Recording Spotlight: The Beatles – ‘White Album’

This year marks the 50th anniversary of ‘The White Album’, a double LP that is as innovative as it is inspirational. We honor this special birthday with a look back at the history, recording techniques, tense studio sessions and the gear used for this incredible double album…

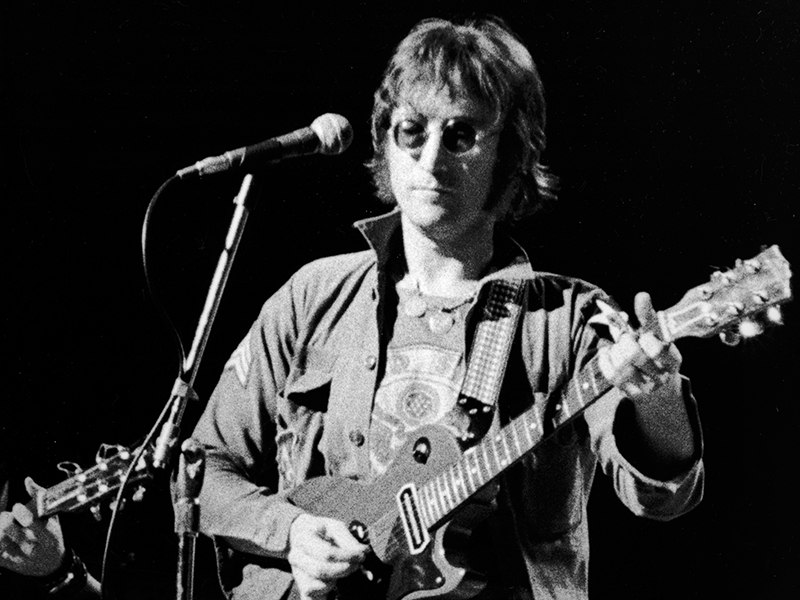

(From left) George Harrison, Ringo Starr, John Lennon and Paul McCartney. Image: John Downing / Getty Images

This year marks the 50th anniversary of The White Album, a double LP that is as innovative as it is inspirational. We honour this special birthday with a look back at the history, recording techniques, tense studio sessions and the gear used for this incredible double album…

On 22 November, 1968, The Beatles released an eponymously-titled double album, now known universally as The White Album. Recorded as the follow-up to their groundbreaking Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album, The White Album contained a multitude of musical styles and sounds across its 30 tracks. Although the group abandoned much of the psychedelic studio wizardry of Sgt. Pepper, they continued their quest for new and interesting sounds, albeit in a more organic, back-to-basics way.

Indian inspiration

When The Beatles returned from their trip to India in May 1968, they were armed with around two-dozen new songs. The long, hot days studying transcendental meditation under the tutelage of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi produced a wealth of new songs from John Lennon and Paul McCartney as well as several from George Harrison, now flourishing as a songwriter in his own right. Even Ringo Starr got in on the act, finally completing a tune he’d been playing around with for five years.

The Indian sabbatical hadn’t gone entirely to plan, with Ringo, unable to stomach the spicy food, leaving after only 10 days. Paul McCartney stuck it out for two months before returning home to take care of business concerning the group’s new Apple organisation. When John and George finally arrived back in London in the middle of May, they too had become disillusioned with the experience.

The group convened towards the end of May at Kinfauns, George Harrison’s bungalow in Esher, to record demos of their new compositions on George’s 4-track tape machine, before presenting them to producer George Martin. ”They came in with a whole welter of songs – I think there were over 30 actually. I was a bit overwhelmed by them and yet underwhelmed at the same time because some of them weren’t great,” he later recalled in The Beatles Anthology documentary.

With none of the group prepared to sacrifice his own material, the decision was taken early on to make a double album, against George Martin’s wishes. ”I thought we should probably have made a very, very good single album, rather than a double. But they insisted. I think it could have been made fantastically good if it had been compressed a bit and condensed.” Clearly, the producer no longer had the whip hand in these matters.

Recording pressures

Many close observers noticed a change in the group dynamic upon their return to work at EMI’s Abbey Road Studios on 30 May 1968. John, rendered passive through his intake of LSD during 1966 and 1967, had new-found fire in his belly and sought to take back control of the group from Paul, the domineering force throughout the psychedelic era of Revolver and, especially, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Adding to tensions within the group was the presence of John’s new love and constant companion Yoko Ono. Wives and girlfriends had previously been discouraged from attending recording sessions but now Yoko was beside John at all times. Making matters worse, she soon started to express her own opinions about the group’s work, much to the annoyance of Paul, George and Ringo.

The first track recorded was John Lennon’s (as yet unnumbered) Revolution, a politically-charged song he intended to be the group’s next single. Recording onto EMI’s Studer J37 four-track tape machine, with engineer Geoff Emerick manning the controls of the REDD.51 mixing console, The Beatles attempted to perfect a backing track comprising piano, acoustic guitar and drums until they nailed it at take 18.

Running for over 10 minutes, the final six minutes descended into a cacophony over which John repeatedly screamed. This final section later formed the basis of Lennon’s experiment with musique concrète, Revolution 9. The following day, bass guitar and vocals were added to the track; however after a weekend break, John decided to redo his lead vocal. Geoff Emerick was unavailable so Pete Bown engineered this vocal session. Technical engineer on this session was Brian Gibson, who recalls John wanting to record his new lead vocal lying on the studio floor singing into a Neumann KM56 suspended above him.

Work continued at the beginning of June with the recording of ’Ringo’s Tune’, which would eventually be titled Don’t Pass Me By (after a brief spell under the working title This Is Some Friendly) before George and Ringo left for a trip to the USA on the 7th, not returning until the 18th. This was an unprecedented move as never before had a Beatle left the country while recording sessions were in progress.

Recording continued in their absence on 11 June with John spending more time on Revolution 9 in Studio Three, while Paul recorded Blackbird alone in Studio Two. This was the first time group members worked on their own material simultaneously in different studios; however, as sessions progressed, this became a common occurrence. Three sessions booked for 12-15 June were cancelled in George and Ringo’s absence and then Paul also travelled to the USA, putting sessions on hold until 26 June, when the group reconvened to tape John’s hard-rocking Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except For Me And My Monkey.

The 3M M23 eight-track tape recorder

By 1968, several London studios were offering eight-track recording. EMI, however, were still using their trusty Studer J37 four-track machines and although some sessions for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band had successfully synced two J37s, the process was tricky and unreliable. With Studer’s A80 eight-track still in development, senior EMI engineer Malcolm Addey visited several eight-track studios in Los Angeles searching for a suitable alternative.

The American company 3M (Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing) had released their first eight-track recorder the M23 in 1966, boasting better signal-to-noise ratio and frequency response than any other commercially available machine. Unfortunately, the machine did not conform to EMI’s operating procedures and needed modification before it could be used on sessions.

The main issue was the M23’s inability to output from the sync head and repro head simultaneously. This hindered the overdubbing process, as the sync head was required for musicians to hear the previously recorded track to be overdubbed, while EMI policy demanded that all recordings had to be monitored off tape, using the repro head. Also EMI’s ADT, phasing and flanging tape effects required the simultaneous use of sync and repro heads.

Four is not enough

As sessions progressed into July, with the recording of Paul’s Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da and Helter Skelter, and John’s Cry Baby Cry and Sexy Sadie, the group became increasingly dissatisfied with EMI’s antiquated four-track set-up. Other London studios, such as Trident had already made the leap to eight-track and The Beatles even owned three eight-track machines themselves, yet EMI’s two 3M M23 eight-tracks, purchased in May, just before sessions for The White Album began, remained unavailable, awaiting modifications to meet EMI’s strict specifications.

By this time the tensions within the group were apparent to all concerned and during the recording of Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da on Tuesday 16 July, Geoff Emerick quit as The Beatles’ recording engineer, unwilling to tolerate the bad atmosphere. ”I lost interest in The White Album because they were really arguing amongst themselves,” he told Mark Lewisohn in The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions. ”I said to George [Martin], ’Look I’ve had enough.

I want to leave. I don’t want to know anymore.’ George said, ’Well, leave at the end of the week’ – I think it was a Monday or Tuesday – but I said, ’No, I want to leave now, this very minute.’ And that was it.”

His replacement was 21-year-old Ken Scott, newly promoted to balance engineer. Although The Beatles were the biggest band in the world, working with them was not considered a plum job and more senior engineers, many of whom had young families, were reluctant to adhere to the group’s nocturnal recording practices. To the young and eager Ken Scott, however, the unsociable hours and quick tempers were all part of the creative process, as he told us ”Tension is part of creativity and it will always happen. So spending as long as we did back on The White Album – close to six months – it happened several times.

“So yeah, there was animosity from time to time. But overall things were pretty amazing. Much has been written about their friction during these later years but I just remember them jamming and playing together all the time. There was work going on in different studios but that was because we had to keep working hard to get things done and to try and finish the record.”

Tracklist and initial recording dates:

- Back In The USSR 22 August 1968

- Dear Prudence 28 August 1968

- Glass Onion 11 September 1968

- Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da 3 July 1968

- Wild Honey Pie 20 August 1968

- The Continuing Story Of Bungalow Bill 8 October 1968

- While My Guitar Gently Weeps 3 September 1968

- Happiness is A Warm Gun 23 September 1968

- Martha My Dear 4 October 1968

- Blackbird 11 June 1968

- Piggies 19 September 1968

- Rocky Raccoon 15 August 1968

- Don’t Pass Me By 5 June 1968

- Why Don’t We Do It In The Road? 9 October 1968

- I Will 16 September 1968

- Julia 13 October 1968

- Birthday 18 September 1968

- Yer Blues 13 August 1968

- Mother Nature’s Son 9 August 1968

- Everybody’s Got Something To Hide Except Me And My Monkey 26 June 1968

- Sexy Sadie 19 July 1968

- Helter Skelter 18 July 1968

- Long Long Long 7 October 1968

- Revolution 1 30 May 1968

- Honey Pie 1 October 1968

- Savoy Truffle 3 October 1968

- Cry Baby Cry 15 July 1968

- Revolution 9 30 May 1968

- Good Night 28 June 1968

To trident

Frustrated by EMI’s lack of eight-track facilities, and concerned that lesser groups were benefiting from other studios’ eight-track capabilities, the group decamped to the eight-track-equipped Trident Studios at the end of July to tape their new single, Hey Jude.

Although never intended for the new album, the experience prompted further sessions for White Album tracks at the studio. Trident had been conceived as a rock studio, offering a more relaxed atmosphere for young musicians and a cutting-edge attitude to modern, multi-track recording. Its long narrow recording room was acoustically quite dead, ideal for close mic’ing pop records but not really suitable for large orchestras.

When the orchestral overdub for Hey Jude was recorded, the trombones were placed at the front to accommodate the instruments’ telescoping slide mechanism. Having mixed the track through Trident’s bright-sounding Tannoy monitors, it became apparent they had flattered the mix which, when played back through EMI’s Altecs, sounded dull. Rather than remixing the song from scratch, Ken Scott used Abbey Road’s UTC �’Curvebender’ equaliser to restore the top end.

As work continued at Abbey Road throughout August, a most unusual session took place on the 13th for the recording of John’s Yer Blues. A flippant remark made by Ken Scott prompted the band to leave the large Studio Two in favour of a more intimate setting, he told us. ”You had to be very careful about what you said to them because sometimes they could take things meant in jest seriously, I made a joke to John Lennon one day about recording in this tiny little closet-room by the side of number 2 control room, when I mentioned it he just looked over, stared at it and didn’t say anything.

”Then the next day he came in and said, ’Right we’re going to record a new number, it’s called Yer Blues and we’re going to do it in there,’ and he pointed to the small room. That track was recorded in there, all completely live with no separation between anything. You can imagine how much spill there was with them all just in this tiny room.” The following day John recorded his lead vocal using an old RCA 44-BX, singing halfway between the little room and the control room, to capture some of the sound coming off the Altec monitors, while Ringo doubled his snare part.

The REDD.51 desk

The White Album was the last Beatles record recorded through Abbey Road’s valve-powered REDD.51 mixing console. A few weeks’ after the final White Album session, EMI installed the larger, brighter sounding TG12345, a solid-state console designed to work with the new 3M 8-track tape recorders. As the REDD.51 was designed for use with 4-track machines, mixing the album’s 8-track recordings necessitated an inelegant lash-up of two consoles. The combination of the 3M 8-track recorder and tube-driven consoles was unique to The White Album. The desk’s EQ section was limited compared to that provided by the TG12345, offering 10dB of shelving boost or cut at 100Hz along with treble equalisation operating as a peak-boost EQ centred on 5kHz and a shelving cut at 10kHz.

Ringo goes

The recording of Yer Blues had been an enjoyable experience for the band, offering some respite from the tense atmosphere that had prevailed over the previous weeks. However, events took a turn for the worse on 22 August when Ringo (temporarily) quit the band. In his absence, Paul took on drumming duties for Back In The USSR, while George played electric guitar and John played the Fender Bass VI.

The bass part was later wiped to accommodate piano, guitar and some additional drumming from George. Following this, Paul overdubbed bass with George doubling up on the Bass VI. During this overdub, John contributed more overdubbed snare drum. The shock departure of Ringo inspired John, Paul and George to pull together, with all three making contributions on drums and bass.

On 28 August, with Ringo still absent, the three remaining Beatles returned to Trident Studios to record one of John’s standout tracks on the album, Dear Prudence. Written in India about Mia Farrow’s sister, who would spend all her time meditating, refusing all requests to ’come out to play’, the song features John demonstrating the new finger-picking guitar style he learned from folk singer/guitarist Donovan, another student of the Maharishi.

Recording on eight-track, with Paul once again occupying the drum stool while John and George performed their intricate guitar parts, the group made full use of the expanded track count, filling the tape with bass, piano, double-tracked lead vocals and percussion. The engineer was studio co-owner Barry Sheffield, as Ken Scott – an EMI employee – was not at liberty to follow the group to an independent studio.

Eight-track Abbey

At the beginning of September, Ringo was persuaded to rejoin his band mates, returning to Abbey Road to find his drum kit festooned with flowers. to welcome him home. The Beatles’ experience of eight-track recording at Trident made the group unwilling to return to four-track, forcing EMI’s hand to make their unmodified 3M M23 machine available for all future sessions. Only The Beatles were allowed to use it however; the inability to monitor off tape while overdubbing contravened EMI policy, so other artists were still restricted to four-track until the necessary modifications were made.

The first song recorded on EMI’s M23 was George’s While My Guitar Gently Weeps, a firm fan favourite although he later complained that John and Paul showed little interest in it. George had previously taped a solo demo of the song (later released on Anthology 3) at Abbey Road, which featured an extra verse omitted from the final version. The band had originally attempted to nail the backing track in August on the four-track J37, shortly before Ringo’s departure.

Now, George had the tape transferred to eight-track and experimented with a backwards guitar part before scrapping the recording and starting afresh with a new backing track. Sensing a lack of enthusiasm from the rest of the group, George invited his friend Eric Clapton to play the song’s memorable guitar solo. Remarking that his bluesy solo didn’t sound Beatle-y enough, the solo was processed through an oscillator to produce a wobbly, pitch-shifted tone.

The person wobbling the oscillator was Chris Thomas, George Martin’s personal assistant who found himself in charge when the producer decided to extract himself from the sessions. Chris recalled in The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: ”I had just come back from holiday myself and when I came in there was a little letter on the desk that said, ’Dear Chris, hope you had a nice holiday. I’m off on mine now. Make yourself available to The Beatles’.”

In effect the group were now producing themselves, however the young assistant earned himself a producer or co-producer credit on several tracks as well as playing keyboards. One of his sole production credits was for the rock and roll inspired Birthday, written by Paul on the spot in the studio directly after the group had gathered at his house to watch the 1956 movie The Girl Can’t Help It, starring Jayne Mansfield and featuring Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent and Fats Domino.

The other Chris Thomas ’production’ was one of John’s standout tracks on the album, the gorgeous and musically nuanced Happiness Is A Warm Gun, which proved tricky to nail due to its unusual arrangement featuring odd time signatures. Eventually the process of editing together the first half of take 53 with the second half of take 65 ultimately produced the master take.

Mono vs Stereo

The White Album was the last Beatles record mixed in both mono and stereo, though in the USA it was issued in stereo only. As with previous albums, the mono mixes were usually performed as soon as the recording was completed, with stereo mixing left until the very end of the album’s sessions.

There are many subtle differences throughout – the sound effects in Back In The USSR, Blackbird and Piggies for

example – and some much more noticeable variations. The most striking is Helter Skelter, which is a minute shorter in mono and doesn’t fade back in with Ringo’s concluding shout, ”I’ve got blisters on my fingers!” Ringo’s debut composition Don’t Pass Me By runs faster in mono and features different violin playing at the end. George’s Long Long Long features double-tracked vocals, which are fine in stereo but badly out of sync in mono.

Which version is better? The jury seems to be out on this one with both having merit. Some tracks hang together better in mono, while others – Helter Skelter in particular – work better in stereo. This writer prefers the mono overall with its darker, punchier sound, yet as another listener remarked, ”My White Album must have Ringo getting blisters on his fingers!”

A Trident and Abbey finish

With a release date of 22 November, 1968 set, The Beatles upped their work rate throughout October, with the recording of seven new songs. Taped at Trident Studios at the beginning of the month were Paul’s 1920s-influenced Honey Pie, incorporating a filtered vocal effect and crackles to mimic and old 78rpm shellac record, and George’s Savoy Truffle, featuring a heavily compressed, deliberately distorted brass section. The album was completed during a mammoth 24-hour session at Abbey Road over 16/17 October, when John, Paul, George Martin and Ken Scott compiled the running order and performed cross-fades between several tracks.

Although the sessions sowed the seed for the group’s official break-up in 1970, it remained close to their hearts. Speaking in a 1971 interview he gave to Peter McCabe and Robert Schonfield at the St. Regis Hotel, John remarked, ”I always preferred it to all the other albums, including Pepper, because I thought the music was better. The Pepper myth is bigger but the music on The White Album is far superior, I think. I wrote a lot of good stuff on that. I like all the stuff I did on that and the other stuff as well.”

And addressing that never-ending debate about whether the album should have been condensed into one single LP, Paul summed it up perfectly in The Beatles Anthology: ”I think the fact that it’s got so much on it is one of the things that’s cool about it. I’m not a great one for ’maybe it was too many of that…’, what do you mean? It was great, it sold, it’s the bloody Beatles’ White Album. Shut up!”