Leo Abrahams on chance-based writing and successful collaboration in the studio

Sensorial, textured production is a hallmark of Leo Abrahams’ approach. Across collaborations with innovators such as Brian Eno and David Holmes to his co-written film-soundtrack work, through to the records he’s produced for the likes of Editors, Ghostpoet and Regina Spektor, Leo is creatively driven by a hunger to experiment and discover new sounds…

Leo Abrahams at his desk at Coronet Street Studios ready for a day of work. All this lay hidden below a nondescript piano store in Hoxton

From a young age, Leo Abrahams has lived and breathed the joy of music-making. He has channelled this passion into a prolific yet unpredictable career and has worked as a producer, collaborator, composer and solo artist in his own right. His behind-the-desk work has seen him sculpt records alongside the likes of Regina Spektor, Editors, David Holmes, Frightened Rabbit and David Byrne as well as the legendary Brian Eno, who – as Leo reveals in our conversation – first encountered Abrahams in a fittingly random way.

Leo’s own compositions, collected across nine solo albums, are layered and textured behemoths of sound, with his distinctively emotive guitar playing often to the fore. Leo is happy to traverse a variety of studios depending on the needs of a particular artist, yet tends to work from both his home studio and Coronet Street Studios in Hoxton, located (almost secretly) beneath a piano store. Which is where we meet Leo…

So how did your interest in music-making first begin?

I got obsessed with the record player when I was three. I used to put the same records on over and over again, which must have driven my parents mad. I think that’s when they realised I had a bit of a thing for music. After that, when I was around six or seven, I would sit on the edge of the carpet and pretend to play the fringe of the carpet as if it were a piano. Just trying to give them a hint that maybe they should buy me one!

I studied for a year at the Royal Academy of Music in the hopes of becoming a classical composer, but I soon became disillusioned with that course and took up a role as touring guitarist in Imogen Heap’s band. That was for her first album, in the early days of her career, so we’d end up playing in pubs to tiny crowds, or sometimes no people at all. But it was enough to make me realise that that was probably the way I wanted to go.

So at what point did you diverge into the production world?

There’s different strands to it. I went to school with Jon Hopkins and he and I were in Imogen’s band together, and then we started working for various songwriters and producers just as session guys.

Imogen took me one night to a club called The Kashmir Klub, there was a sort of open-mic night there. A lot of people who went on to be quite big started out there. Ed Harcourt was playing that evening and at that point, he was unsigned. I really loved what I heard from Ed, so I just went up to him and said: “Do you need a guitar player?”. He invited me to meet him the next day for an interview. We met on Kensington High Street and his first and only question was: “Do you like Marc Ribot?”, to which I answered: “Yes!”. And then he just said: “Okay, first rehearsal is tomorrow.”

So once I started working with Ed, I started doing string arranging for both him and other people on his label. I did some string arranging for Starsailor. I think because I’d been to music college, people just believed that it would be alright for me to take on that job.

In my early 20s, I caught the very end of the period where record labels would invest and support bands financially; I was really lucky to see that. So even though I wasn’t a producer at that stage, if it hadn’t been for the retainer that I was on with Ed Harcourt for three years I might have had to get another job. But luckily, that saw me through. Once that era had passed, I had enough contacts and work lined up that I could make enough to get by.

Leave it up to chance

So meeting (and working with) Brian Eno must have been quite an astonishing experience, how did you initially contact this legendary figure?

Well, It was an outrageous stroke of luck. I was in a Notting Hill guitar shop – testing the intonation of a guitar I was interested in. I wasn’t playing anything flash at all. Brian was in the same shop and heard what I was playing. He just came over and told me that he thought what I was playing was “tasteful” and invited me to his studio to work on his album Drawn From Life.

Brian ended up influencing my career a lot, as did David Holmes (with whom Leo worked on the record The Holy Pictures) they are both incredibly honest and generous people. Looking back there was no reason for them to be as generous to me as they were. I guess the industry standard was to pay their assistants a small day rate but if I’d composed something with Brian or David, then they had no hesitation in giving me a writing credit. They were just very, very kind and it literally changed my life. It wasn’t like I could retire or something, but it made life a lot easier and enabled me to focus on music. It also allowed me to be more discerning (or you could say, spoilt) in that I never took any work that I didn’t want to do musically.

What inspires you when you compose and is there a typical starting point for your process?

Well, I don’t really consider myself a composer anymore. I did make a bunch of my own solo records, but at a certain point, I guess I stopped liking what I was naturally coming up with. A few years ago I made a record called Daylight, which was based on chance, and the fundamental building blocks of the songs were random. I don’t think that’s an entirely uncommon way to work. I set up systems that I couldn’t really control and then orchestrate them so I was using more of my ‘editing brain’ and relaxing my ‘composer brain’.

I would orchestrate in quite a detailed way these pieces of music that were generated from chance. They ended up feeling like they’d been composed. I wouldn’t just edit them together, but I’d build so much on top of these foundations that I’d eventually often take away the original chance-built element from the mix.

Was that method inspired by Eno?

Part of it was actually Frank Zappa, who I was really into as a kid. He’d often take some live guitar solo that had been recorded at one concert and combine it with a rhythm section recording from another concert. Then get a whole brass section to play the guitar solo and then take the guitar solo away. So you were left with this artefact that no-one would write from scratch. It was totally original. I like the feeling of discipline and wildness at the same time.

The other thing that influenced me a lot was the classical composer Morton Feldman. He was very concerned with repetition and imperfect symmetry. I became interested in this idea of things that never repeat exactly the same. It’s more than just putting an LFO on something to make it slightly different, what I mean is purposefully composing the thing with differences.

A different kind of fun

You’re a frequent collaborator and arranger – when working with other people on projects, do you speak to the artist about the shape and structure of the tracks or do you plan arrangements by yourself?

I think my favourite aspect of the job is that every band or artist needs something slightly different and so when we’re first meeting, I ask them why they’re not self-producing. There’s usually a specific aspect of the process which they want help with and I just focus on achieving that. Sometimes people want me to play, sometimes they want me to arrange and sometimes they just want me to help them through the process in a supportive way.

I think whatever you do as a producer the end result will come out with a certain ‘hallmark’ of yours. But I don’t have ‘a sound’ that I seek to filter the people who come and work with me through. I’d much rather chase down their sound. I prefer the artist to do as much as possible and for each record to be as distilled a manifestation of their personality as it can possibly be.

Is it a ‘sat side by side’ kind of collaboration that you prefer?

Again, it varies, but in tracking there’s usually a lot of tidying up and technical stuff to do and most artists like to have a bit of a break, so I’ll usually edit on my own. Once they come back they’ve got fresh ears and they can help me if they hear something that I haven’t noticed. In my experience, a lot of artists start out wanting to attend each stage of the production process, but in the end they come to appreciate that stepping away can result in a more refined end result.

You’ve done a great deal of varied things in your career to date – what do you enjoy doing most of all, writing music, arranging, playing, soundtracking?

I really love producing, it’s all-consuming and very satisfying but I think the more production I’ve done over the years, the more I realise that I actually really enjoy just playing guitar on sessions for other people. It’s a bit less existential for me – I can turn up at a session and treat it as a job, but in a very serious way. I also find it really fun and really interesting to step into other people’s worlds just for that small window of time. But when the session is over – it’s over! With production, it’s all-involving. That’s one reason why I try not to take on too many projects. There always seems to be time pressure and there always seems to be the chance to make something you’ve never made before hopefully. Someone’s trusting you with their baby, really.

I’ve worked on a fair few soundtracks and the pressure the guys who are leading those projects are under is immense, but my role is more as a session player for those. Working on an indie record can often be quite a solitary experience. It’s a very significant responsibility that extends over a long period of time. With guitar, my responsibility is around three hours long. It’s a different kind of fun.

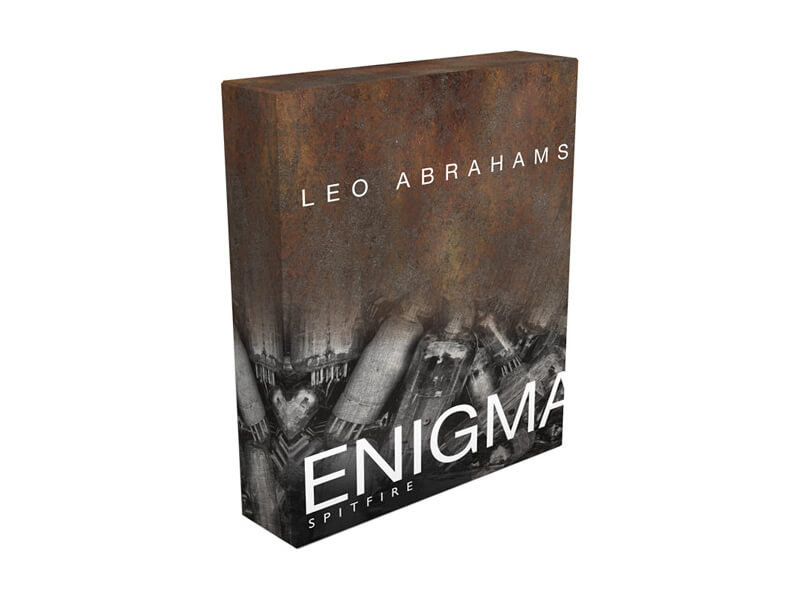

Building an enigma

You’ve worked with Spitfire Audio in the past. How dId that come about and what was the process of building a sample collection like?

I came on board very early for that. I do sessions for Christian Henson (Spitfire co-founder); after one session he took me for a beer and told me he was starting a new company and asked whether I’d be interested in doing a library of sounds. At that time, I was just about to update my operating system, which would mean I’d have to leave behind all these channel strips that I’d made for various reasons. I thought this was probably a good way to say goodbye to them and move on. That’s what I did – that was Enigma. I recorded all of that at my house in my home studio. For the second one, we went to The Pool and I made all the sounds on the spot from scratch.

The third volume we’ve made, I created from scratch at the Spitfire studios. I didn’t have anything pre-prepared. I’m really happy that people seem to be using them a lot, I’ve had some nice comments about it. I think it works because it’s in an ambiguous space – it doesn’t sound like keyboards and it doesn’t sound like guitars.

What’s the most important thing you’ve learned in the studio?

I think it’s the importance of being able to shift perspective a lot, and quickly. Going from real detail to big picture – it sounds quite obvious, but it’s not that easy. One of the most important things a producer can offer an artist is perspective and hopefully, experience. Particularly if you’re doing a lot of programming or fine editing, it’s really easy to lose perspective on the project as a whole.

Also, to feel that if you’ve worked on something for two days that it may not be quite right. You only get one chance to do these things and so it’s really important to be honest with yourself and stay connected to the creative discussion you had at the start of the process. That’s not to say that you can’t get diverted on the way and have fun and explore. But don’t lose sight of that first instinct to create. It’s in the artist – you have to stay close to the artist and realise their vision.

How does the writing process for one of your own records differ than working with another artist and do you have a vision of the record before you start?

I don’t really want to make any more solo records unless they’re born out of improvisation. I prefer to take things that are more or less complete and finishing them off. Quite often, people will come in and their tracks will be around 75 per cent finished and I really enjoy helping them with the last 25 per cent. Again, I think it’s a perspective thing and also not being invested in the writing process. You’re building what’s required of the song and you can almost write to fit that brief.

A diverse ecology

When you were making your own tracks, did you structure those creative sessions and did you impose limitations on yourself?

When making my own stuff, I would often get a feeling of the essence of the thing that I wanted to make and I would always try and stay close to that. Beyond that, I’d try and use any time that I wasn’t busy to do my own stuff. There always comes a point when the end is in sight and you can start making to-do lists and stuff. But before that, I like it to be open.

What does motivate me, though, is the fact that I really like finishing things! I’m not a big one for letting things go – I think that’s a good thing. What is quite nice is when bands get in touch with me wanting to work with me they often reference my records and not the things I produce for other people. That’s really rewarding, actually.

Is there any project in particular you’re proud of?

There’s an album by David Holmes called The Holy Pictures which we worked on really closely together. For me, that just encapsulates a time that I’m really fond of. I’m also really proud of the record I made with Regina Spektor, Remember Us To Life, because again, it was just a beautiful time and she’s such a warm and bright person. I really feel like that record captured a sense of who she is. So probably those two.

I’m quite hard on myself about the work. I really don’t very often listen to what I’ve done. If I do, then I’m more prone to hear the faults in it. I worked with Frightened Rabbit (whose frontman Scott Hutchison sadly passed away in 2018) and as a way of dealing with what happened with Scott, I played the record we’d done together, Pedestrian Verse, and I was quite moved by it, and actually didn’t hear anything that I would have changed. I realised that it was a great record and I knew that he was happy with it. It’s ultimately more important to me that the artist is happy with it, because I’m never going to be happy with it!

When an artist talks about the record in an interview and says they’re happy with the end result, then that really means a lot to me. When you hear other people’s work there’s always such mystery about it and I think it’s often easier to see beauty and perfection in other people’s work.

What advice would you give to anyone looking to have a career like yours?

Well, if it was specifically like mine – which is quite all over the place, really – then it would be to not have too set ideas on exactly where you want to end up. Just do everything that comes your way that feels right. And only the things that feel right. That’s it, really. I don’t mean to sound disingenuous, but I’ve never actually tried to have a career. I’ve done a lot of things that might appear to some to be odd choices or maybe not very cool. But I wanted to do them – I had my reasons.

I’m really happy to be in this diverse ecology of musicians. One day, I’m working with a very commercial singer and the day after, I’m working with an avant-garde performance-art cellist. That’s kind of the reason I got into music – to experience a range of different things.

There’s so much luck involved with making music. I always think the best thing you can hope for is to have a lucky break and then not balls it up! But you have to be open enough to recognise those signs when they come.

For more of Leo, check out his official website here.