Ten Minute Master: British EQ Demystified

We have noticed that a growing number of equipment manufacturers of late have begun to use the term ‘British EQ’ in their product descriptions. It’s undeniably evocative, but what does it actually mean? Huw Price attempts to find out… Names such as Neve, Helios and Trident are as familiar to today’s recordists as they ever […]

We have noticed that a growing number of equipment manufacturers of late have begun to use the term ‘British EQ’ in their product descriptions. It’s undeniably evocative, but what does it actually mean? Huw Price attempts to find out…

Names such as Neve, Helios and Trident are as familiar to today’s recordists as they ever were – albeit in the virtual form of digital plug-ins. But does ‘British EQ’ mean something specific, or is it just a convenient and effective marketing term? Behringer is one of the manufacturers currently using it – a company founded in Germany but with production based in China.

British equalisers feature on some of Behringer’s mixing consoles and the company’s website attempts to explain what this means: “The EQs on British consoles from the 60s and 70s are…kind, gentle and, above all, musical.” Some who have used Neve EQ modules may recognise this description, but those whose experience of vintage British equalisers is confined to lesser desks may find it hard to relate to.

But doesn’t every manufacturer like to describe their equalisers as ‘musical’? It’s surely fair to say that Behringer’s description could also be applied to Pultecs, APIs and Klein & Hummels. To bring us closer to an understanding of ‘British EQ’ we asked some experts for some technical insights rather than subjective opinions.

Expert Evaluation

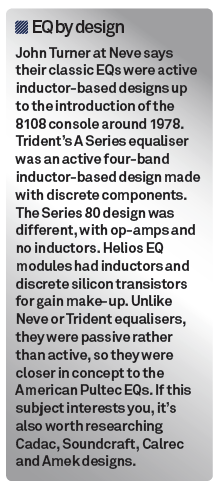

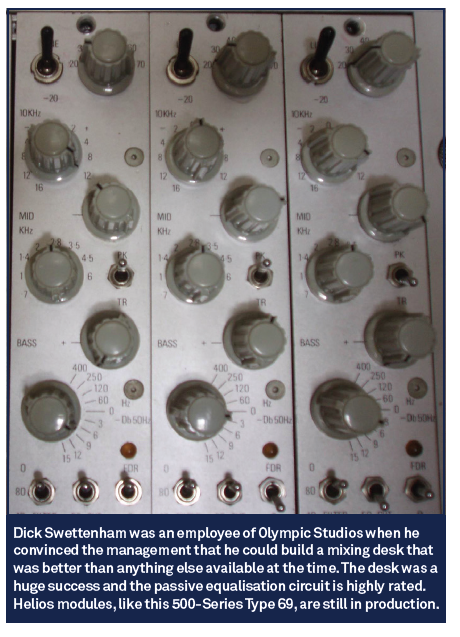

Vic Keary of Thermionic Culture seemed nonplussed by the phrase ‘British EQ’. If there was any design similarity between the equalisers made by EMI, Neve, Trident and SSL, he felt it could be the Baxandall tone stack. Even so, Vic pointed out that Helios EQ was designed differently and was better in some ways.

John Oram has been described as ‘the father of British EQ’ – a contentious title that has caused upset in the UK. Oram trained with and was influenced by Dick Denny at Vox amplifiers. Musician Dick wasn’t particularly interested in the mathematical approach of Peter Baxandall and preferred to mix-and-match components until he achieved a sound he liked.

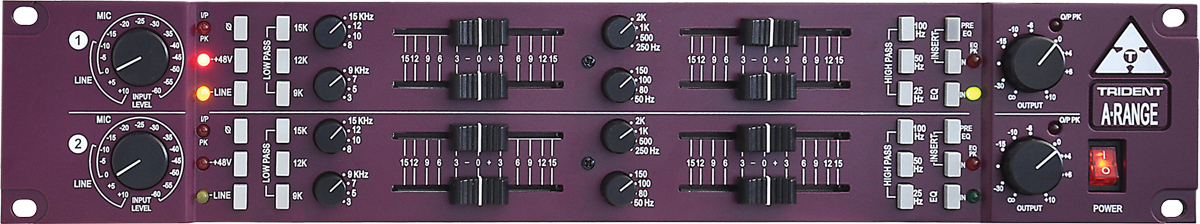

Only 13 Trident A consoles were made, so original models are scarce and very valuable. This reissue has authentic faders for the boosts and cuts and a combination of active shelf and bell (parametric) filters.

Oram described how Denny also suffered from hearing loss, so to compensate he tended to prefer sounds that were quite bright and sharp. Oram described the method as ‘empirical design’ and it certainly ties in with accounts of how the first Trident desks were created. Oram eventually joined Trident and brought his style of circuit design and sound characteristics to the later TSM and Series 80 consoles.

Oram also noted that Rupert Neve began his career in the broadcast industry. Broadcast studios of the day demanded very high technical standards, with equipment judged by linearity and low distortion. John Turner at AMS/Neve confirmed that these were guiding principles for Rupert Neve.

Interestingly, Oram does not share Neve’s sensibilities, preferring to approach circuit design from a musical rather than purely technical standpoint. Since the Neve and Trident brands are equally synonymous with ‘British EQ’, you have to wonder about the whole thing.

UK to USA

Even the father of ‘British EQ’ feels it’s a spurious term. Oram recalls people started using it in the 60s to account for differences in the sound quality of British and US recordings. Some observed that the US sound was clearer and cleaner, while UK studios were making dirtier-sounding recordings with more pronounced midrange.

Sound engineering debates tend to gloss over any contribution the musicians themselves might have made – while British bands were trying hard to capture the primal and raw vibe of Chicago blues, US groups were churning out good vibrations.

You may find it illuminating to check out some footage of Otis Reading with Booker T and the MGs on tour in Europe during the mid-60s. Playing through a rented Marshall backline, they almost sound like a different band. The typically mid-scooped Fender amp sound is replaced by the full-throated midrange of cranked-up Marshall amps and Celestion speakers. With equipment like that, it’s no wonder that British bands sounded fatter (desk EQ notwithstanding).

Perhaps the approach of British engineers rather than the equipment itself had a lot to do with the sound. All EQs create distortion and phase-shift to some extent; if two brands of equaliser are being used subtly to make minor adjustments, the differences between them will be less apparent than when heavy EQ is being applied.

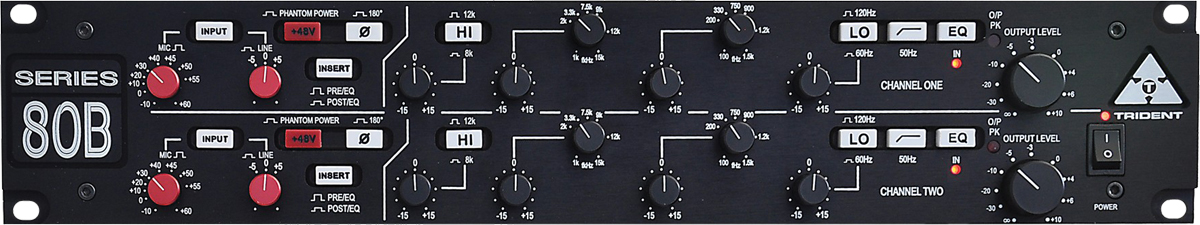

Many regard Trident’s late 70s Series 80 as a great console; however, there were no inductors and op-amps had replaced the discrete transistors. When people wax lyrical about Trident equalisers, you should ask which one they’re referring to. The Series 80 pictured below is a reissue.

Breaking the Rules

The term ‘equalisation’ indicates that it was originally designed to ‘correct’ the sound by levelling out frequency response. Could it be that British engineers were more inclined to break the rules and use equalisers creatively to sculpt sounds? Were the British simply more ‘rock n’ roll’ than their American counterparts?

Consider all the legendary British engineers and producers who went on to carve out stellar careers in the US – presumably they were employed to give US bands a British sound, but it’s highly unlikely that they travelled between US studios carrying racks of British equalisers. British audio equipment was therefore clearly not a prerequisite for the British sound.

Perhaps the ‘British sound’ was actually an aesthetic rather than a technical phenomenon, based on the way studio guys were trained and the way they felt music should sound. Rather than accept the technical limitations of their gear, they would push it to get the results they wanted. When analogue audio gear is made to operate at the extremes, it tends to sound characterful.

It’s worth noting that Abbey Road’s in-house technicians designed their own equalisers for the legendary Redd mixing desks. Based on American-made Pultecs, they were combined with V Series preamps from Siemens in Germany and US-made Fairchild and Altec compressors. Audio in the quintessential British studio typically followed a multinational signal path.

The likes of Glyn and Andy Johns, Eddie Kramer and Roy Thomas Baker started out in British studios, so it’s inevitable that people attributed the sound of their early records to the gear they were using – and to the equalisers in particular.

A lot of British equipment ended up being installed in US studios and some American engineers eventually adopted a more British approach because that’s what the record companies demanded. The lines have been blurred ever since.

Verdict

Engineers with experience of classic equipment might say that ‘British EQ’ is really about fat and up-front midrange, but the American records had better bass and extended treble. It could have been the equalisers or the working methods, but it’s more likely that achieving a ‘British sound’ required a bit of both.

With Neve shooting for technical excellence, Trident prioritising vibe and Helios utilising a passive design, the big three were quite different in concept and construction. Ultimately, we would have to conclude that ‘British EQ’ actually means different things to different people depending on what they want to believe – and, on occasion, what they’re trying to sell…