which runs on Mac and Windows, and enables the Kinect to control Ableton Live and Max/MSP, among other things. The website includes example Ableton Live/Max For Live material to get you started.

Note that there are a few cautions about using the correct version of the Kinect hardware, so make sure you read that before investing.

MIDI Fighter 3D (2012)

Arguably, the king of game/arcade-style music control is one built specifically for the job – the MIDI Fighter range from DJ TechTools. The MIDI Fighter 3D features 16 arcade buttons, four bank buttons, and six side-mounted assignable buttons. Each of the arcade buttons has a ring LED around it, and everything can be edited and assigned using dedicated editing software. It also includes a gyroscope and accelerometer, so any orientation parameter can be assigned to a MIDI function. Use it to launch loops, play beats, whatever you need.

The MIDI Fighter Twister replaces the 16 buttons with knobs that also double as push-buttons, doing away with the 3D features at the same time. Finally, there’s the monster of the range, the MIDI Fighter 64, which… well, yes, it has 64 buttons! These are impressive and durable boxes that will survive your tour with ease.

The present

In 2019, the relationship between gaming culture and music-technology culture is as strong as ever, as generations of gamers bring their influences into their designs for music products. I’d contend that working in Ableton Live’s Session View can be very game-like, and the effect is intensified if you’re using hardware control – whether it’s a game controller as we mentioned earlier, or Ableton’s own Push, with its 8×8 grid of chunky backlit pads.

Live also integrates with Max For Live, and that’s what is usually behind the more out-there Live content, such as Mark Towers’ LEGO Mindstorms project– little robots that can control Live in various ways, based on proximity of objects, waveforms made from LEGO bricks, a Whac-A-Mole-type game that generates chords, and others. Mr Towers also lovingly created Isotonik’s Arcade Series Ultimate suite of Max For Live sequencers based on classic arcade games.

Ready, player one?

You may never play games, but it’d be a mistake to overlook what gaming can bring to music production and performance. Due to its massive popularity, the gaming industry is at the forefront of tech developments – VR, multiplayers, Surround – all of which contain elements that we stand to learn and benefit from as music makers. Not everybody has time to actively study all of the new tech, but luckily, there are enough clued-in developers and users who spread the word when something exciting comes along…