“I can’t get any satisfaction from pop music today”: producer Michael Beinhorn

Although responsible for a string of iconic 90s rock records, the Grammy-winning producer is venturing into the nebulous field of pre-production. We discuss physical reactions to music, why hooks aren’t always good, and the unenviable task of being the bad guy.

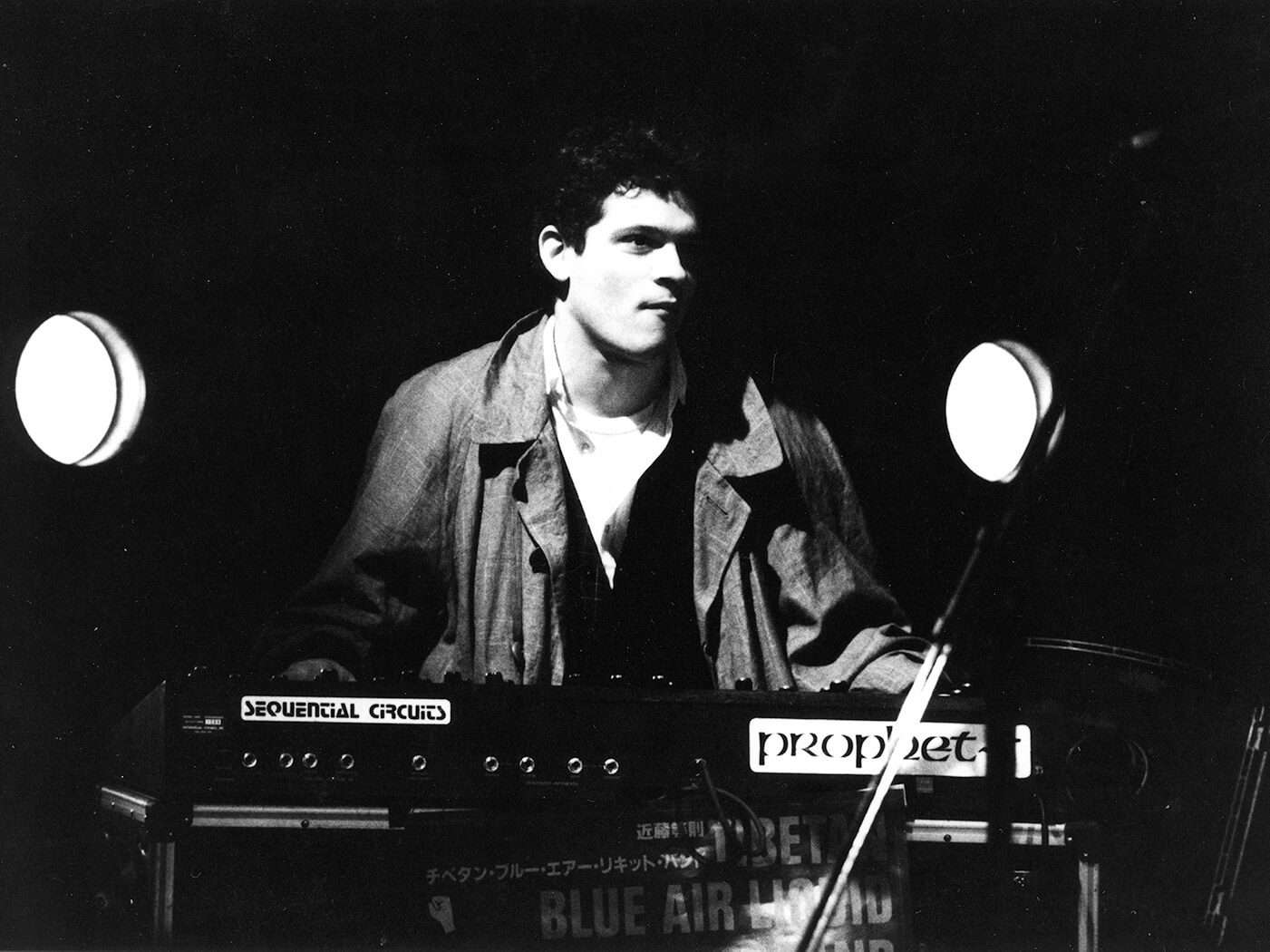

Michael Beinhorn got his big break in production working with Herbie Hancock as a synth and drum programmer, co-writing the breakdance favourite Rockit. However, he’s best known for his work on 90s rock records such as Soundgarden’s Superunknown, Marilyn Manson’s Mechanical Animals and the notoriously troubled recording of Celebrity Skin by Hole. Now he’s drawing upon his wealth of song-crafting experience to work in the world of pre-production.

Pre-producer

The term pre-production can have wildly different meanings, depending on who you’re talking to. For Michael Beinhorn, the fundamentals are simple: “I think pre-production is the cornerstone on which a really great recording is going to be built,” he says. “It encompasses all the preparatory work that addresses the structure of a recording. In terms of all the music, arrangements and song composition. And it can go as far as dealing with interpersonal aspects of the recording.

“That’s to say, individuals who are struggling with parts or the internal dynamics between people in a band. There might be certain blocks that are causing the artists to be incapable of delivering their best work, and in pre-production, we find ways to get around those.”

That may seem like a broad remit and Michael is the first to admit this. “It’s an all-encompassing umbrella term that can cover a lot. It’s going to vary depending on the project, the artist, what the needs are of both, and what kind of music it is. So it has to be very flexible and freeform.”

The process differs if you’re not also the person behind the glass when it comes time to produce the record, as Beinhorn explains: “Producing a record from top to bottom involves a different kind of investment, because I also have to envision an overall sonic presentation for them. What is this going to sound like? What is it going to say? What’s the meaning behind it? How does that look? What kind of equipment does that? What kind of recording process reflects this?”

Beinhorn’s role with pre-production is to shepherd the process right up to the point when the artist or band enters the studio. This means making sure all the parts, lyrics, melodies and song structures are complete. Or as he puts it: “Everyone knows what they’re doing, and their performances are going to be okay.” This can also involve attending rehearsals, where necessary, to help the band nail their parts.

Listening with your gut

The role of the pre-producer, in Beinhorn’s eyes, is to bring a fresh perspective to songs that the artist might have become too close to. The process begins with listening. “I think you have to start out being a good listener – that’s the process of listening as opposed to hearing. To me, I always see hearing as passive and listening as active because you’re conscious of the act.

“One of the best things I think I can bring is just having an intuitive sense of what feels right or what feels iffy,” says Beinhorn. And, while he admits that part of this is personal opinion, he maintains that it’s also more primal than that. At least in the first instance.

“It’s not necessarily a cerebral thing. In fact, I would say that if it is cerebral, then you might not be listening to the music in the right fashion,” Beinhorn says. For him, listening in the right fashion is about getting a visceral, gut sense from listening to the music. And this goes equally for elements that are sitting well as those elements that are sitting poorly. According to Beinhorn: “It all starts from a sensory place where you have an understanding of what doesn’t feel right.”

Magnetic repulsion

Beinhorn admits that this process is on the more esoteric side of record production. Regardless, there are concrete ways that you can judge whether a piece of music is working or not. It’s not just a case of waiting for the hairs on the back of your neck to stand up. In fact, it’s verging on mindfulness. “For me, I’ve become aware [when listening to music] of where in my body I feel something. Or whether I’m feeling anything at all. What might that be and what do I relate it to?”

For example, he says, “there can be the experience of listening to music and being repulsed by it, physically.” For the veteran producer, that means he just has to hit stop on whatever is playing. “That’s a useful point of information if that’s the sensory reaction,” he says, suggesting that when you feel a sense of revulsion, you’re barking up the wrong tree.

Wandering minds

There’s another, less extreme, point of reference that he mentions, and we’ve all experienced it. “I find that if my attention starts to wander at any point, I know that I’ve hit a null point in a song.”

Once he’s listened through everything, he returns to those “null points” to analyse the reason for his attention wandering. “It may come down to the fact that the song just isn’t that good,” he says, half-jokingly.

“Understanding structural aspects of it is very important,” he says. Once finished with the sensory phase of listening, he says he can then pinpoint structure, because “if I know where something’s wrong, I can use my brain to help me figure out why”.

“In a lot of cases, you can pinpoint it to something basic, for example like the way a bass-drum pattern may not be supporting a vocal, the way the root note may be working against chord parts. It could be a certain inversion of a chord,” he suggests.

“There are all these little details that, individually, may be very small, but cumulatively, they affect the flow of the song and they cause a person listening to waver in their attention.”

Once he’s identified the musical or structural causes of the null points, he’s armed for a conversation with the artist.

Forensic science

What Beinhorn finds most fascinating about this part of the process is how the artist can move from a position of subjectivity to objectivity, becoming able to see the flaws in their work. “They’re able to look at it forensically and analytically. They can see where the problems lie and hear input, critical or otherwise, that may be helpful to them getting their songs in a better place.”

He attributes this change in perspective to the artist being able to separate themselves from the work. This can be incredibly difficult, especially when the songs are an expression of an artist’s experiences. And a producer has to be careful that this type of critique isn’t interpreted as a personal attack.

A recent example of this approach was when Beinhorn was brought in during pre-production of Weezer’s most recent self-titled record, known as ‘The Black Album’. “My involvement was basically doing pre- and post-production on a bunch of songs. This came down to me giving some unvarnished critique on some tracks. Maybe I should use the semi-glossed version of unvarnished,” Beinhorn jokes, “because if you come in with that kind of feedback, you’re invariably like a bull in a china shop.

“What I discussed with [Rivers Cuomo, lead singer of Weezer], was issues with structure and lyrics. When you’re presenting someone with information like this – especially someone who’s had a very long, successful career – there definitely will need to be a degree of diplomacy involved. But, I was as honest as I could be. Obviously, [any critique] has to be presented in a way where it’s not chiding, it’s very matter-of-fact,” he explains.

Lessons for artists

As music-makers will know, objectively analysing your own musical creations can be very difficult. Can any of these ideas be applied to examining your own creative work? “It’s important,” Beinhorn says, “but it’s almost impossible for a person to do that themselves. Therefore, if I was going to make a record of my own music, I would probably hire a producer, someone whom I trust, because I don’t think just anyone is really up to the task.”

Whether you’re a self-producing musician or producing an artist, some common problems can be rectified in pre-production. One is the arrangement. “I notice with shocking regularity that people tend not to listen to how drum parts work with vocal lines. When you’re dealing with a band, a lot of times, people are focused on their own parts.

“It’s very easy to experience a divide when people aren’t listening to the effect of what they’re doing on the other instruments and the entire piece of music. So you’ll find that in some cases, there can actually be straight-up cacophony, which is fascinating.”

In one case, this was for a very particular reason. “I actually got a recording from someone. This person is a really talented musician, self-taught as well. The songs are very complex, everything’s playing at the same time. It’s like a sea of instruments. And I said to him: “It’s as if all the people on your recording aren’t listening to one another.”

The cause was remarkably simple. The artist replied: “‘That’s really strange, because it’s basically all me.’ I had never experienced anything like this in my life. It was quite a revelation. When I listened back, I thought, ‘Yeah, I can see how this could be the same mind at work.’”

Vocal native

An easy rule of thumb for avoiding the “sea of instruments” phenomenon is to understand the function of the instrumentation in a track. Beinhorn explains: “In any composed music where it has a lead instrument (and in the case of Western music, it’s always going to be a singer), everything else around the vocal is window dressing.

“It doesn’t say anything less about great players like John Bonham either, because people still care about his drumming even though he’s there to support the vocalist. But without the vocalist, there’s no song. People don’t listen to Whole Lotta Love for the three-minute drum break,” he says.

It’s not just about what the parts are playing and setting levels. “If anything else is standing out more than the vocals – like if you listen to a guitar player and when the vocal comes in, everything goes flat – then you’ve got serious issues.

“The problem there could either be emotional or systemic. If it’s emotional for the singer, because they are withholding, as the producer it’s up to you to remedy that. And if you can’t do it, at least you tried. If it does work, and you’re able to get something amazing out of them, great. The other alternative is that the problem is, in fact, systemic, which means there isn’t a whole lot you can do other than saying: ‘You’ve got the wrong vocalist in your band’.”

Fire in the hole

Over his career in production, Beinhorn famously gained a reputation for dismissing band members, particularly if their performances didn’t pass muster. According to his own recent account in a Produce Like A Pro interview with Warren Huart, Beinhorn kicked singer Anthony Kiedis out of the Red Hot Chili Peppers during the recording of the 1987 album, The Uplift Mofo Party Plan. He also famously dismissed drummer Patty Schemel from the recording of Hole’s Celebrity Skin recording sessions. In spite of the resulting falling out between Schemel and the rest of Courtney Love’s band, Beinhorn is remarkably sanguine about the sequence of events.

As he recollects, he was hired to produce the album on the condition that he did not fire the drummer, Schemel. However, when her performance in the studio did not meet the standards of the rest of the band, he asserts that he was called upon to fire her.

He explains: “It was left up to me, but they made a good point, which was that they had to deal with her. They still needed to be in a band with her, and they don’t want this to affect their relationship with her.”

As Beinhorn sees it, “it had to be done despite any misgivings because my job wasn’t to make friends with these people. My job was to produce their record and be a producer. And part of that is to deliver bad news.”

“You have to ask: ‘What’s holding us up here? And how do we circumvent that?’”

High ground

Having worked with notoriously difficult figures in the music industry, Beinhorn promotes a calm approach when tensions run high in the studio.

“My role on the project is to serve whatever the process of getting to the end result happens to be. I serve that, and that’s it. Every person on the project has to be subjugate to it. If they don’t surrender to it, they’re gonna get consumed by it, or they’re gonna mess it up. It’s someone else’s music and life, and we have to respect that to the greatest extent that we can and represent it in the best way possible. So you have to ask: ‘What’s holding us up here? And how do we circumvent that?”

How does one get to that place, if you’re already personally and professionally invested in a project? Beinhorn suggests: “The first and the best thing to do, especially in a tense situation, is to take a step back and take a deep breath. Centre yourself and take yourself out of any drama that you might be in the midst of,” he suggests.

Once the problem has been identified, “that’s when the producer has to use any kind of psychological means at their disposal – not to manipulate the artist back into place – but to show through reason, we hope, how to get back to where we were before. When things were moving along at a nice clip.

“If there are insurmountable problems, what are they? And what needs to change to get them to be productive again? Having been on a couple of projects where we had to dismiss musicians is always a tough one. But you’ve got to deal with it and come up with a solution to the issue. Especially when that problem interferes with the directive of the artist – and what the artist wants and what they specify for their project.”

Tension and release

When asked what music he has listened to recently that really excited him, Beinhorn responds dryly: “That would have to be the Bach Cantata No. 140.” And, when pressed, he expands on his initial statement, citing Russian trap acts. It’s the more mainstream music he takes issue with.

“I can’t get any deep satisfaction from the kind of pop music that people are making,” he says. “Prior to this period in music composition, there had to be elements of tension and release that took place in a piece of music. To the extent where you get sucked in by something that caught your ear, but it wasn’t necessarily always hooky. It was something that made you want to go along with the arc, the movement of the song.

“A great example of this in my own work is Black Hole Sun [by Soundgarden] which is a song where if you listen to it, I would say there’s almost no release in the whole thing. It’s all tension, it’s all build-up. But you get so worked up by the whole thing, and it’s so otherworldly that you just want to go along and you don’t want to ask any questions,” he says.

“If you listen to a song that’s structured now, what you find is you have three sections. You have an A, B and C, all of which are hooks. And obviously, the climactic hook has to be the most powerful hook in the song. You have no tension.

“Something happens as a result of that which I feel is very unnatural to composed music, and that is that you’re constantly dealing with release. It causes the music to flatline. It doesn’t have the same dynamic arc, it doesn’t have the same kind of pulling power. It doesn’t have the same emotional magnetism that a piece of music should have to keep you engaged. And when you listen to music like this for a prolonged period, you get the feeling that you get when you’ve had too much sugar.

“Trying to sustain that level for too long in a piece of music, it goes against what music does. It’s actually asking too much of a listener, and I think that it really kind of detracts from the experience and the pleasure of listening to music.”

Expert advice

What is Michael Beinhorn’s advice for achieving a successful career in music production? He explains that there are two ways that producers can go: workmanlike or forging new paths.

The first looks to support and serve: “Discover every single formatted, approved, standardised approach to production at this particular point in time. Learn them all well and use them in service of people in the recording industry.”

He continues, “The other approach is to learn all those things and say: ‘I’m going to make records exactly the way I hear them in my head’.”

For a producer, says Beinhorn, stand out success comes from exerting your point of view on the music you are involved with. “That goes back to trusting your gut when you find projects and having a vision for what you can do after you’ve trusted your gut. When you have that, then you can wield some serious power.”

This way is not without difficulty and not everyone is ready to work with an innovator, but Beinhorn says, it is ultimately the path with the potential to create the greatest sense of professional achievement: “If you come in and you’re an innovator, and you have success with your innovation? Then they all want you. The road is harder that way, but ultimately, it’s much more satisfying.”

Read more about Michael Beinhorn’s work with Soundgarden and Hole.