Mandy Parnell Interview – A Master Of The Industry

One of the country’s foremost mastering engineers, Mandy Parnell has worked with artists such as Björk, Aphex Twin and The xx. MusicTech travelled to her Black Saloon Studios to talk about her award-winning career… The roster of artists who’ve brought their records to Black Saloon, Mandy Parnell’s quirky Walthamstow mastering studio, is seriously impressive, from […]

One of the country’s foremost mastering engineers, Mandy Parnell has worked with artists such as Björk, Aphex Twin and The xx. MusicTech travelled to her Black Saloon Studios to talk about her award-winning career…

The roster of artists who’ve brought their records to Black Saloon, Mandy Parnell’s quirky Walthamstow mastering studio, is seriously impressive, from Björk – whose Biophilia and Vulnicura were mastered by Parnell, to Aphex Twin’s stunning return, Syro. Parnell has been mastering for decades, training at the SAE Institute before learning her craft at The Exchange Mastering Studios.

Her work has been nominated for Grammy Awards and, in 2015, she won the MPG’s Mastering Engineer Of The Year gong. We spoke to Mandy about her life in mastering and the impressive vintage gear she has tucked away in Black Saloon…

MusicTech: How did your interest in music come about?

Mandy Parnell: “My parents had a café in Wickford in Essex. It was one of those classic greasy, English breakfast places. My parents would take me there and they had this amazing jukebox, every now and again, this guy would come round and change out the 7″ records in there.

“The records they took out they would sort of dump, in a sense, and occasionally, he’d give me these old 7″ records, so my parents bought me this really old record player. I can’t remember how many records I could stack on it, but pretty soon, I had loads of the chart stuff from the time: Wings, the Bay City Rollers and lots of quite cheesy pop from the early-to-mid 70s.

“Music played a big part in my life growing up, all the way through school (I actually went to a boarding school) I’d very often get my radio confiscated for listening to Radio Luxembourg. This led me to study music more academically, and I learned guitar and piano. I was very into music and went to gigs, concerts, etc.”

MT: When did you first think about starting a career in music production?

MP: “I had a friend called Julie who worked at The Manor, which was where Richard Branson’s residential studios were in Oxford. She invited me to come down for the weekend, just to hang out. So I did, and we had a great time, but just before I left, the assistant engineer said to me: ‘Do you want to see the studio?’. I said: ‘Sure,’ so I walked in there and it was like love at first sight.

“I came back to London and instantly looked at courses. There were three music-tech courses. This was SAE’s second year in the UK and I got on a course there and ended up being taught quite a lot about mastering. I remember while I was there having a demo of the very first AKAI sampler, so it was quite far back. Anyway, one night, I was on the phone to my best friend and I was jut flicking through the pages of an industry paper and I noticed an ad that was looking for trainee mastering engineers at The Exchange.”

“So I phoned up and the bloke there told me that they were shutting down applications the next day and I had under 24 hours to get a CV in. I didn’t really have a CV so I had to quickly get one made up. I didn’t have access to anything to type it, so I hand-wrote it on a white bit of paper. My handwriting wasn’t great and I’d scribbled out a load of mistakes – I don’t really know what planet I was on.

“But anyway, I got an interview on the strength of it. Many years later, my boss Graeme dug out that tatty old CV and showed me it, and told me that they got me in for a bit of a laugh, really. They set up the interview because they couldn’t believe that someone would actually send this CV in. One thing that was very clear in the interview was that they had an agenda to promote women in business (this was the Thatcher era) and that one of places was going to go to a woman, regardless of skill level.

“One thing that was pretty interesting, looking back on it, was that they were actually quite against getting people in who had formal qualifications, as they did their training in house. This was actually a fairly standard model for studios years ago. They would take people on and train them up to work to that particular studio’s ethos.

“The interview was pretty good, they asked me a lot of technical questions about reel-to-reel and analogue gear, which I knew inside out. After it was over, I called up about three times asking if there was any news. Eventually, Graeme from The Exchange called me up and told me they wanted to offer me the place. It was a paid position as well, which was something they were very clear about, they were very anti the work-for-nothing model that so many studios and creative industries use.”

MT: When did you launch the studio?

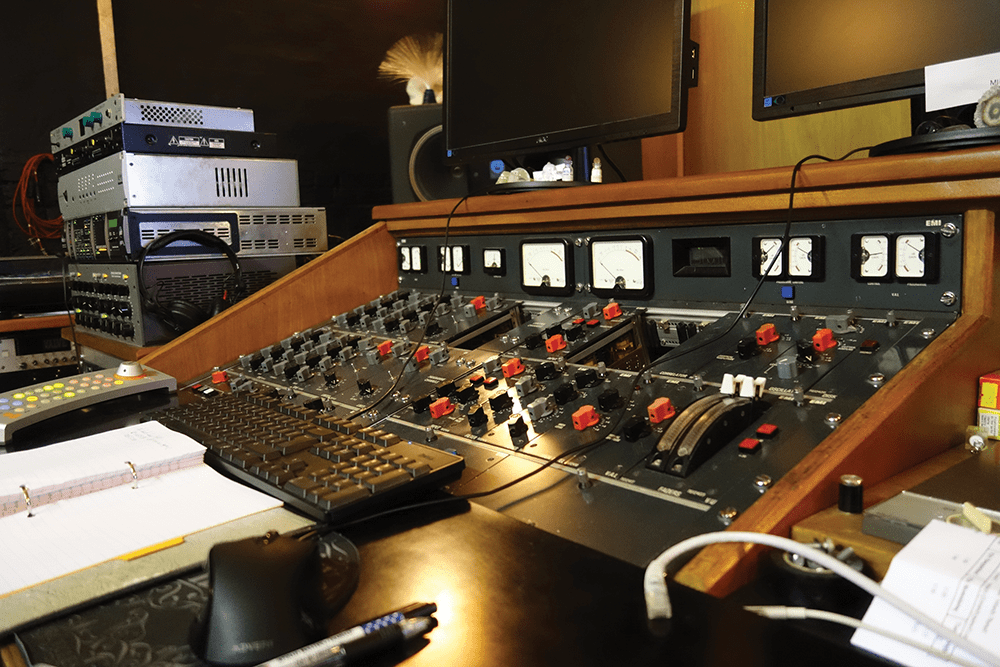

MP: “Around eight years ago, I can’t actually remember! I wouldn’t actually recommend to any of your readers that you set up your own studio, especially for commercial use, as there’s so much admin to do that gets in the way of being creative. It was a series of events… After I left The Exchange, I started collecting equipment and I bought some of The Exchange’s stuff: EAR compressor/limiters, which I’ve had my whole career. Graeme sold them to me. The stuff I used to use at The Exchange, like the dbx De-Esser and Valley De-Esser, I kind of wanted, too. It was a very analogue studio and I suppose I didn’t really understand much about digital audio. We’d been doing CD mastering for years, but on a technical level, none of us were über-geeky about it.”

“After I left the Exchange, I went back to SAE and re-did the course that I’d done previously many years earlier. My lecturer Rory asked: ‘Why are you here? You’ve already done this course!’ – but I wanted to learn about digital audio, as it was becoming more and more standard in the production world. During that time after I left The Exchange, the guy who ran Electric gave me a call and said he’d love me to come and work with him. So I did. He knew what my ethos was. I went over there and helped to re-set up the rooms. He had really nice equipment, like an EMI desk; he had different Prisms, but we got him to move up to the ADA-8s. We set the lathe up, so I worked there for a while and made some pretty great records. Records that got Grammy nominated and tech-awards nominated. I had a great time!

“While I was there, I started thinking about my future and maybe launching my own studio. It was my partner Martin who pointed out that they were all my clients that I was bringing to Electric; sure he had the equipment, but so did I, by that point. I had the EMI desk and a lathe, which I’d bought my son to teach him how to cut 7″s.”

MT: Where did you get the gear?

MP: “I got it from a guy called Sean Davies, who used to be Yes’s engineer, and then became a mastering engineer. He basically became our leading expert about vinyl. He used to repair all the lathes in the UK. He sourced the equipment for me. He’d been around my career from early on in The Exchange and luckily, I’d won his respect. When I was at Electric he came along and asked how I was getting on with the desk. I told him it was a revelation to have this desk, it was such a massive timesaver.

“He said that he had a friend who had another one in storage, as he’d moved his studio and the desk wouldn’t fit in to it. So he went to speak to him to see whether he was interested in selling it, so he called me up and said he’s interested, but that he wanted to meet and chat with me first. I drove over to his warehouse where he was doing plating on vinyl and this guy was one of the premier (pre CDJ) dub-plate cutters for DJs (so they could check the mixes on the dancefloor before they went to press).”

“So this guy was really cool and we hung out for a while. He pulled this sheet off it and there it was. There were no speakers or anything attached to it, though, so I couldn’t test it. Sean called me the next day and asked what I thought. I said: ‘Sean, I couldn’t test it so I can’t really tell!’ But Sean said: ‘If you want it, just trust me, it’ll be fine.’ He then came back to me with a deal I couldn’t resist. He was going to deliver it to my house in his van. But to buy something for such a large amount of money without checking it was really a leap of faith. Sean was away when it arrived, so I couldn’t even plug it in! I was a bit lost with the setting up of it. So I had to give my cash, and off he went. Sean came back and plugged it in and lo and behold – everything worked. It had sat for three years in a warehouse. Whenever you power up this old gear, it’s a bit of a hold-your-breath moment, but that’s all part of the charm.

“So the lathe was a similar thing, Sean had another contact who had bought one and had it, again, in storage. It was all in bits – again – so I couldn’t test it but, yet again, Sean just said: ‘Trust me, it’ll be fine!’ I took the deal and there was the foundation of my studio and two of the most important objects in my life.”

MT: So Black Saloon was built on these foundations?

MP: “I’d borrowed some EMI stuff from The Exchange when I first left, and just gradually bought more and more equipment. But like I say to students – It’s not all about the gear, the gear makes your life easier, but I’ve mastered on a Mackie 24-track mixer before and I’ve mastered in a hotel room with just a soundcard, a laptop and a pair of headphones. Top artists, too. My philosophy is that the tools just make our life easier and we all have tools that we like to use, but it’s based on the ears, fundamentally. Anyone can change sound. We do it every day, adjusting the volume in our car to suit the environment. It’s the same principle.”

MT: Is there any piece of tech you use quite a lot?

MP: “Well, all of it, really! But the Prism ADA-8 or any of the Prism converters, really, I’ve got the Orpheus and the Lyra as well. I take the Lyra out and about with me when I’m travelling. I use Prism’s SADiE and MAGIX Sequoia in terms of DAWs, as well as Pro Tools, of course, which is on my laptop. I run a MacBook but I often Boot Camp it into a PC to use some of the PC-only stuff. I’ve got a box to take modules out of my EMI TG desk to travel with me. It’s a very big lunchbox, in a sense! Customs is a nightmare, because everything has to come out…”

MT: One of the things you’re widely known for is your work with Björk, on Biophilia is particular. How was that experience?

MP: “I mastered Biophilia as an album, a conventional record – all the miscellaneous app stuff came later. The app stuff they did in collaboration with Apple. It was just the stems that went in there, but I did help to check some of those. Working on the album was incredible, it was a really hard record – because she’d written all of the tracks in MIDI and then commissioned these instruments to be made, acoustic instruments that were going to be triggered to work by MIDI. As the instruments were being delivered, because the rest of the audio had been made, the tonal sound of the acoustic instruments was different to the MIDI instruments – it was quite hard to get it to work the way she’d envisioned it.

“So what happened was, she’d had everything mastered (by someone else) and she wasn’t happy with it, she went away and had a break and then returned and said she needed to find someone else. A few of her friends were clients of mine and recommended me to her. My ethos is all about realising what the artist wants. So it’s not my place to tell anyone what’s ‘wrong’ with their mixes. And it’s sometimes not all about technical perfection: I’ve done quite a bit of remastering of some old Northern Soul stuff, which wasn’t technically ‘right’, but emotionally, was perfect.”

“So Björk’s friends knew this about me and knew I was coming at it from an artist-centric perspective, and I wouldn’t question technically what they had done… So many engineers question what creatives have done. I’d never worked with Björk before, or anyone one-to-one for that matter, before. I’d always been parts of teams on projects. We had quite a tight deadline. I flew to Iceland on Saturday morning and we needed to deliver the finished tracks to Japan on Friday. There was a lot of pressure and deadlines to be met.

“We spent a day playing back everything and going through everything, all the emotional intention. Really, they sat me in front of the mix, they didn’t have stereo bounces. The mixes weren’t finished. So with Björk at the controls, we finished the mixes to how she wanted. Björk works on a project for three years or more, so lots of different elements become involved, the music is constantly evolving. She’s very clear about how she’ll want her vocals to sit and different intentions of different parts of music. It’s like classical composition. Nothing is the same. So I did a 36-hour stint on Biophilia, with occasional 20-minute breaks and lots of coffee. But Björk is incredible, really humble – very clear about what she wants. A great producer, in that sense. It was a great piece to work on. We did the film and the remix album, too, and then we did Vulnicura which was a similar kind of process. But a very different project.

“I like artists who change and evolve, but I respect what artists do in general. I’ve worked with Feist for four albums now, and she has a very particular way of working, a very particular sound that she wants to put across… and our relationship just works very clearly.”

Keep It Pro

One of Mandy’s biggest concerns right now is the undermining of the professional world of music production by the next generation…

“My biggest thing is that the next generation need to keep the industry professional and charge for their work,” Mandy tells us. “If you’re working with unsigned, unfunded bands and you do work for free, then okay… but if that band go on to sell that record and make money out of it, then you should get paid for your work. Any work that generates income should result in you being paid. It’s a professional industry, and that’s my biggest worry. If they don’t change these models now, I foresee it being more of a ‘hobbyist’ world.

“Back when I came into the industry in the 80s, we had a ridiculous number of studios. This was before we had bedroom producers – which came in the 90s, which I watched and went through. But back in the 80s, it was tough to get into the industry. I was an A-star student and had ADD. So I was hyper-focused – despite all that, it took me around three years, to get a job that was paid. If we look now, we don’t really have studios anymore, but we have all these music-technology students coming into the industry. But a lot of young people are giving it away for nothing.”

“So now, because so many younger producers are giving away their skills for nothing, even established producers, engineers and studio staff are frequently being expected to work for nothing – which is infuriating for someone 33 years into their career. What I’m doing right now, with a team of education people around the globe, is coming up with models for these young people so we can keep it professional and make sure they get paid. A big part of it is that the wider public don’t understand the value of music and the amount of work that goes into making a professional-sounding record. If we took all music away from the country for one day, then can you imagine the effect? People don’t understand how much they’re interacting with it, and with streaming, people have access to everything!”

MT: Do you have any particular genre that you prefer working with, musically?

MP: “No, it’s all just music to me. I like all of it – my opinion is that it’s more about the passion of the music, that’s the important thing. I like the challenge of new genres, I find techno quite a challenge, although I think Björk would sometimes call herself a techno artist. Although I’m not sure how many people would share that view – it’s a tapestry of genres. I’ve worked with some of the top techno artists in the world, yet that’s a genre that I really have to get into a particular headspace for. I always do a playback of the whole album before I master and some albums, it’ll be really easy and instant to zone into the mood and feel of the record, which helps me decide what I’m going to do, why I’m going to do it and it’s a lot easier. With other records it takes longer. I might have to play six or seven times before I have a decision about where I’m going to go with it.”

MT: Can you tell us more about your work on Aphex Twin’s Syro?

MP: “I had spent a few days listening to it, trying to get my head around the direction. It was right after a very full-on project with an indie band that I started and just worked through the night, from 11 to around eight in the morning and basically nailed it. But I needed to be in that particular state – it was absolutely crazy after working a whole day – but yeah, I just came in, dimmed all the lights and had a bit of a geek party on my ownwhile I was doing it. That was how I mastered Syro. I had my own little rave. It was a fun session”

MT: Did any of that pressure come from the fact that this was his ‘return’ record?

MP: “No, I didn’t actually know who he was at the time! Well, I knew he was Aphex Twin, but I didn’t actually know him at all. He’s also really good friends with Björk. I hung out with him and his wife at the Björk aftershow party, when she played Alexandra Palace. We had a great time and then he messaged me saying he wanted me to do a mastering try-out for his record. So we’d known each other, not really closely, but I’d been in his social circle for a while.

“We’re under NDA with everyone, so I didn’t really know how big that record was for him until it launched. We had to deny we were working on it if we were asked. Aphex Twin has the maddest fans! I’d never watched his videos or anything; I’d mastered the stuff and had great conversations with him, so I was really taken aback by how ‘out there’ the videos were!”

MT: What are the key skills you think a good mastering engineer requires?

MP: “I think patience is key, to be able to listen and interpret what the production team want. Have a huge array of references – that’s also a big thing. Part of our training was just to sit there for hours, listening. Not actually ‘doing’, just listening. The next five years of training was just honing in on what you’ve learned. I call it homework, just listening to other records and things you wouldn’t normally listen to. We have this thing that art needs to stand on its own, for the artist. But it needs to fit into the world as well, contextually. If it’s going into playlists, then you don’t want it to sound weaker than what’s around it in the music landscape. So do your homework!”

MT: How important do you think it is to master tracks with an ear on streaming platforms and final distribution, etc?

MP: “I think it’s really important, we have to do a lot of homework on it – we took five tracks (these were big tunes) and captured them back into a DAW from 15 different streaming platforms. The WAV files were terrifying. We have lots of issues delivering WAV files; as a format, it’s not a great one to use as a delivery medium. It’s not stable. I’ve been lecturing about it for about 10 years. We need a closed format, really, that no-one can mess around with. Vinyl, tape, CD – no one can mess around with those things! They’re locked. It was stamped on there… finished.

“People do awful things to those WAV files – burning a CD with soundcheck on, bringing it back into iTunes after they’ve burnt it. Converting it to an mp3 and then back to a WAV file. Each time was a new layer of compression. A lot of digital distribution companies drop data from your final WAV file. You send them a 44.1khz, 24-bit track and they’ll remove eight bits to fit their standards, leaving it sounding horrible! I wish more people knew about this, but these are things that we’re working on addressing.

“I long for the days of Quality Control, and I’m trying to bring it back. I will always QC the vinyl we master. Some factories now have QC sheets that they send out to their clients. They didn’t have that five years ago. It takes time and if you educate and communicate, then people will learn. Look at the lengths some early producers and engineers went to, like Pink Floyd for example. After all this time, it still sounds really amazing!”

MT: So it seems like you’re always on the go project-wise, what’s next on the horizon for you?

MP: “Well, a lot of them are NDA! I’m involved with a great many different bodies, such as The Music Producers Guild and PRS. Lots of collaborative stuff centred around mentoring young people. That’s important to me. It can be a very daunting industry to step into straight out of college; we’ve had a lot of discussion about female professionals coming into the industry this year, which is great and obviously very worthwhile, but for me, the main focus is always keeping it professional.

“We need the industry to become more diverse, but that’s going to take time. I think we’re all actively working on that. We’ve got loads of people from different backgrounds and sexualities in the industry, which is a great thing. But, like I say, I’m worried about where the industry is going to be in 10 years time! [See Keep It Pro boxout].

“To run a professional studio costs money, there’s staff that need paying, accountants… I have a dedicated internet line in this studio which costs £500 a month! There are so many costs. Not to mention insurance for all the gear in here. Mastering is a highly skilled job – though home mastering is encouraged, in terms of getting people to start thinking about the process, but you do need to check those tracks on a full-range system.”