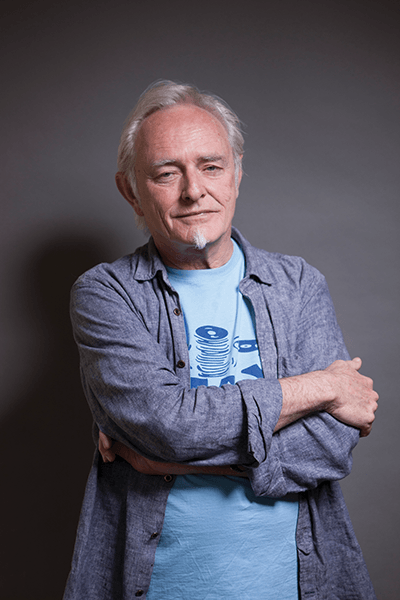

‘Mix Master’ Mike Howlett – The MusicTech Interview

Grammy-winning record producer Mike Howlett has received a PhD in music production, become an in-demand lecturer and helped launch the MPG Awards. Oh, and he’s written, produced and played on some iconic music, too. Who better to open up a new MusicTech series on legendary producers? Mike Howlett is pondering the reasons for the record […]

Grammy-winning record producer Mike Howlett has received a PhD in music production, become an in-demand lecturer and helped launch the MPG Awards. Oh, and he’s written, produced and played on some iconic music, too. Who better to open up a new MusicTech series on legendary producers?

Mike Howlett is pondering the reasons for the record producer’s existence – his own existence, if you will – and if anyone knows the answers to these questions, it’s him. As the first in our series of interviews with legendary producers, we’ve started at the very top. Howlett produced records back in the late 70s and early 80s that defined at least two genres of music.

He picked up a Grammy award along the way; a Doctorate in Record Production in the 2000s; he lectures in the subject around the world and even found time to help set up the Music Producers Guild Awards nine years ago.

We’re currently talking about how the role of the producer has changed over the years, but Howlett doesn’t agree that the principles behind it have altered that much at all…

“There’s been an expanded definition of the term,” he says. “Someone like Calvin Harris; he’s the producer, the writer, the artist – he’s everything, and I love that. Prince was an earlier figure moving that whole thing on, with just the musicality rather than the process.

“But there is also a train of thought that says ‘I just stick a microphone on it and catch the whole thing,’ but that is bullshit. Which microphone are you going to use? Where are you going to place it? You’re in the business of using this technology to create a musical effect: that’s what the producer’s job is – to make the music work as a recording.”

“You’re in the business of using technology to create a musical effect: that’s what the job is”

Which is refreshing to hear, especially from someone who has been involved in production for four decades now. It’s been a long journey, though. Howlett was born in Fiji and raised in Australia and he started out by playing bass. This would lead him not only to the other side of the world, but eventually to the other side of the glass.

“I became a professional musician at the age of 18,” he recalls, “working with a band in Sydney called The Affair. We ended up winning an Australian ‘battle of the bands’ competition, the first prize of which was a trip to London, where I ended up staying!”

Super harmonics: The music we feel

“When I was researching my PHD, I came across ‘super harmonics’ in music, being studied by Professor Ohashi from Tokyo University. He examined people with EEGs measuring brain activity and concluded when you hear music, you get a reaction with super harmonics – so, sound at 30, 40, 50 and 60kHz. These unfiltered analogue signals will trigger areas of the brain that we associate with happiness and well being. The question is, are you detecting it with your ears or with your brain?

“He’s talking about 60kHz: no one hears that, no one hears about 20kHz, but somewhere we are able to process it. Rupert Neve gave a talk about how he met Professor Ohashi and went into his studio where he had a mixer set up with four faders and asked him to listen through all four channels and say which he liked best.

“After about 20 minutes listening, he chose one and through the glass in the studio, all the students burst into applause. They could tell from his body language that he’d chosen the unfiltered analogue channel. What we don’t know is how we perceive it. Rupert said he could feel something. I think it’s physical.”

“I built a synth with a wooden frame that I painted green. I put Letraset on it. It looked great”

Mix Master Builder

Howlett joined the legendary and influential band Gong in 1973. Their album Flying Teapot became the second release on Virgin Records, although it was actually released on the same day as Tubular Bells.

“Tim Blake was the synthesiser player in Gong and it was the first time I’d seen technology like that,” Mike remembers. “It was the Synthi A, a suitcase, matrix thing, a wonderful device – and he was a pure synth player. We were really musical, and he was really good at noises that made it all sound spacey and futuristic.”

“When I left the band, I started messing with the technology myself and I spent two nights a week in college and learnt basic electronics. I actually built a synth with a wooden frame that I painted green. I put Letraset on it and it looked great – it was a real pukka thing. My only regret was that it got destroyed in a studio fire about 15 years ago, but I learnt a lot about the technology from that.”

By this time, Howlett also learnt that he was not cut out for being in bands full time, a decision that would throw him on course for production…

“I was fed up with spending too much time together on buses or on tours. I realised I wanted to make music with various people, but then move on so you don’t get to that point where everyone hates each other.

“I was the last man in Gong and did an album with Nick Mason producing. He was brilliant. He gave me such confidence and taught me everything. He gave me the understanding of the artist in the room and the producer’s role. Also that it’s not about the microphone – that’s important, but down the line – it’s all about the performance in the studio.

“So I wanted to be a producer and I was also fortunate because my girlfriend was the head of Virgin Music, Carol Wilson. She is an amazing woman and the one who found and signed Sting, OMD, Martha And The Muffins and more. I started to produce little bits and pieces and the first single I did was Don’t Dictate by Penetration [now regarded as a punk classic] and it only got to No. 38.

“You ask yourself: ‘What is a hit song? What are the components?’ In fact, I did a PhD, where I analysed five hit records that I had produced. And I hadn’t actually thought about it until that point, but each time, we had identified – that is, me and the record company – a song, and we thought: ‘This song could be a hit and if we get everything right, we will have a hit’.”

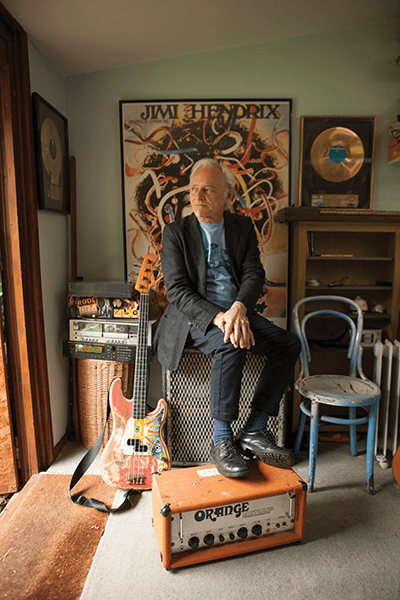

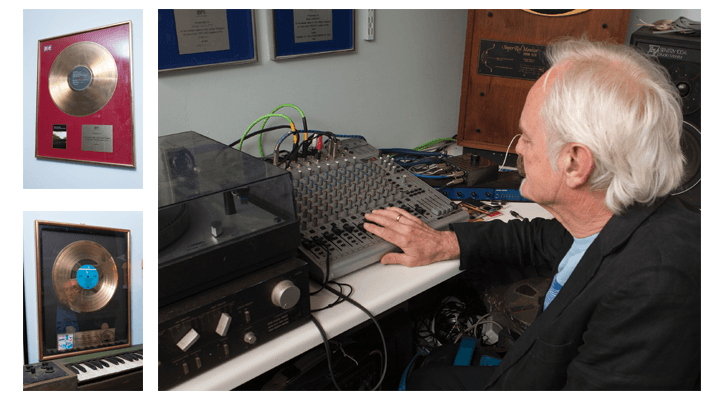

The Howlett Studio

“It’s really basic,” Mike says of his current studio setup. “I have Pro Tools on a MacBook Pro. I don’t have any hardware any more, apart from my Synthi A 100 and that is fantastic, so I mess with that, and I have an old Orange bass amp which sounds gorgeous. I have a 1962 Fender Precision Bass I’ve owned since 1969. When I moved to Australia, I got it valued for insurance; it turned out it’s worth £15k, even in its slightly battered condition. I paid $200 for it in Singapore! It sounds amazing, I do nothing to it to make it sound great.

“I really like the Universal Audio stuff. All their simulations are great and I love their hardware. I think there are some really great leaps forward. You look at something like Ableton Live and it’s kind of the next level, throwing everything in to allow you to improvise and play live.”

MT: And of the current return to analogue synthesis?

“It’s funny, I was thinking the other day about how all these kids are going back to analogue synths. Back in the 80s, I was thinking analogue synths would be the new Fenders and Gibsons – perhaps now we’re seeing that!”

Legendary advice

Throughout his production career, Howlett has maintained his mantra that the song is key. However, next on the list is the arrangement itself and here, Mike has some great advice.

“Think of the arrangement in frequencies, you know: is the bass in the right place? Is the midrange cluttered? Why can’t you hear the voice? Is it because there’re five things in the same bandwidth, all struggling for your attention? Think of it in terms of frequency and that’ll make life a lot easier.”

He’s also very much an advocate of seeing bands live, because a good performance in the studio will very much depend on how a band plays live…

“Has the performance got any magic? Do you get that little tingle, whether it’s from the backing track or the singer, especially the vocal? If a vocal doesn’t cut it, it’s just a piece of crap, you know? You might spend a lot of time getting a great snare sound, but so what? It’s about the song, arrangement, and performance. You can’t start with a good kick and snare sound and then have a mediocre song. It’s so obvious, yet so many people try and go the other way. ‘If only I had that old analogue valve gear from the 60s, then my record would sound good.’ Give me a break!”

Hit-maker

“We identified Enola Gay from the demos as being the next single,” Howlett continues. “I didn’t do very much to change the arrangement on that one. Structurally, it was a lot better – I thought it was fine and exactly right. It had a cheesy Roland drum sound and the bongo ‘diddle-iddle-id’ fill which I thought would be really good going from left to right, so we laid down the tracks to do that. It was just directing the performance – the riff was so strong throughout.”

“The future was going to be synthesisers and computers, but it’d be warm and human”

The song would prove to be a massive hit for OMD and one of the key songs in a synth-pop movement that included Soft Cell, Blancmange and Depeche Mode, where catchy hooks and melodies would lull you in, but the overall message was often a lot darker.

“Kraftwerk showed us the way,” says Howlett. “The psychology was that the future wasn’t going to be cold and futuristic, it was going to be synthesisers and computers, but it would be warm and human. Part of the plot was to write a song that felt like a warm, loving pop song using synthesisers, making it purely electronic but giving it an ironic edge.”

The next single was Souvenir and, by this time, the band had built their own studio in Liverpool with a huge live space that a local choir used to practise in, which the band would use to their advantage…

“The choir would be outside the control room and there would be a few mics lying around and they would do this warm up where they would sing one note all together for 30 seconds and then sing the next note and go up the whole scale. So OMD realised their opportunity and recorded these notes on different tracks and that, if you listen to it, is the breakdown in the middle and the chordal thing throughout.”

Since then, Mike’s gone on to produce acts including The Alarm, China Crisis, Stephen Duffy, Joan Armatrading, Gang Of Four, and Comsat Angels. As production budgets dried up, Mike took an active role in setting up the Music Producers Guild and its annual MPG Awards.

“I was a founding member, but producers like Tony Platt and Robin Millar were the main drivers. We pushed for a long time for producers to get performance royalties the same as the artists and record companies. We achieved this in the UK and most of the world outside the US… The MPG is the only voice fighting for record producers.”

So in closing, what is Mike most proud of?

“The Gong stuff still stands out. In the 80s and most of the 90s, it wasn’t cool. I’ve always thought what we did was astonishing and now it’s being recognised again. We’ve even been talking to Universal about releasing a boxset, so we’ll see.”