Prodigy engineer/co-producer Neil Mclellan remembers the Jilted Generation sessions

When a band has no time for so-called “big studios”, you have to pull something pretty special out of the hat. Through experimentation and happy accidents, engineer and co-producer Neil Mclellan was able to do just that.

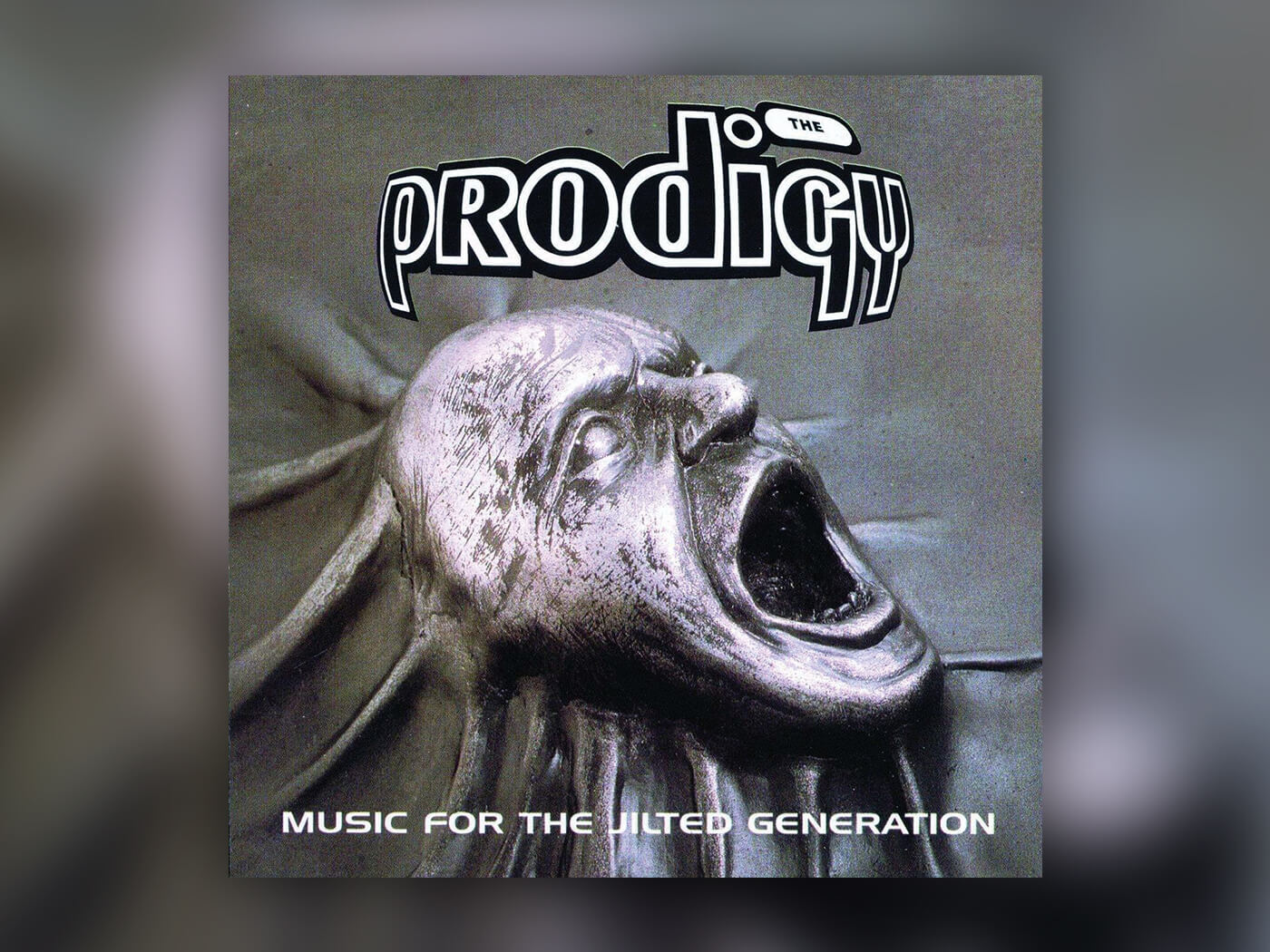

A quarter of a century ago, The Prodigy released a hard-hitting record that saw Liam Howlett’s band embrace working in a professional studio, albeit reluctantly.

We catch up with the band’s long-time engineer and co-producer Neil Mclellan to listen back to the album he recorded and mixed, and offer some fresh insight into the production approach that spawned this seminal LP.

Home work

Like their debut album, Experience, production and programming for Jilted was largely completed in Liam Howlett’s home-recording facility, dubbed Earthbound Studios, in Essex. The nerve centre of the production was a Roland W-30 keyboard sampler and sequencer. Considering the limitations of the hardware, it seems astonishing what was possible.

“All of this was with 1MB of sampling memory. If you wanted to sample something like a kick drum, you’d put the sample rate down to 15kHz, because it would give you more sampling time,” explains Mclellan.

As well as all the samples being triggered by the sequencer, external instruments were also connected, including a Roland TR-909 drum machine. Between Howlett’s production prowess and Mclellan’s mixing abilities, the pair were able to create mixes at Earthbound that were a high enough standard to match up against other acts of the day. Part of that was a dedication to using a lot of compression and using sidechaining to make sure that the mixes could breathe. For the Earthbound sessions, Mclellan chose to rent dbx 160XTs.

“Why did I hire dbx 160XTs for all the programming at Liam’s house? Because it was the cheapest compressor on the list. I had to get at least 16 compressor chains going. FX Rentals had a shit-tonne of them and they gave me a deal. If I could have afforded to have 16 UREI 1176s, I might have done that, but they’re not fast enough. I needed something fast that was going to squash everything and be within budget.

“I can honestly say I don’t think I’ve ever used that many dbx 160XTs ever since, because I suddenly became well known and I generally got better budgets.

“But that’s the sound. It’s the limitation. It’s not like at the time you’re thinking, ‘I’m going to make something different.’ You’re just thinking, ‘I’ve got to get the job done and will this do it?’ Then years later, everyone says that it’s got a sound,” states Mclellan, incredulously.

Apart from the array of compressors, the mixing setup was relatively modest. All of the different instruments and device outputs were brought together using a stalwart Mackie 3282 32-channel mixing desk. “It was an amazing board. But we couldn’t get any more out of it at Liam’s place. We decided, at least on the singles, to go and spend the money going into a big room and make them fat as fuck.”

Studio Upgrades

However, according to Mclellan, convincing Howlett, the band’s driving force and production talent, to set foot in a professional studio was quite a challenge.

Howlett was understandably apprehensive. As far as he was concerned, “nothing he did in the big studio came out sound like it did at home”, recalls Mclellan. The band felt it was “too soft”, he says.

It wasn’t just Mclellan pushing for studio time, though. When it came to the singles, both Mclellan and Daniel Miller, the chief of Mute Records – the band’s label in the US – demanded they enter the studio.

“From my perspective, it was about maintaining the raw energy of the demo with a band that was totally sceptical about walking into a big studio.”

“So we went straight into a big room where we could hear all the frequencies and really get that going,” recounts Mclellan. For other acts at the time, the norm was to mix tracks at home, often in less-than-ideal listening environments, then put the mixes onto DATs and send them for mastering. The fact that no other band of their ilk was working in professional studios, meant that doing so could give them an advantage.

But now the band had decided to enter the studio, London’s famous Strongroom Studios, Mclellan had to give them the sound they wanted. “From my perspective, it was about maintaining the raw energy of the demo with a band that was totally sceptical about walking into a big studio.”

In the end, five songs from Jilted were mixed at the Strongroom, including Voodoo People and No Good (Start The Dance).

In The Red

“From where I was looking at it, if I made it ‘correct’ for the day, it would be too soft for Liam, Keith and Maxim. They wouldn’t have liked it. So you go into this place where it’s a bit like when The Beatles decide to overdrive everything at Abbey Road. I was in the same place, dealing with a band where I’ve got to pull that sound out, so I drove everything hard,” says Mclellan.

“I tried to push everything into the red and keep it musical, as much as I could. Because I knew the opposite direction was something they wouldn’t like.”

Now working in a big studio, a massive differentiating factor for the band was that they could make use of the ambience of the studio space.

“We just mic’d up everything that we could,” says Mclellan. “I mic’d up the live room. I fed everything into it. I tried to recreate a live feeling. On top of that, if you listen to Voodoo People, it’s all compression, just trying to make everything fit it. That and overdrive.”

To get the overdriven sound, Mclellan explains, “I was distorting the Neve. It’s great, because we took those boards and turned them on their heads, really. If it was a line level, we put it in the mic input to see what would happen. While it might not be distorting the signal, it’s definitely overdriving it,” he explains.

Creative Equalisation

Another technique involved using the Neve’s built-in EQ to create filter sweeps on delay returns. “There’s a whole bunch of filter movements. I’d take delay returns, bring them up to a channel on the Neve and then if you use a really fine Q, turn the gain to 11 so you’re getting 12dB and sweep through the frequencies, you’ve got your own built-in filter. There’s a lot of that going on,” he tells us.

None of this was automated, either. “We recorded to tape. Everything was recording and if you liked something that was good, you might sample it and put it in. But really, it’s about the performance at that point. If you liked it, you just recreate it. And then punch in every time you wanted it to happen,” says Mclellan. You can hear the effect on the outro on Goa (The Heat The Energy, Part 2).

“That was a really lovely place to be in terms of being able to make something new. The Prodigy back then, they wanted something different and that gave me a licence in front of the board to really push it.

“Within that, you still have to make mixes that sound awesome on the radio. That’s the one thing about these records. They cut on an Auratone and yet they’ve got enough bottom end on them,” says the engineer.

Low-end theory

Part of the secret of Howlett’s approach for a cohesive low end is the tuning of his kicks and basses. “Tuning of the bass and tuning of the drums. Nobody ever does this and Howlett is a master at it. With the Prodigy, we would go through and fine-tune the kick so it fitted throughout the track.

“The changes in tuning could be quite drastic. For example, if you have a 909 and you pitch the kick up a semitone from one section to the next, 99 per cent of people won’t even notice because it feels right,” asserts the engineer.

If you’re re-pitching kick drums to fit with your bass, the downside is the perceived loss of low end when the kicks are transposed up. To combat the loss in the bass, Mclellan used mute automation on the console to bring in a dbx Boom Box subharmonic generator.

“On the bits where the pitch went up,” says Mclellan, “I would just feed a little bit more in until I could feel it was still smooth on the bottom end. Balancing out those sub movements meant you never notice it. But pitch-wise, we were always in a lovely place with the drums.

“It’s one of the things that most people overlook. It’s sitting there and really tuning your drums to your track.”

Track my pitch up

Mclellan holds a similar drum tuning philosophy for real drums, too. “If you’re recording a live band, fuck everything else. Spend the money on a drum tuner. Get someone in who can tune the drums to the key of the track. If your drummer can’t do it, get someone who can and then listen to what happens to the kit. You don’t ever have to gate anything. You just leave everything open. It just flows into the tuning of the track. There’s no hard work to do. It’s preparation. Go back one stage and fix that. The thing that you’re supposed to be doing in the big studio at mixdown is having fun, not having to go and fix a billion things.”

Voodoo People

Listening to Voodoo People for the first time, Mclellan recollects thinking: “There’s a lot going on”. Fortunately, though, Howlett was able to make all the different musical elements gel. “Liam Howlett, to this day, I still think is the best programmer for being able to stick things together. I’ve not come across anyone with that musical sensibility. He’s not a boffin, but he manages to dive in and make it all work,” says the engineer.

The track opens with a distorted-guitar sample based on the opening bars of Nirvana’s Very Ape from In Utero, quickly followed by a driving 909 kick. “There’s a solidness to the 909 when you listen to the decay on it. It’s awesome. It’s going straight into a dbx 160XT [compressor/limiter].

“We printed this all to two-inch tape, back in the day. And we mixed this one on a Neve VR60 desk in the Strongroom,” Mclellan recalls.

Stereo width

Now, listening back to the track with us, 25 years after its release, the first thing that strikes him is its stereo presentation. “Fucking hell. It’s almost mono,” Mclellan exclaims.

“The only thing that’s stereo in that track is the reverb. There’s reverb on the drums. I know that I used the live room at Strongroom as a reverb and I know I used the grand piano as a reverb [more on that later – Ed]. All the chorusing would have been done on a Yamaha SPX90 with Pitch Change C setting, +/- 14 cents on the fine pitch. That was on the main synth and we also used an AMS RMX16 reverb with a 60ms pre-delay,” says Mclellan.

“There’s also a 3/16ths and 1/8th delay on another SPX90, because we loved that effect. That was a thing that we used an awful lot just to give things movement. You can hear it on the breaks as well. It gives this little shuffle movement and it’s got hardly any re-gen. It’s like one or two per cent. Same with the reverb. That’s fed into the SPX90,” he remembers from the Strongroom sessions.

No Good (Start The Dance)

“On this one, we ran out of sequencing space in the W-30 so we transferred over to Cubase on an Atari which gave us more MIDI tracks,” Mclellan recalls.

The track was mixed on the Neve VR60 in Strongroom 1 and, as with the drums on Voodoo People, Mclellan used the live room as ambience. This time it was for the synth break, which you can hear at 0.55 in the track.

“The live room in Strongroom 1 used to have this pair of speakers that were given to the studio. But instead of putting them in a normal place, they put them really high up in the room. And they had them on a buss so you could listen to them, so I’d send it to them from the mixing board.

“They had these EQ settings on the front of the speaker, we had to get up a ladder to tweak them. I took off all the bass, and then just fed that into the room and had a pair of AKG C414s right at the back of the room,” Mclellan says.

Another dimension

Another technique that Mclellan used heavily was a three-fader M/S trick for creating width. By setting up those room mics in a Mid-Side array, he would duplicate the ‘sides’ signal onto another channel and flip its phase.

“On the pad in the breakdown [at 4.05], it’s definitely that,” he says. And it’s not just the pads either. “There’s a whole guitar line that totally disappears in mono,” Mclellan explains. “As you bring up the out-of-phase signal, it starts to cancel out the other channel. You can make it completely disappear, which is totally useless, or you can find a place where it’s really wide. That’s dependent on the amount you turn up the out-of-phase channel.”

Mclellan tells us that a huge part of the sound was making those sounds more ‘analogue’. “I don’t mean analogue, like analogue tape,” he clarifies. It’s, in fact, about “regeneration of signals in a real analogue space – not in the box”.

Goa (The Heat The Energy, Part 2)

Perhaps the most extreme manifestation of the analogue ethos is in Goa (The Heat The Energy, Part 2). The sound of the Roland TB-303 bassline has a distinctive tone as a result of an unusual production trick. Mclellan attached two Auratones to the underside of the soundboard of the grand piano in Strongroom, and close-mic’d the strings. The resultant acid bass is, in fact, entirely the pickup of those mics. This can be heard most prominently at the end of the track where you can hear the resonance of the strings as the noise floor rises. “It just did this thing that gave us huge body on a 303,” he says.

Poison

“Poison, I love. Right at the beginning, you can hear Howlett editing on his AKAI S900 sampler. It had a certain sound on the jog wheel,” Mclellan remarks.

“I learnt so much from Liam Howlett about drums. I was all about slew rate and movement and making sure that the speaker cones are moving outwards when they should be moving out. Howlett is all about feel and groove. The swing on Poison is huge. It’s almost like a New Jack Swing in a weird way, but the two and the four are so solid,” comments Mclellan. “Then you’ve got a 32nd-note ride cymbal on the W-30. Back then, there was always that ride sound, which was hugely important. I always used to make sure it rang out.”

The first version, which appeared on the album, was completed at Earthbound. But, on the instruction of Daniel Miller, the band went to the Strongroom to mix the single version, this time on an SSL.

“I remember driving everything,” says Mclellan. “I was uncomfortable about it, but they wanted more poke on everything. Because everything’s a build on the track, even though it’s already full-on. But then it’s got to find another level,” he explains.

“I learnt so much from Liam Howlett about drums”

That other level is at 2.08 in the track, as Mclellan describes: “There’s a driving noise which is the sound of literally everything at 11 on the board. Everything was absolutely the maximum that it can be. That was a happy accident because as an engineer, I was there thinking I’d got no more room. Every tiny little tweak, I’d start hearing distortion. There was nowhere to go. I took great care on my gain staging, but I was still way over the place I was supposed to be. The mix buss was creeping down and down. At this rate, I thought, I’m going to have this mix buss at -10dB. So, technically, as an engineer you’re going, ‘Well, this sucks.’”

But the band still wanted more. “So I remember pushing the EQ on the group. I was in one of those moods where I thought, ‘You want more? Fuck it, have that.’ It’s that moment where you have a little flip out and you can’t say anything, so you take it out on the mixing board,” recounts Mclellan. Fully expecting the band to be disgusted by this high-pitched noise being cranked up at 1kHz, Mclellan looked back at the band from the desk. Says Mclellan: “Howlett’s just there going, ‘Fuck yeah. That’s the one!’”

And so, one of the most memorable records of the 1990s was birthed, through a series of experimental procedures designed to appease a band that never wanted to be in a “big studio” in the first place.

Read about their 1996 follow-up, The Fat of the Land, which propelled the band to international fame.