Still Hunky Dory – Ken Scott Interview

Ken Scott is a producer and engineer who needs little introduction. The man who engineered The Beatles and produced Ziggy Stardust among many others has recently taken part in a new lecture series at Abbey Road studios (read our review in this months’s mag) Before the lecture series began Andy Price sat down for a […]

Ken Scott is a producer and engineer who needs little introduction. The man who engineered The Beatles and produced Ziggy Stardust among many others has recently taken part in a new lecture series at Abbey Road studios (read our review in this months’s mag) Before the lecture series began Andy Price sat down for a chat with a genuine studio icon…

Legendary producer and engineer Ken Scott has had a long, highly accomplished career which began at the age of 16 and has spanned for more than 40 years, working with the likes of David Bowie, Elton John, Lou Reed, Pink Floyd, Procul Harum and The Beatles. His vast range of studio experience is to be one of the subjects of a new lecture series at Abbey Road. The talks will explore the evolution of recording techniques and equipment that were pioneered at the studios and Ken will be on-hand to share his memories of working with some of the most important artists in music history. We caught up with Ken to chat about these new lectures and to learn more about the recording of some of the greatest records of all time…

MusicTech: You’ve worked with some of the greatest artists in music history, was it a deliberate choice to work with those artists that you considered to be ahead of the curve musically?

Ken Scott: Some of it was. Obviously I was thrown in at the deep end by being an engineer with The Beatles which was just pure luck, so from then on really, having that on the top of my resume made everything else a lot easier. With Bowie I’d done a couple of albums with him as an engineer with Tony Visconti producing and one day David said that he was going to produce his own album but wasn’t quite sure if he was capable of it, so he sought me out and asked if I’d like to co-produce with him.

Of course I had no idea that record (which became 1971’s classic Hunky Dory) would finish up being as good and accepted as it was. I loved working with him and the music he was making at that time. That’s much the same all the way along the line really, with all the artists I’ve worked with. But I never tried to stay in front of the curve. People came to me and if I liked the music then we’d work together.

MT: How do you think the role of a studio engineer has changed since you began all those years ago? And how does mixing digitally compare with working in the analogue-sphere?

KS: Well I still do it exactly the same way – I like the hands-on approach. When I mix it has to be through an analogue board, although I do use Pro Tools to record. I use the same old analogue techniques and gear to mix – I look at Pro Tools very much as a tape machine. I use very few plug-ins. If I’m going to use anything then I prefer to use hardware, but I generally don’t use that many effects. In this day and age I have the ability to do so much to every single track – the possibilities are endless so I try and keep it all very simple.

MT: Is there one particular record that you’ve worked on that you’re most proud of or enjoyed working most?

KS: Not really, there are too many for different reasons. Obviously it was great working with The Beatles. The two tracks that I am exceedingly proud of are A Salty Dog by Procol Harum and A Walk On The Wild Side by Lou Reed, for whatever reason I would not change a single thing about either of those track.

Ken Scott started working in studios at just 16 years of age

MT: Working with The Beatles at Abbey Road at a time when they were pushing the envelope creatively must have been really exciting. Did you realise that the work you were helping to create would endure for such a long time?

KS: Absolutely not! We would have laughed in your face if you’d said ‘we’ll be asking questions about this in 50 years time’. We had no idea. Because of that it wasn’t all that memorable to us, it was all just another day in the office – we didn’t know we were making history. People are always craving for stories about those times and it’s often quite difficult to remember.

MT: You’re currently preparing for an upcoming lecture series at Abbey Road Studios, Could you tell us a bit about the lectures?

KS: Well it’s something that really started a couple of years ago with the writers of Recording The Beatles, Brian Kehew and Kevin Ryan. I got to know them through the writing of the book. They interviewed me as they did almost every other person that worked at Abbey Road it seems! They managed to put together such an incredible book that covered the history of Abbey Road. They know more about that studio than anyone who’s ever worked there. So EMI and Abbey Road asked them a couple of years ago to give a series of lectures on Abbey Road’s long history.

I was lucky enough to go to one of these talks and found it absolutely fascinating. What they managed to dig up photographically, video-wise and equipment wise was truly amazing – so this year Abbey Road wanted to really up the ante so they asked me to join in as well. The way I see it is that these talks are something for both fans and for techies.

I’m leaving the more technical aspects to them as they wheel out the old gear and display how it was used and compare the technology they had back in the 60s with modern day plug-ins. I’m more there to tell stories about what it was actually like because it was such an important and incredible time. So much of what went on then has been forgotten and I’ve got this belief that I need to get across what it was really like and hopefully convince future artists to work back in a similar way to the way we used to work, to put some more heart and soul into it as opposed to the coldness that there is today.

MT: So has Abbey Road really changed all that much – how different is it today to what it used to be like?

KS: Well as a training situation, starting off at Abbey Road looking back in hindsight was absolutely incredible. I can’t conceive of a better training than I got there. Being able to sit there with seven of the top recording engineers in the world at that point and see how they placed mics etc, I learned massively from all seven of them. Starting my career working with perhaps the most experimental band in the world at that point – The Beatles – there were really no limits for me. I could experiment with different mics, different studio set-ups and there were no time pressures on us at all.

I’m sure working at Abbey Road today is similar to the way it used to be but in general there’s less eclecticism in music these days. You could spend the morning recording a classical piece, in the afternoon a dance band and then in the evening Pink Floyd – it was all so mixed up. Whereas today it seems very much that if a studio has a hit with a heavy metal album then for the next two years all they’ll record is heavy metal bands and so young engineers won’t be receiving the same overall training. I have this problem with radio as well, it has become so ‘genre orientated’ that you get people who, say are into rap, and so just listen to rap and nothing else. Genres are becoming stagnant.

Ken prefers to use hardware over plug-in effects but doesn’t use too many unnatural effects anyway

MT: I suppose The Beatles were pioneers of incorporating different genres into their songs?

KS: A lot of that comes from the way we grew up and really just how bad the radio was in England at that time. We had three stations. We had to endure such a lot of crap before we could hear something we actually liked. In the evening we might get to pick up Radio Luxembourg but that was only if the weather was good. We had to absorb lots of different types of music and so we developed that ability to recall elements from a vast range of genres when we needed them. Bowie was great at that as well.

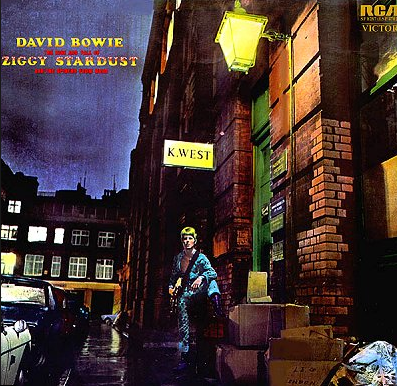

MT: Speaking of Bowie, The Rise And Fall of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars is arguably the most significant record of Bowie’s career. Can you remember a little about its production?

KS: As far as I was concerned it was the follow up to Hunky Dory. There was never any discussion about Ziggy being a concept album. There are some tracks on there that definitely fit together but as a total overall concept album I don’t see it.

Perhaps David Bowie’s most important album (certainly in the UK) The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust was one of several classic Bowie albums produced by Ken Scott

We recorded Ziggy at Trident Studios, which meant I could wear jeans and have long hair! It was a new studio – the owners of the place were only slightly older than me and so it had a totally different atmosphere to Abbey Road. Musicians would come and hang out there, it had that kind of a vibe to it.

In terms of the gear we used back on Ziggy, it was all completely recorded and mixed on Sound Techniques boards, the outboard gear was LA-2A limiters, an EMT plate to create the reverb. Mics were generally for a lot of stuff Neumann 67’s

MT: How involved in the creative process do you tend to be and likewise do artists collaborate with you on getting the production right?

KS: Oh it’s always collaborative, it doesn’t matter who I’m working with. I learnt from George Martin that talent is supposed to create and so the best thing you can do as a producer is to allow the artists to think, write and play but know that you can steer them back onto the right path if they go a bit too far afield.

MT: You must have experienced firsthand problematic creative differences, especially in the days engineering The Beatles on The White Album?

KS: I’ve worked on two week projects where at some point or another someone will loose their temper. Tension is part of creativity and it will always happen. So spending as long as we did back on The White Album – close to six months – it happened several times. So yeah there was animosity from time to time. But overall things were pretty amazing. Much has been written about their friction during these later years but I just remember them jamming and playing together all the time. There was work going on in different studios but that was because we had to keep working hard to get things done and to try and finish the record.

Although you had to be very careful about what you said to them because sometimes they could take things meant in jest seriously, I made a joke to John Lennon one day about recording in this tiny little closet-room by the side of number 2 control room, when I mentioned it he just looked over, stared at it and didn’t say anything. Then the next day he came in and said “Right we’re going to record a new number, it’s called Yer Blues and we’re going to do it in there” and he pointed to the small room. That track was recorded in there, all completely live with no separation between anything. You can imagine how much spill there was with them all just in this tiny room.

MT: How close was your working relationship with Sir George Martin?

KS: Oh George was a genius. There were times when I didn’t quite know what he was doing. I would think ‘he’s just sitting there doing nothing’ and didn’t understand that he was leaving talent to create. So I didn’t realise that I was learning from him all the time. There was one point at the end of a 24-hour session where he pulled me to one side and said ‘Ken, I don’t want you to take this personally but I don’t think this album is going to win a Grammy, but it has nothing to do with your work on it’. He was so fatherly and didn’t want me to think it was anything I’d done.

Thanks very much Ken – Read our feature on the Abbey Road talks in the latest MusicTech magazine.