The core principles of songwriting

In the pages of MusicTech we tend to focus mainly on the technology, gear and the intricacies of music production. What we spend relatively less time talking about is the fundamental core of everything we do, regardless of genre; and that’s the compositional process itself. In a linked series of features, we explore approaches to making songs and tracks with practical guidance and experienced industry insight, as well as taking a look at the modern world of professional songwriting and the ever-growing interest in songwriting training.

Image: Shutterstock

In the modern world of music, it’s almost seen as a badge of honour to have an eclectic taste in myriad genres; from dance to rock to dubstep to ambient, the old days of aligning oneself to a tribe in thrall to genre are, in the main, long gone. Despite the technical differences between each (often wildly different) style of music, the central question persists: how does an artist come up with creative, musical ideas, conceive a structure and build songs that work to affect the human mind?

This process has many names – and with certain genres, the lines between composition and production are blurred. So for simplicity’s sake, we’re going to refer to this entire stage as songwriting.

In this feature, we’re going to explore how understanding the musical structures of songs and tracks can arm you as a composer, help you combat creative dead ends and potentially open your mind to the idea of developing a career as a go-to songwriter of the kind that works with world-straddling pop stars and bands.

Thinking structurally

Let’s start by thinking about just what songs are and how they’re typically assembled. Most songs in Western popular music in the traditional sense adhere to a form that is built from different sections (typically referred to as verse, chorus, bridge etc), and different assortments of the sections are referred to with letters that reflect the section types (so ‘A’ generally refers to a verse, while ‘B’ references the chorus). This then results in the popular song forms being referred to as ‘ABAB’ or ‘AAAA’, for example.

The ‘AAAA’ form (also known as the strophic form) is one of the oldest song structures, and harks back to the days of yore when folk balladeers would melodically craft lengthy, wordy tales of courtship, heroic deeds in distant lands and other concerns of the age. In effect, we have the same musical section (more often than not, the verse) repeated with different lyrics over the top-line melody (or indeed, a different top-line melody).

Despite its medieval origins, the form endures to this day and is mainly popular with acoustic singer-songwriters, though if we’re considering these forms to be broadly applicable to different genres, then the general idea is demonstrated in a great many electronic dance-music tracks, which largely maintain the same fundamental chord sequence, rhythm track and repeated lyrical or melodic ideas, with the dynamic quality coming from the addition or subtraction of instruments and tracks. Examples of the AAAA song form include Viva La Vida by Coldplay, All Along The Watchtower by Bob Dylan and With Or Without You by U2.

More popular than this traditional approach is the ABAB form, where – you guessed it – the verse gives way to a second ’B’ section (usually a chorus). Indeed, this form is more widely understood as the ‘verse/chorus/verse’ form, with most prominence being lent to the chorus.

The verse generally serves less as a focal point of the listener’s attention and builds toward the chorus, which commonly contains the song’s central melodic, lyrical or thematic hook. The chorus is often emphasised further by pre- and post-chorus sections that serve as a sort of ladder from the verse into the explosive chorus. We’re speaking here mainly of musical structure, but the lyrical content and the music should dovetail neatly at this point to form the best distillation of the theme or artistic intention of your song. This form serves the immediacy of pop music very well, with the central ear-worm of the chorus being neatly packaged and emphasised by the structure of verses around it.

These two forms are among the most popular of song-forms and their structure is broadly applicable to every genre. Other forms include:

AABA Also referred to as the ‘American Popular Song Form’, this approach was quite common in the pre-pop age (the heyday of the crooner). The structure is mainly verse based, while the B section doesn’t refer to a chorus as such, but instead a bridge section that commonly shifts the composition into a minor chord.

AAB The 12-bar blues concept fits the bill here – this ‘AAB’ description doesn’t really refer to sections at all, but articulates the movement of chords around what is typically understood as a ‘verse’ section, which largely keeps the same rhythm and melody and is a blank canvas for improvisation by lead instruments.

ABCD An ever-changing, shifting series of musical and chordal ideas which dispenses with a central hook or motif entirely. This is less popular with songwriters and more aligned with avant-garde composers and progressive music.

In the world of professional songwriting, particularly for pop acts, the ABAB form is the most widely used and songs are built-in adherence to this format. It’s not uncommon for large teams of songwriters to convene in remote locations and work together to build songs for artists. These forms merely explain the skeletal structures of songs, the musical components (ie, what chords are used, the time signature, the insertion of a top-line melody) differ for each song and are often dictated by genre conventions.

Melody maker

The central musical motif or hook is usually in the form of a top-line melody and it’s usually among the first ideas that songwriters come up with. After all, this is the part of the song that has the most impact on the listener (and if it’s ‘whistle-able’ then all the better!) More instrumental-based songwriters may start with a looped chord sequence, however, and take their time trying out different top-line melodies until they hit on the right synthesis of sound, while some focus exclusively on top-line creation.

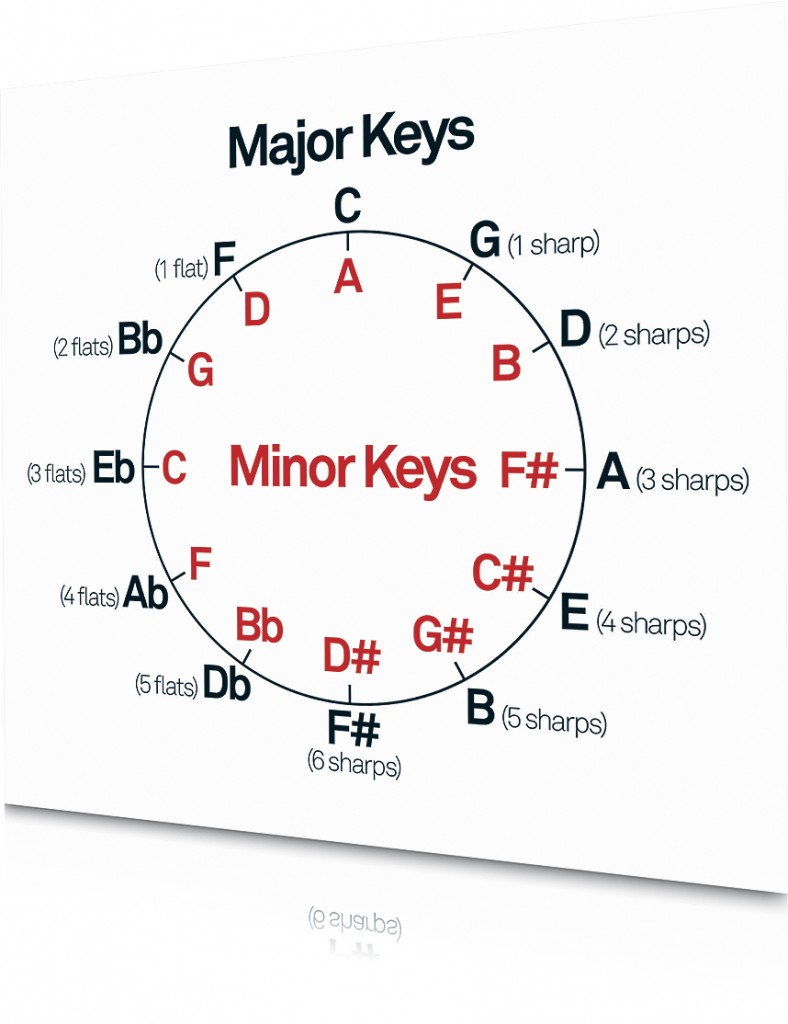

Conventionally, in a pop song, the top line is the vocal melody which is foregrounded and emphasised in the mix. On a technical level, what’s happening (or should be happening) musically is that the intervals that make up the key the song is in are being moved through in an interesting way. There isn’t really a preset route through intervals (so as long as you remain in the correct key of the song) so you’re free to enjoy exploring the millions of variations you can construct from alternating the note sequences, emphasis and speed.

A good top line should have a significant degree of movement, but also have a recognisable, fixed shape that shouldn’t vary too much.

An important thing to remember also is that this top-line hook has to be effective enough to retain itself in the listener’s brain, to make them want to hear it again, so repetition is crucial. Most pop songs have at least three instances of the top line in the chorus, while other songs take a more ‘fast food’ approach and stack up multiple hooks throughout the song that all serve as distinct top lines.

The top line doesn’t necessarily have to be the vocal melody; it can be performed on any instrument (though it helps if it is the most prominent part of the mix, so don’t have it compete with a vocal melody). Many professional songwriters specialise exclusively on the top line, as it’s so integral to the mechanics of a successful song.

Building a melody: step-by-step

1. The most simple way to approach the creation of a top-line melody is to think about the stacked notes contained in your chords. These three (or more) notes make up the triads. If you record a track of your basic chord structure and then record the notes in ascending order in a separate MIDI track, then you have a very simple, repetitive melody.

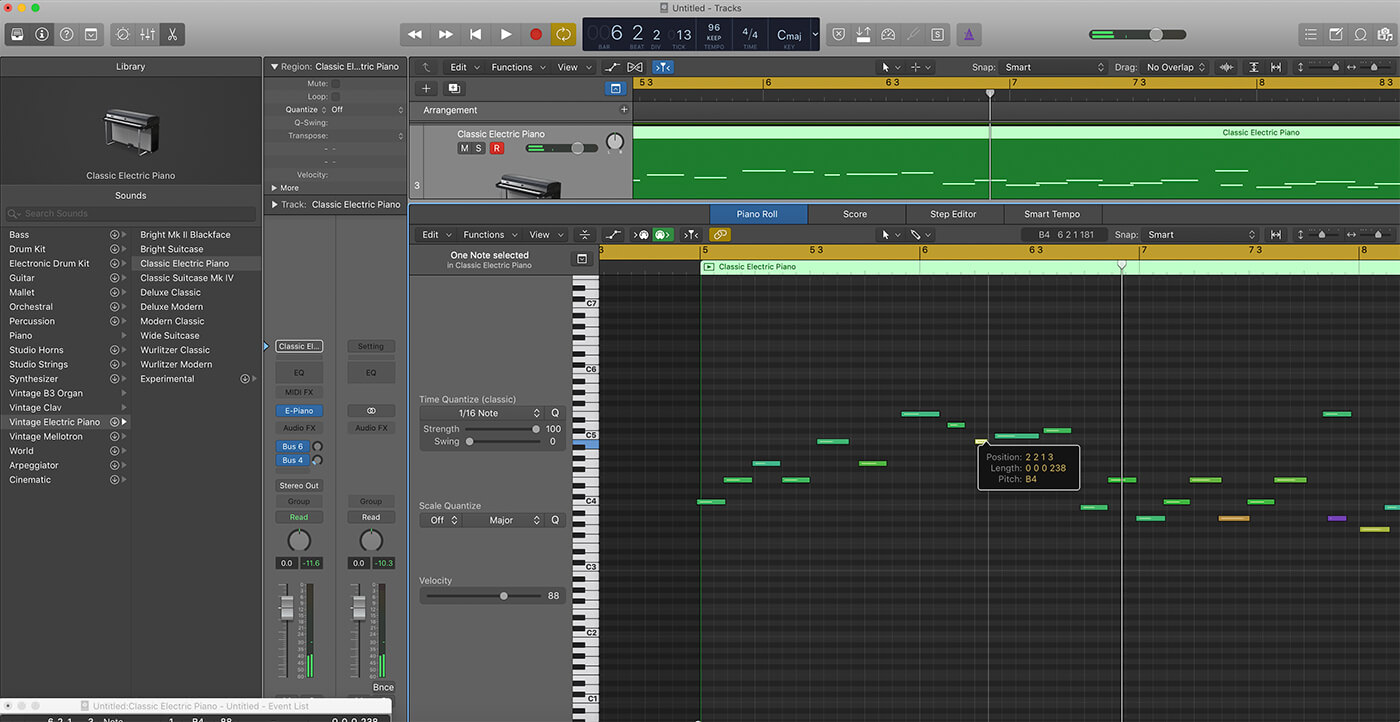

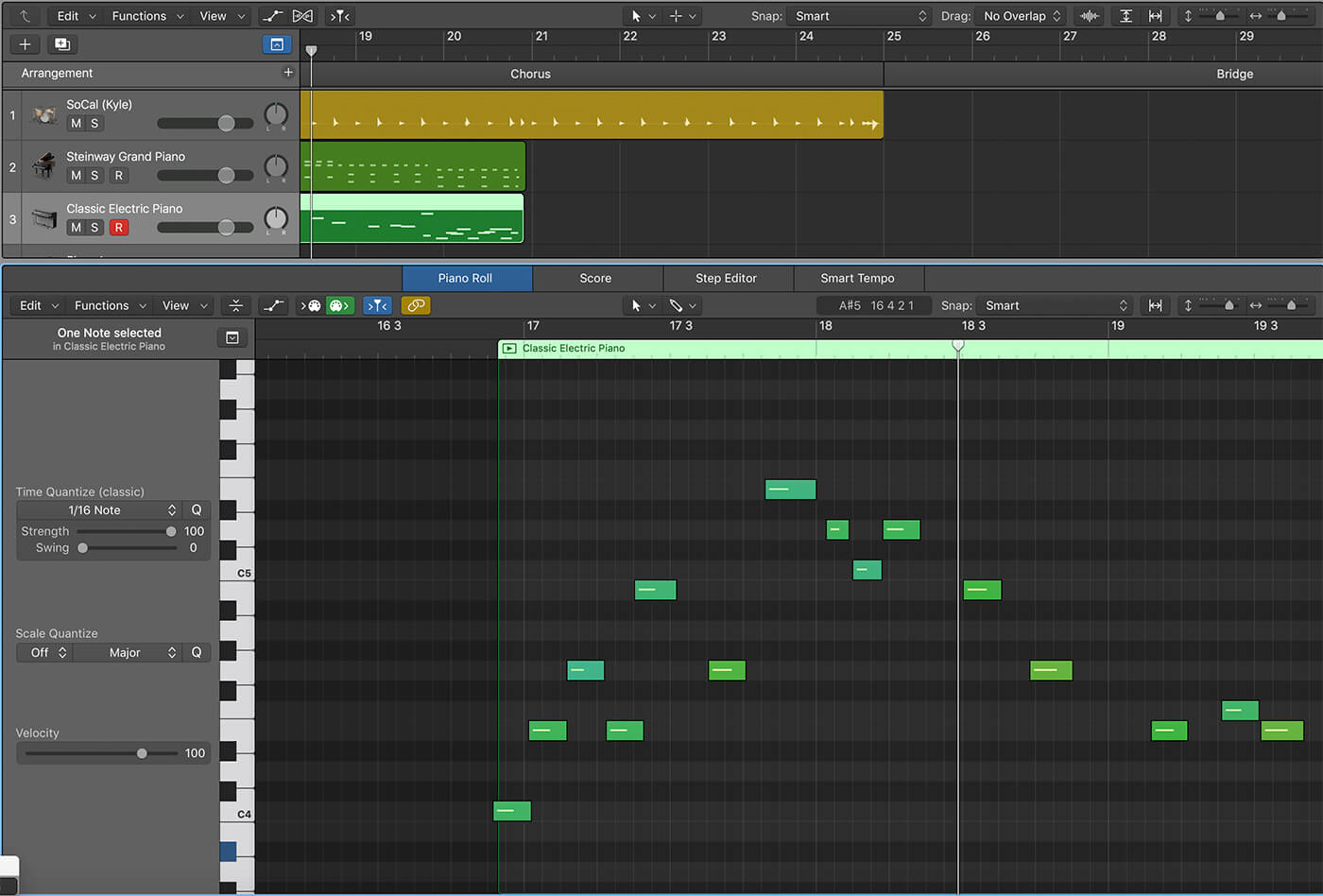

2. If you look at these notes in a MIDI editor, you can visually understand why the melodic placement of certain notes has an effect on the ear. Start removing notes from the track and adding more ‘bridging’ notes that move up and down. This top-down view can yield more interesting ideas, and you can see visually how melodic shapes are built.

3. To make the top-line melody an ear worm, it needs to sit in a central part of the song – most usually, this is the chorus. The general rule of thumb should be that the melody ascends to a higher pitch than the preceding section of the song; this dynamic lift signals to the listener that this melody is important.

4. Descending gradually from the highest note of your melody can sound far more natural than swooping around octaves. Once you’ve got a rough shape of your top line, it’s a good idea to take that melodic idea and experiment with it on an instrument, or perform it vocally. This can help refine the shape and note transitions to make it ultimately feel more natural.

Tension in the room

To recap then, the top priorities of any songwriter should be form and structure with serious thought given to the central melodic hook, the third most integral aspect when building a track is the dynamic quality. How we guide the listener through the song psychologically should be a major consideration from the get-go.

A tried-and-tested route to maximise the emotional journey of your song is by beginning your arrangement slowly and with minimal instrumentation. Here you can establish the key, structure and mood of your composition before bringing in further elements (often a rhythm track – depending on what genre you’re working in) and build towards the towering ‘peak’ of your song. This steady evolution keeps the listener hooked and rations the endorphin-release of the chorus, making boredom or overload less likely.

Understanding the power of tension is a critical concept in songwriting; building up your structure both musically and audibly to maximise the central hook is what every successful song does and if you want your song or track to resonate, then you need to consider the sonic path that you’re taking the listener on. Your music and lyrical content should work together to sell the story or theme of your song and giving the listener time and space to breathe is important.

So there are the three, we would argue, central technical considerations of songwriting. There are some more in-depth guides to the building blocks of song-craft here which have practical demonstrations and transferable techniques.

In the words of Warner Chappell’s longest-serving songwriter Paul Statham (who we speak to in-depth on page 32): “The best resource is your ears – just listen to songs and try and work out what is affecting you. What is it about a song that makes you feel the way you do? Is it the dynamics, is it the lyric, is it a weird chord inversion? Try and deconstruct the things you like, even when you’re sat on a bus or something. Try to understand what your favourite songs are doing. Once you’ve figured that out, you can apply a similar principle to your own writing, to try and make others feel the same thing.”

Preparing a personalised writing preset: step-by-step

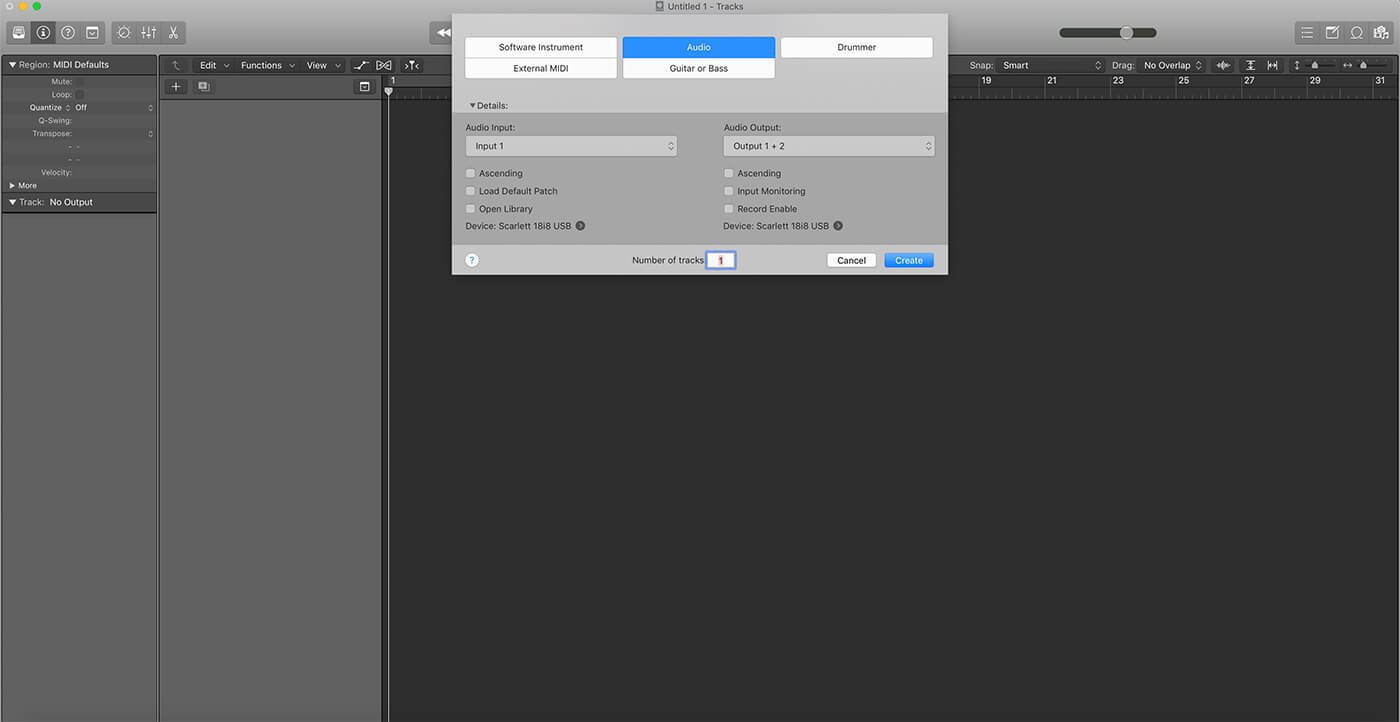

1. If your focus is going to be devoted to writing, then you need to learn to avoid getting bogged down with option paralysis. The best way to combat this is to build a time-saving, personalised template in your DAW. Logic Pro X is particularly geared towards writing and our go-to option here.

2. Firstly, open a new project and begin adding audio tracks. You’re going to need the core instruments that you use, in our case, we tend to compose basic ideas with two guitar tracks, a bass track, a vocal track, a MIDI piano track and Logic’s in-built Drummer for quick and effective rhythms.

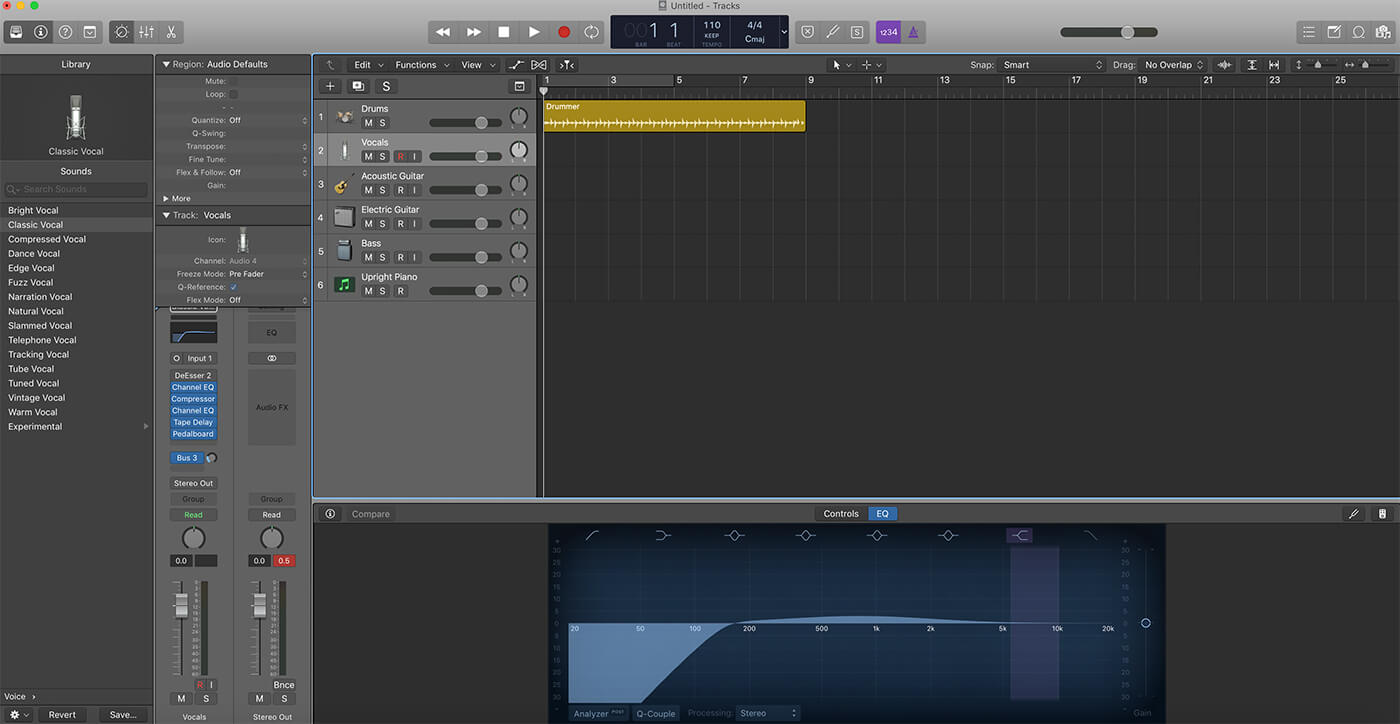

3. Make sure that each track is preset with your most commonly used effects. For example, a smattering of Logic’s Space Designer on the vocals is a must, as well as appropriate compression on each instrument. We also make sure the MIDI controller is set up for our go-to piano sound (NI’s The Gentleman) and our guitars are running through our preferred rhythm and lead chains in Guitar Rig.

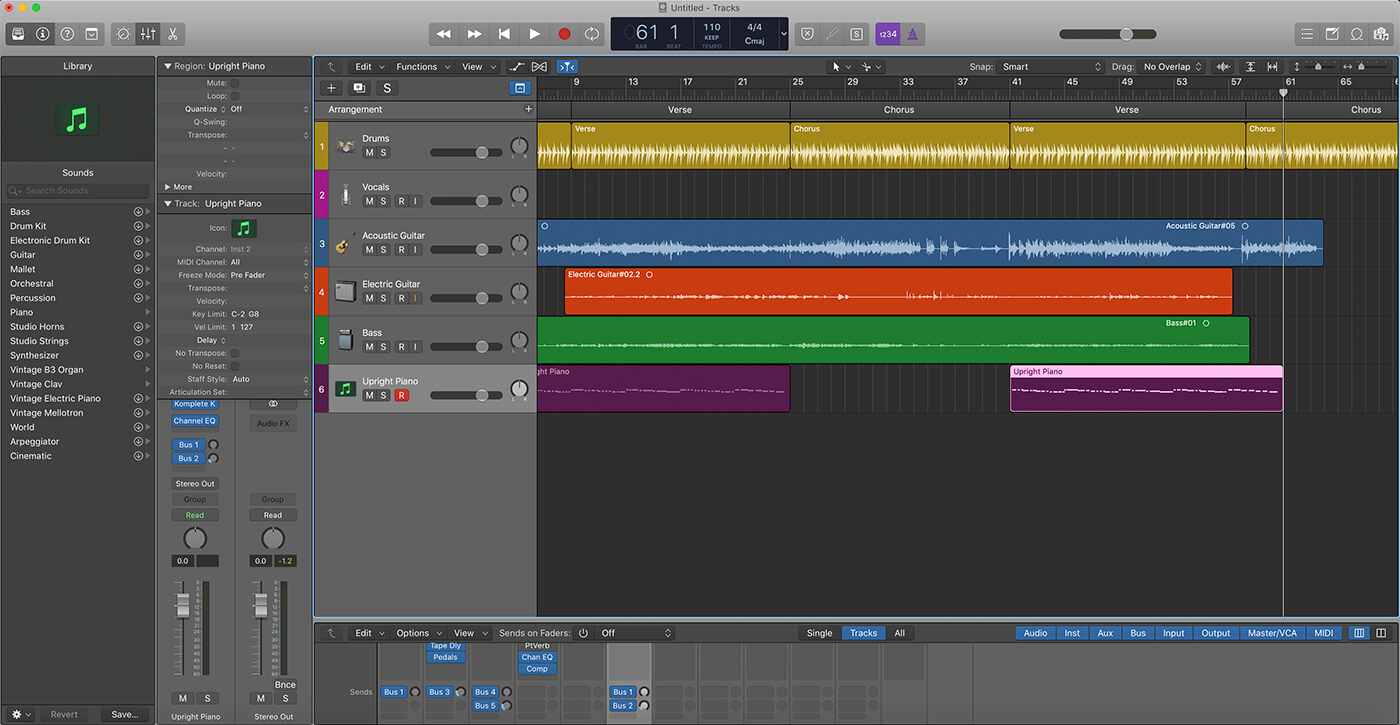

4. Using this template, start to build a typical song, perhaps one you’ve already written which consists of a basic ABAB form. Be sure to add each section of the song to the arrangement view in Logic (Track>Global Tracks>Show Arrangement View) and create a basic demo. You can modify the arrangement as you go in future demos and don’t need to stick rigidly to the template.

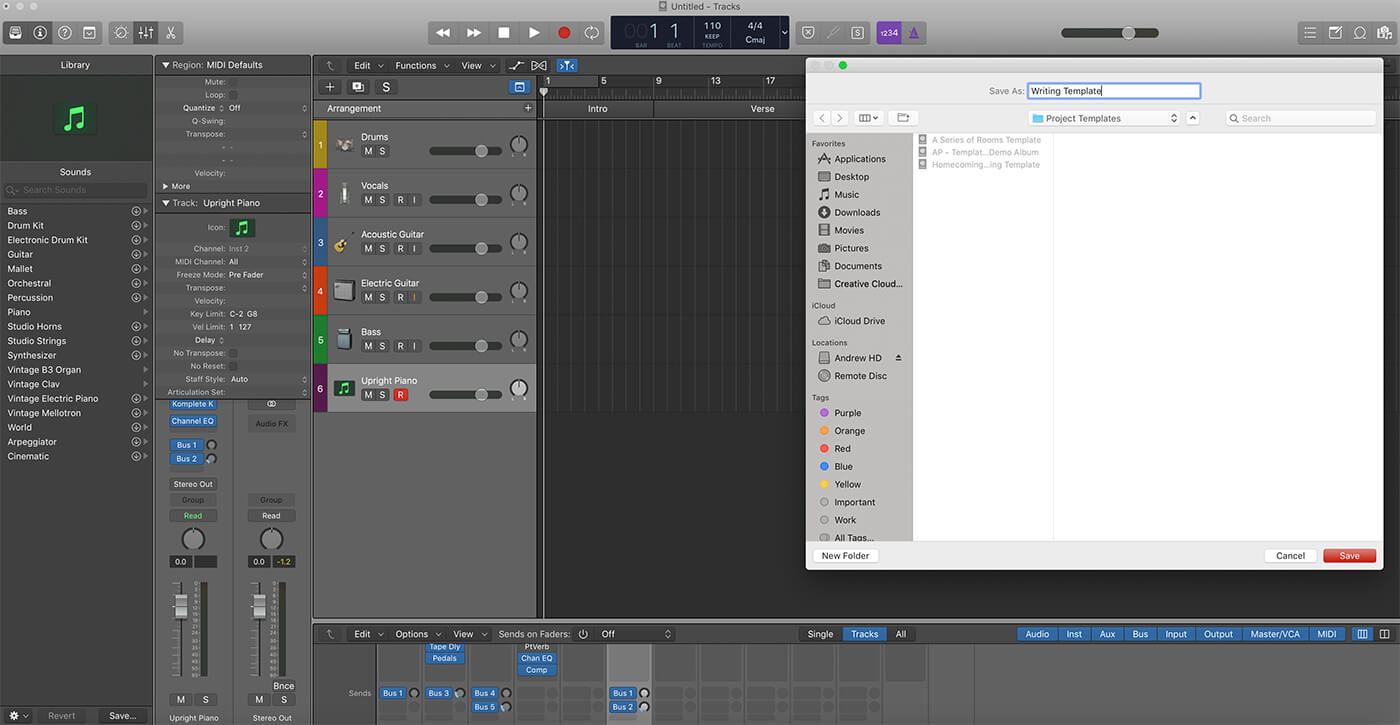

5. Once you’re confident that you have your key instruments and sounds in place for writing, then it’s time to undo your recordings to eliminate the audio and save your project as a template. Head to File>Save as Template and call your new template ‘Writing Preset’.

6. Of course, this template is just a starting point and as you go, you can add more elements and bolster your arrangement. It’s recommended to develop the arrangement and explore mixing in a new project. However, this way, you can speedily finish initial melodic and structural ideas using the restricted instrumentation of this template to maintain your writing flow.

The ground floor

So if you’ve adopted these principles, have a raft of what you believe to be effective, potential commercial smash hits, then how do you get the songs into the hands of publishers, artists and labels? Well, multi-Platinum songwriter Jez Ashurst has some advice. “I think if you want to build a career as a songwriter or a producer (or both), you need to be out there trying to find artists who are beginning their career that you can develop. That means scouring YouTube and going to gigs. If you can get in at the ground floor with them and help them develop their sound, then that’s a good way to get into the industry.

“You need to start with someone who’s pretty fresh and develop them to where they need to be, and make a whole bunch of songs with them,” Jez continues. “It’s the hardest time ever to be a songwriter who doesn’t write hit singles. In the old days, many songwriters would make a decent living, usually by co-writing say track 4 or 5 on a record. Now, success is more based on individual tracks. It’s more of a ‘feast or famine’ scenario. Streaming payments aren’t amazing, so having a radio hit can make a big difference to your royalty stream. The landscape has definitely changed.

“I think on the upside, though, the definition of a ‘single’ is changing, too. If a song goes viral, it gets streamed. It’s less easy to define these days, what a guaranteed hit single will sound like. So it’s a healthy time from that angle: you can bypass the traditional gatekeepers.”

One thing that everybody can agree on is that there’s still an unquenchable thirst for new music, new hits and the right training to forge a career in professional songwriting. In a variety of features this month, we speak to a range of individuals who are currently working in this field to understand the realities of the songwriting industry in 2019.

For more essential guides on songwriting, check here.