USSR VS ADSR – Soviet Synths

The former Soviet Union had a thriving synth industry for many years, and some of the machines built during that era have become classics. Scott Houghton looks back at the block rockin’ comrades from decades past… You’d be right to be mildly taken aback when hearing the word ‘synthesizers’ in the same sentence as the […]

The former Soviet Union had a thriving synth industry for many years, and some of the machines built during that era have become classics. Scott Houghton looks back at the block rockin’ comrades from decades past…

You’d be right to be mildly taken aback when hearing the word ‘synthesizers’ in the same sentence as the ‘Soviet Union’, and yet the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1991 revealed an abundance of electronic music in the former USSR: drum machines and synths like nothing you’d ever heard – a whirlpool of harsh, gritty, sonic tones.

Arguably the first synth, the ANS, named after the Russian composer Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin, was built and developed around 1938 and finished in 1958 by engineer Evgeny Murzin. It was fully polyphonic and generated its tones via graphical sound, i.e., by colour and light. It’s famed for its truly unique ghostly sound, so much so that the Russian film director Andrei Tarkovsky used it for the score in his space epic Solaris in 1972.

Only one of these machines is in existence, but we are lucky enough to have the ANS’s sound available in the form of a free VST.

Don’t be fooled into thinking the ANS is anything like what we would call a ‘modern’ synth, though, as it sounds nothing like what you’d hear in any pop or dance record. It has an eerie ethereal wave, perfect for ambience, and similar to the kind of reverberation you’d hear in a Grimes record or from a Roland Space-Echo.

The Formanta Polivoks: The Soviet response to the lack of western synths

It was during the 1970s and early 1980s that the Soviet Union really began to fully embrace and appreciate electronic synthesis in the traditional sense in a bid to catch up with the West’s technological and stylistic advances, such as the UK’s Synthi and the legendary Moogs of the United States in the 1960s.

Russia’s Moog

The Polivoks is regarded by many as the greatest Russian synthesizer, and nicknamed the ‘Russian Moog’. It’s a 49-key duophonic synth designed by engineer Vladimir Kuzmin and his wife Olympiada at the factories in Ekaterinburg and Katchanar. It is famed for its gritty harsh sound; a sonic nuclear explosion of an instrument.

Although these synths are capable of producing great sounds, many are of varying quality due to the state of the components and the conditions they had to work in at the time, which was at the tail end of the USSR. If you are thinking of purchasing an old Soviet machine, please ask for a video demo first.

Kuzmin has stated in an interview with the Polish synth aficionado Maciej Polak in 2003 that there was “no musical industry in Russia,” adding there were “simply plants manufacturing equipment as part of a programme to increase the overall volume of goods produced for the people. The best engineers worked at those plants, and it was considered economically advantageous for these military and semi-military factories to manufacture non-military products – TVs, radios, tape recorders and so on.

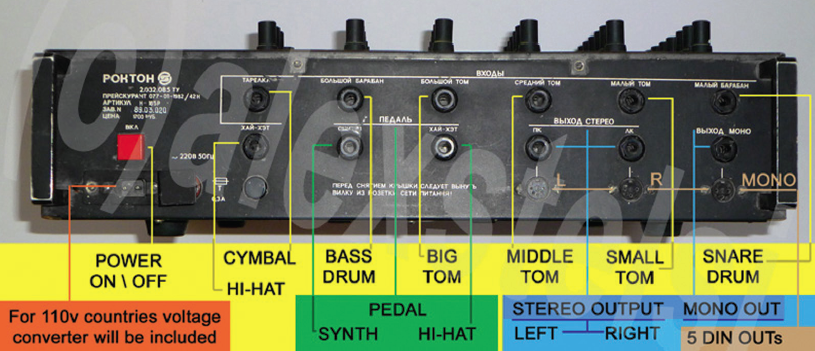

The Rockton UDS drum module could be hooked up to these quintessential 80s controllers

“You need to understand that the socialist economic system was based on a simple principle,” he continued, “statisticians monitored how many families owned, for example, TV sets, and the Party would then decide to increase this number by, say, 20% in the next Five-Year Plan. Then, the Ministry of Planning would formulate plans for the manufacturing plants. But there were too many factories, so the planners had to look for additional products. This explains why Russia produced so many electronic musical instruments; they were proposed by enthusiasts to keep the plants busy.”

As these Soviet machines were produced in mainly military or semi-military factories, a great deal are incredibly heavy. For example, the UDS weighs a considerable amount due to it being fashioned from anti-tank plating. This holds the machine in good stead if you’re gigging, yet it’s increasingly tiring carrying it around.

The ins and outs on the rear panel of the Rockton

With such good plating you’d be forgiven for thinking this would protect it internally too, yet the circuits in many of these machines can be easily damaged or worn away over time, which means buyers need the devices servicing by someone who is familiar with Soviet electronics beforehand.

Kuzmin stresses that Russian musicians at the time wanted electronic instruments but couldn’t afford Western synths such as Rolands and Korgs, therefore the USSR produced its own. Many of them are simple emulations of Western models, with two voices of polyphony, two oscillators each with triangle, square-wave and saw-tooth, two types of pulse waveforms and one noise generator.

Different Russian synths each have their own particular snarl because of the unique components used within the instruments. For instance, in the Polivoks Kuzmin decided to bypass the Western tradition of a 24dB/octave filter and develop his own filter mechanics. He chose a very simple 12dB/octave device which humbly accommodated two co-amps and six resistors, which offer low-pass and band-pass responses. The overall design also disregards the notion that analogue synths need capacitors to work, and the end result is a very distinctive sound, one with harsh tones that many have grown to like.

The Aelita is a mono synth with a good range of parameters to control the people’s sounds

The Polivoks could be considered an early maverick for its day, as it can be used as a signal processor: on the right side of the panel is the gate switch which enables you to utilise these capabilities. But perhaps its most interesting feature is that VCO1 can be cross-modulated with VCO2. In addition you can also play around with the attack and decay generators, giving repetitive and very textured polyrhythms. On the left side of the Polivoks you have the infamous filter cohort, the top half being a standard ADSR, yet with a simple flick of a switch it can be set to loop.

The mighty Rockton UDS drum machine

The Modular Age

Kuzmin decided to take a modular approach to the Polivoks, resulting in separate sound-generating sections for its own circuit board. These boards could then be inserted into the back panel of the Polivoks, enabling the circuit boards to be updated and/or repaired if necessary.

Once you use a Polivoks it becomes clear that you are dealing with something very unique indeed, from the sound it generates to its controls, whilst still obeying the universal language of synthesis. However, it is easy to understand for anyone who has previous experience with analogue synthesizers, like a Korg MS20 (or you could have the seller translate the writing on the various dials and knobs for you).

Today if you want the sound of the Polivoks there are a couple of ways. The modular synth company Harvestman has now teamed up with Kuzmin to produce the Polivoks VCF (around €200), a modular clone of the Polivoks’ filter which can be integrated into modular systems to create some very interesting sounds. For modern-day producers there is also a VST, named Polivoks Station (now at v2.2 and free), made by Syncersoft, which is definitely worth checking out, although it doesn’t really compare to the feel of the original.

Built in the same factory as the Polivoks, the Rockton UDS drum machine again provided a unique take on a standard piece of kit

Wait, There’s More…

Soviet synths don’t just begin and end with the Polivoks, though. The Soviet Union produced a whole host of electronic equipment until its collapse: synths, keyboards, drum machines, rhythm boxes, vocoders, and even electro-bayans (electronic accordions), which have a long history in Eastern Europe. These were all made in different factories across the union, in many different countries, and many brands were produced as a result.

The Zhitomir factory, for example, built Estradins and (in Vilnius) Electronikas in the mid-80s. However, the quality and sound of these machines did (and does) vary rarely stand up to a Polivoks on the best

of days.

The Polivoks had the advantage of voltage-controlled schematics, giving them a Moog-like sound. It was the kind of tone Soviet musicians wanted to emulate because of Western pop music, which began to seep into the Soviet Union from the 1960s onwards. Yet even the Polivoks didn’t sell well due to how expensive they were and how poor the average people were in the USSR.

Other notable Russian synths include the Aelita, a monophonic machine made in the Murom plant. They’re excellent machines if you can get a one in good working order. They have three oscillators and many great effects such as frequency vibrato, attack, decay, etc, which make them sound fairly contemporary – they wouldn’t be out of place in a Chvrches or Haim song.

Other great machines include the Alisa synths, made in the Luberetskiy factory. The 1377 and 1387 models are capable of some brilliant sounds, perfect for using as effects modules. They are similar to the Sequential Circuits Pro One and can be picked up for lower prices than the Polivoks and Aelitas as they are not as well known. However they are not as reliable as the Polivoks, and given that said Polivoks don’t have a great reputation themselves, you should, if possible, always try thoroughly before you hand over your cash…

Let There Be Drums

If you didn’t know about the USSR making synths, then it’s quite likely you don’t know about the drum machines the Union produced. Perhaps the best example of a Soviet drum machine is the UDS, a version of the Tama analogue drum unit. Sometimes named Rokton UDS and sometimes Formanta UDS, they were built at the same factories that made the Polivoks.

The only difference between them was that the Formanta UDS came with a ‘rhythm-stick’, which let you play each drum sound by pressing buttons on the neck and then striking a ball on the left. It was an unusual addition, and the supply was limited and not very popular.

While the UDS module can be connected to an electronic drum kit and played in the traditional way, it is also a powerful seven-channel analogue drum synthesizer in its own right. It has five identical channels that can be used and edited freely for bass drum, high-tom, middle-tom, low-tom, snare, and two channels for hi-hats and cymbals. Within every channel you can change trigger signal sensitivity, base tone pitch, pitch envelope time, amount of pitch modulation, noise/tone balance, filter cutoff for noise, accent amount and volume.

The synth also has a built-in beatbox with 16 patterns. The beatbox and the synthesizer are independent modules, so they can work at the same time freely. You can also tweak the generators of the beatbox patterns and switch every synthesis channel to its preset sound, or switch it in ‘synthesis’ mode and then control the channel’s parameters via eight knobs. Each channel has trigger input on a standard 1/4in mono jack for pads, and two additional inputs for pedals. It can be triggered from any other drum pads, such Roland SPDs, or from an audio source.

Like its cousin, the Polivoks, the UDS is capable of toxic and downright deadly sounds – again, very unique. Although the style of the electronic drum kit is very outdated, the look of the UDS module is pretty cool, and like most Soviet electronics, looks incredibly stylish in a live setup.

Soviet Synth Enthusiasts

Kuzmin’s Polivoks are not just for Soviet collectors or analogue hobbyists. Goldfrapp used the Polivoks on their second album Black Cherry released in 2003, and Franz Ferdinand used it throughout their album Tonight: Franz Ferdinand which was released in 2009.

The Russian synthpop band Forum is probably the best example of popular electronic music at that time from the USSR. Their song Little Islands sounds surprisingly modern and resembles early offerings from the likes of Spandau Ballet and The Human League.

And Finally…

It must be stressed that it would be wrong to call these instruments ‘Russian’, as the USSR was a union of different countries and the factories which produced different components were often scattered around all the different regions of the union.

For example, the main circuit boards might have been produced in Ukraine, the keys\racks\boxes in Georgia and finally all was this assembled in Russia or vice versa. However, after the dissolution of the USSR during December 1991 anyone could buy any equipment of any brand, and that is why all those factories stopped, putting an end to these brilliant maverick machines.

Essentially, they just couldn’t compete with Rolands, Korgs and other Western ‘monsters’ that they had emulated. The Elektronika EM-25, for example, could be considered the ‘Soviet’ Roland Juno – it even looks the same – but it just can’t compare to the original’s complexity and sound.

So with the purchase of a Soviet machine you’ll never have the nice creamy tones of the Moogs and Rolands of this world, but what you will get is a whole new beast entirely, and that’s something well worth exploring to expand your sonic horizons (eastward, of course).