Ulrich Schnauss Interview

Andy Jones speaks with the master of shoe-gazing electronica and, somewhat surprisingly, unearths a veritable museum of music technology along the way. Over the last decade, Ulrich Schnauss has become one of the biggest names in electronic music circles thanks to some intoxicatingly atmospheric productions that display somewhat opposing characteristics, being both melancholic yet euphoric, […]

Andy Jones speaks with the master of shoe-gazing electronica and, somewhat surprisingly, unearths a veritable museum of music technology along the way.

Over the last decade, Ulrich Schnauss has become one of the biggest names in electronic music circles thanks to some intoxicatingly atmospheric productions that display somewhat opposing characteristics, being both melancholic yet euphoric, downbeat yet uplifting. His tunes have ensnared an increasing number of chin-stroking fans and, once bitten, you’ll find it hard not to hoover up the man’s complete output. And when did that last happen to you? Indeed, I have to admit that his first two albums – Far Away Trains Passing By and A Strangely Isolated Place, plus a couple of outstanding tracks on Blue Skied And Clear: A Morr Music Compilation – remain the most-played bodies of work in my iTunes collection and I have the stats to prove it.

Why? Simply because Ulrich Schnauss came along at exactly the right point in the history of electronic music and gave it a much needed shot in the arm. While many at the time were trying to push the boundaries of sound and what your ears could handle, he booted up Logic, whispered a quick ‘calm down everybody’ and went back to melody, oh sweet melody, and the sound of the synth in full flow. And what tunes.

When he hits his stride – like on the tracks Wherever You Are, Nobody’s Home and A Letter From Home – you simply want to hit ‘loop’. Schnauss was always, to my mind anyway, part of an incredible movement of Berlin-based musicians who, at the start of this century, took the laptop and shook it up a lot, creating music in a wide variety of genres which some incredibly lazy journalists of the time (uh hum) labelled ‘laptronica’. But on a visit to the producer at his London-based residence it’s time for a few of those preconceptions to be blown away. I expected a laptop – and I got one. What I didn’t expect was what it would be surrounded by…

Waldorf Wave: “It’s another one that I can’t move, and is usually considered as the ultimate wavetable synth. I was lucky as I bought two of them in a very bad state but sent them to a technician in Germany who had previously worked for Waldorf and out of the two of them he managed to get this one working.”

If Carlsberg Made Classic Recording Studios…

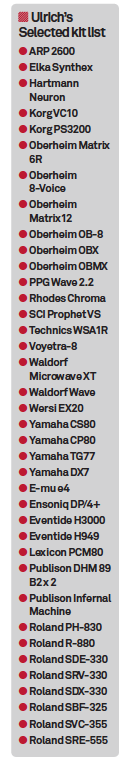

Entering his studio is a shock to say the least. Here lies an absolute classic Oberheim 8-Voice synth, and there’s one of only 25 controllers for the Yamaha DX7 ever made. Behind me stands an Elka Synthex sitting above a Rhodes Chroma. And over there, just underneath that bright Waldorf Wave, in a kind of lean-to synth storage area, a Memory Moog sits next to a Hartmann Neuron. There’s an Ensoniq Fizmo down there, too. And a Prophet VS. Like you do… And that’s just the half of it. Walking around the room we’re suddenly in Part 2 of the studio. A huge pile of classic effects are all plumbed into a mixer and patchbay. And it’s nice to see ‘digital’ taking pride of place alongside ‘classic analogue’ with notable inclusions like a Roland V-Synth and a Technics WSA-1 (remember that?).

It’s like a living and breathing classic gear museum, the sort of place you could lose years in just plumbing one thing into another to hear what happens. Which is exactly what Schnauss has been doing for the last couple of decades. So, not exactly ‘everything done on a laptop’ then… So what of that famous Berlin laptop scene? “Actually, a lot of them used hardware like this,” laughs Schnauss. “It was a bit of a myth that we all used just laptops.”

Drum n Bass to Electronica

Schnauss grew up in a small town called Kiel on the Baltic Sea between Hamburg and Denmark. He developed an interest in electronic music around the time of acid house. “A couple of years later I bought my first keyboard and sampler and eventually found some other people who were into electronic music and we put our gear together into a studio.” Schnauss’ first productions were drum n bass, but in 2000 he made a very conscious decision to turn his back on that genre and follow his heart: “I wanted to start doing more song-writing based electronica,” says Schnauss. “I was friends with the guy who ran [influential label] City Centre Offices and in 2001 they released the first music under my own name, which was the album Far Away Trains Passing By. “It was the first truly successful thing I’ve ever done, a real breakthrough,” he continues. “It was weird as it was born out of a disillusionment with what I was doing. I had been trying to get somewhere with the drum n bass and other stuff I’d done in the 90s.

So I thought, ‘I’m just going to do what I want to do’ and not really care whether DJs are going to play it. Far Away Trains came out and all of a sudden it became really successful, which was quite bizarre.” The album was successful in the UK and live appearances at festivals like The Big Chill helped increase the fan base. The follow-up, A Strangely Isolated Place, became big enough to attract the attention of Domino Records, which picked up both albums in 2004 and pushed them in the US.

This led to syncs on shows such as CSI and suddenly Schnauss’ profile Stateside was as significant as it was in the UK. Since then he has released the reverb-washed Goodbye and his fourth album, A Long Way To Fall. Some say it’s very different, but it’s all you might expect and more, but we’ll come to that later. First let’s talk about this amazing collection of gear…

“These are all more lightweight synths that I can carry – a bit different from the Chroma and Synthex – so when I want to use one I just take it out. There’s stuff from right across the board, liek the Ensoniq Fizmo, which is quite an interesting digital waveform synth. Next to it there is the PPG Wave, another digital classic, then there is the Oberheim OB-8, which is probably one of my most used instruments. The Memory Moog is a nice polyphonic synth from the 80’s

Dust and Chrome

“I bought much of this stuff when it was affordable,” Ulrich says. “If I was to get it now with the same amount of money I spent then I’d probably only be able to afford 20 per cent of what you see as prices have exploded in such an insane way.” So out of everything we’ve seen, which would Ulrich cite as his favourites? In fact, choose just five… “Actually I could probably just choose two,” he laughs. “Your favourites are your favourites – simple! Some instruments have remained my core, like the Oberheim OB-8 which is audible throughout all of my records, but my all-time favourite synth is the Voyetra-8. It’s an amazing instrument – it sounds so characterful and so different from anything else of the time.

And I like it for simple technical reasons, too. Unlike lots of other synths from that generation it has SSM filters with an almost creamy sound which is interesting. “In terms of effects units,” he continues, “I really like the Publison DHM 89 B2 unit. It’s like a really early pitch-shifter/looper. It’s from the late 70s but it’s digital and because it’s such early digital technology it completely destroys the input signal, but in a great way. I use two in a chain and quite often I play piano stuff into it and then loop the first one and let it run for a bit until more mistakes appear.

Then I loop the second one and end up with really nice droney atmospheres; I now have a whole library of them.” And as I’ve pointed out, there’s no digital snobbery here… “I think digital is great,” Schnauss confirms. “I get really sick of these analogue-v-digital debates. Quite often people come to me at my gigs and talk about my warm analogue sounds and it’s actually the Waldorf Microwave or whatever. I think people’s perception of what a digital instrument and what an analogue synthesizer can do is very twisted and wrong. You can actually create really warm and beautiful colours with digital instruments as well.”

“This is a semi-electric piano that works a bit like an electric guitar as it has strings so you can play it when it is not amplified but also has pick-ups inside so you can plug it into a mixing desk, so it is therefore quite easy to record”

Piano Leads

So how does a typical Ulrich Schnauss track come together? “It’s always the same thing really,” he replies, being surprisingly open about his composition methods. “I sit down at the piano and improvise, sometimes for half an hour, sometimes for two hours… On a good day a theme will appear where I think ‘this is an interesting set of chords or melody that I could develop in to a song’ and then I pretty much automatically get an idea about which sounds will be suitable, so I just turn around and play that into the sequencer and start arranging layers around it.” So would he ever consider using software synths at this point to sketch out a song? “Usually I try to avoid that because if I have too many sketches flying around I will never get around to actually finishing something, so it’s nice to start something with a solid foundation. I would probably take something like the Oberheim as it has really warm, deep sounds, so if you use that to arrange some basic chords it is a good solid foundation for a track.”

And roughly how long would a typical track take from start to finish? “It’s always different,” says Schnauss. “In the quickest case it might be two or three weeks but there are one or two tracks on the new album where, after a couple of attempts, I wasn’t happy so I re-recorded them. So they probably took maybe nine months, although obviously I wasn’t working on them constantly.” With all of this gear you’d now assume that Schnauss has no need for software plug-ins, and you’d be correct, sort of… “I don’t use soft synths a lot,” he reveals, “but I do use plug-in effects as there is a lot of stuff around now that doesn’t exist as hardware. From Isolated Place onwards you can hear a lot of granular effects in my music and obviously they don’t exist as hardware. Back then I used Cycling 74’s Pluggo as it was new and a very easy way to get into granular synthesis. I really liked their interfaces as they really encouraged you to get in and play around.

Since then I’ve been looking around for interesting stuff and have been using the Reaktor user library. Unfortunately, I’ve never got around to building my own stuff – something I’d like to do – but there is just so much free stuff floating around…” That’s not to say that Schnauss hasn’t been tempted by the odd soft synth… “There are a couple out there that I find as interesting as the hardware. Xils-Lab did a couple, including a software version of the Elka Synthex. There’s one thing I always like about the Synthex and that is if you use sounds that use oscillators radically – like one is tuned to -24 and one tuned to +24 – and you use those in extreme ranges, then the sync’ing creates quite a lot of weird artefacts and mistakes, and the plug-in manages to do that. I think that is great. My problem with plug-ins before that was that they often sound pleasant and nice but lack the character of the hardware. I often like to use the hardware where it starts to go wrong, like going out of tune or aliasing or something like that.”

A Long Way To Fall

Schnauss has reportedly taken a different approach to his latest release, A Long Way To Fall, but to these ears it is still definitely him. So was there a definite attempt to shift the focus musically? “It’s always difficult to judge your own music without being biased,” Ulrich says. “Some people would probably say it doesn’t sound that different and others have already said it sounds radically different! My take on it was that I was becoming bored with certain things, like I didn’t want to drown all the synths in reverb any more and I wanted to use more percussive sounds; synth sounds where the shape is more important, not just atmospheric drones. I was also getting bored with the breakbeaty-type sounds so wanted to move away from bass/snare and use more ‘found sound-type’ of stuff, like breaking glass or footsteps or whatever.”

The album has definitely retained the Schnauss sound, but explaining what that sound actually is not easy. So let’s ask the man himself… “I try to make music which is not so much about having one lead element with the rest as a backdrop. My idea was always to create music which is almost symphonic, with all elements justifying their place and working together rather than a typical pop formula which is all about creating a backdrop for something that is really aggressively placed in the middle that you hear once and will never forget. Whether that is good advice, I doubt it! It probably reduces the commercial element and potential of your music.” “To be honest,” he continues, “I know how the effects and synths work but I am always discovering new areas of production – it seems to be an endless area.

I recently met up with some friends of mine who are well-known drum n bass producers and one thing I discovered was how important it is to brutally separate different elements in a mix. Let’s say you have a sound providing a chordal foundation to a track. You might listen to it on its own and it will be nice and warm, but in the mix it might not work and you have to brutally high-pass filter that to make space for a bass underneath. So one of the things I have been trying to incorporate over the last couple of years is that if something sounds great on its own it might not necessarily sound so great in a mix.”

And what about advice to electronic music producers? Is there a way to make your music work for you financially? “That is a really difficult question,” says Schnauss. “The reason I can survive is clearly sync work – I could not have survived just from record sales or playing live. For anyone who produces instrumental music it is a good idea to invest energy into trying to get syncs. Rather than going for conventional publishing deals, people these days look to sign with these specialist agencies in America who deal with syncs and I’d say that is a good thing to do.”

Rear view of Ulrich’s main rack, conveniently located close to his central working area

Are We Happy?

As we near the conclusion of the interview, let’s deal with the conflict in the Schnauss sound. How can it be both melancholic and uplifting? “I am not necessarily the most happy or optimistic person on the planet – who is? So when I write music I do it to escape, so there are both elements in my music: melancholy, which is probably from the situation I am in when making music, but there is also a hopeful utopian element which describes the state that I would like to be in or the state the music is trying to describe.”

Ulrich takes a break from perusing his vast vinyl collection

And finally, any remaining ambitions? “Yes, of course, otherwise I’d probably just stop and shoot myself or whatever! I think I’m very far away from achieving what I want to achieve. Everything you release is just a snapshot and then a month later you are already unhappy with some elements. Even with the latest album – if I started on it again today it would be quite different. It’s all a process, but that is also what is good about it. There’s nothing more boring than perfection!”