The history of trackers

Few music-sequencing softwares have a history as distinctive as the tracker. With the epochal program now arriving in hardware form, we trace the tracker’s lineage, from its humble 8-bit beginnings to its era-defining rave sounds.

Though trackers might look like a nightmare to the uninitiated, their ghastly visages belie a more malleable and fun-loving nature. Don’t let the cascading digits and dry UIs fool you – these things simply love to party. From Calvin Harris and Deadmau5 to Venetian Snares, many legends of electronic music have used the sequencing software to kick off, cultivate and prolong their careers, while soundtracks for pivotal video games such as 2000’s Deus Ex have made use of their distinctive traits.

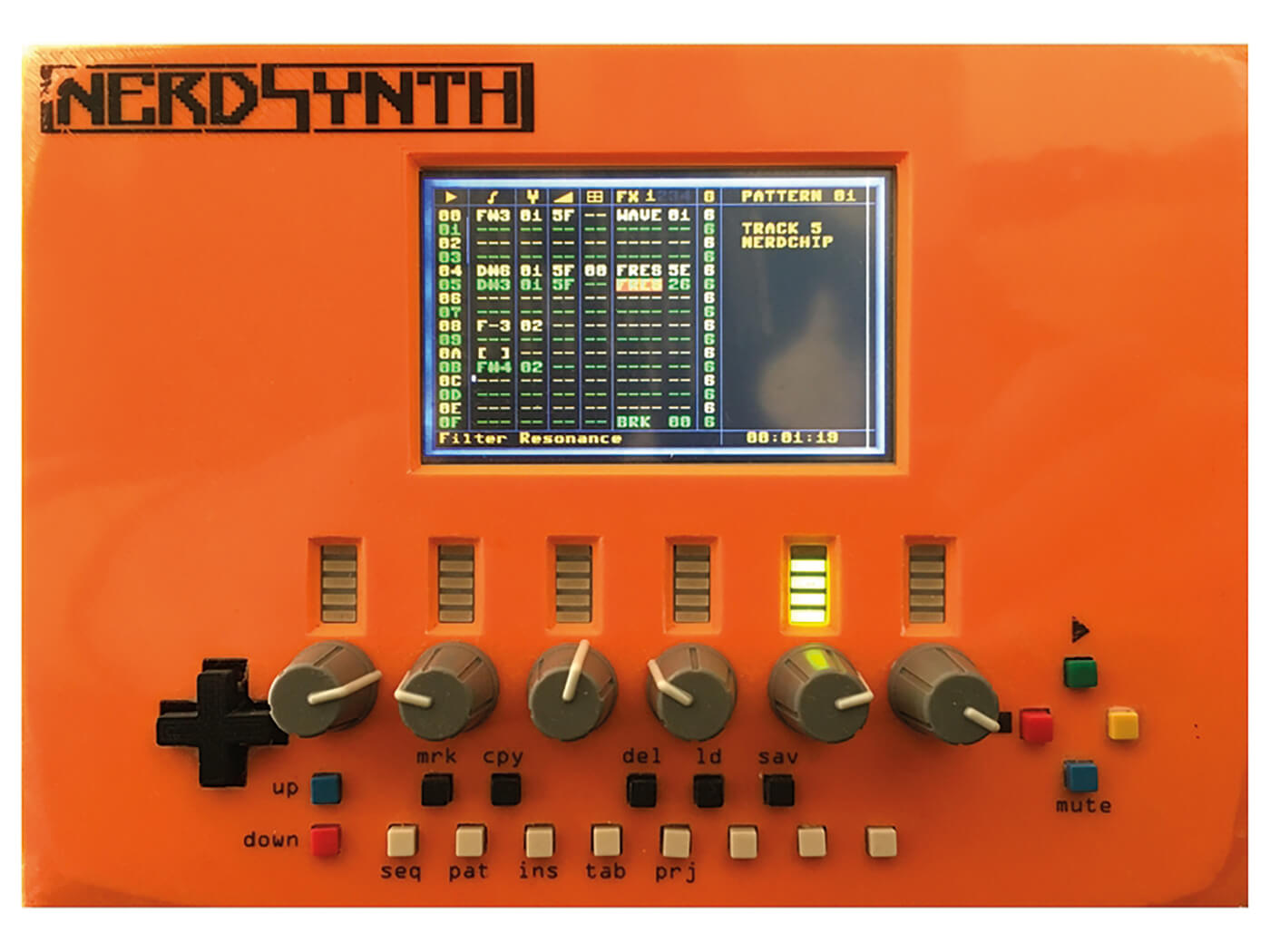

Now, more than 30 years since trackers played a vital role in democratising electronic music, the software is entering the hardware arena courtesy of the Tracker by Polish company Polyend, and the Nerdsynth from Netherlands-based XOR Electronics.

But why is this cult software going through a renaissance now? “Trackers never went away,” says MeeBlip co-founder and journalist at Create Digital Music Peter Kirn. “What makes them special is that they’re a musical interface built around the screen and computer keyboard entry. It isn’t an adaptation of some existing metaphor, like the divisions found on sheet music. Once you understand them, you can get the feeling of connecting to what’s in your brain faster. Now a tracker-maker can go create their own hardware device, which is something beyond a conventional DAW: standalone, all-in-one hardware that people actually want to use. So it’s not just a comeback for the tracker – maybe it’s their revenge.”

Aphex Twin plays back the harmonic parts from Vordhosbn, the second track from his 2001 release Drukqs, using tracker software.

Enter Paula

In the mid-1980s, computer-based music production didn’t exist in the same way it does today. Home computers were far less powerful, the era’s 8-bit machines typically limited to a few channels of synthesized tones. Things changed drastically in 1985 with the arrival of 16-bit home computers, specifically the Atari ST and Commodore Amiga. The Atari ST had built-in MIDI ports and became the de facto sequencing computer for home musicians. But, for those without MIDI hardware, it was the Amiga that would kick down the door to the world of production, thanks to its advanced audio chip Paula.

Paula was a powerful lady. Her four PCM-based audio channels meant she could play back four samples at once. They may only have been of 8-bit quality but they gave the computer a far broader tonal palette than its predecessors. Today many Amiga games, including Shadow Of The Beast, Xenon 2: Megablast and Project X, are better remembered for their soundtracks than their gameplay.

A few years later, in 1987, Amiga-based musician Karsten Obarski coded a piece of commercial software that would make composing videogame soundtracks much more convenient – and it’s from this that trackers would take their name.

![]()

With its inscrutable alphanumeric interface, Ultimate Soundtracker may have looked complicated but operating it was relatively straightforward. Each of its four vertical lanes represented an audio channel, with the vertical axis representing time. Songs were constructed from patterns, which were typically 64 lines long and constituted four bars of music. Samples were triggered by entering a note value on a lane at the desired timing. On playback, the tracker would scroll through the pattern and play the triggered samples, a bit like a digital piano roll. These four-bar patterns could be arranged into complete pieces of music by using the simple playlist editor, giving computer musicians a practical way to create immersive pieces of not inconsiderable duration.

Obarski’s software also introduced the MOD file format, which became hugely popular with videogame developers and hobbyist musicians – and on the Amiga demoscene. Demos are programs designed to demonstrate the graphical and audio capabilities of their host computer. Programmers would put their coding knowhow to use and compete to eke the most impressive results from a given piece of hardware. The subsequent demos were (and still are) exchanged at coding parties and via the internet, and many 1980s and 1990s computers still have vibrant demoscenes today.

As ever when a piece of revolutionary technology is released, the emergence of Ultimate Soundtracker saw several shareware and freeware clones follow suit, including NoiseTracker and ProTracker for Amiga, and later Scream Tracker for MS-DOS. These added new functionality to the now-established tracker formula, especially when it came to their secret weapon.

In addition to playing back samples, trackers also offered effects, accessed by entering an alphanumeric code on the line on which you wanted the effect to occur. Beginning with arpeggio and portamento, and now expanded to include volume level, timing offset and sample playback position, these were a way for tracker users to get more from their samples.

The lineage of tracker compatibility is complex but if you’d like to get lost in the grizzliest of details, click here to access a sprawling and incredibly in-depth infographic.

Dream come true

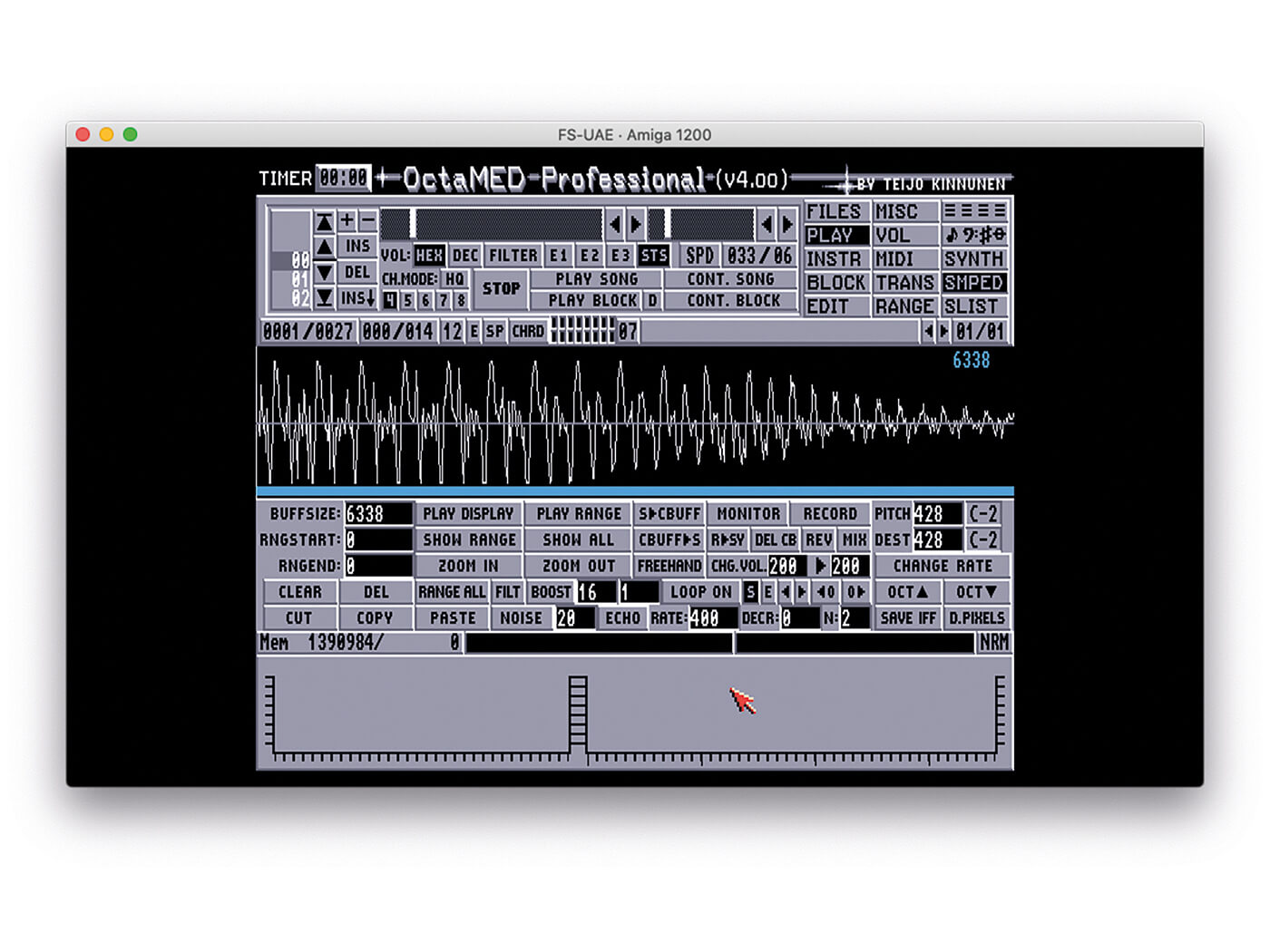

Inevitably, some developers identified the potential of the tracker to be a pure tool for musicians, as well as an instrument for videogame and demoscene programmers. Debuting in 1991 with the ability to send MIDI data via an Amiga MIDI interface, and offering a drag-and-drop stave view, a sophisticated built-in sample editor, and a synth sound generator, OctaMED was a dream come true for cash-strapped aspiring producers. It could even play up to eight tracks simultaneously. However, this reduced the output level of the channels, and the resulting decrease in volume and higher relative noise floor limited its usefulness when it came to making records.

Even with just four tracks, OctaMED was a revelation for musicians excited to explore the musical free-for-all that was the early-1990s rave scene. Many hardcore anthems were made with the software, including DJ Red Alert & Mike Slammer’s In Effect, Omni Trio’s Feel (Feel Good), Foul Play’s Survival and, most famously, Urban Shakedown’s Some Justice. Created on two manually synced Amigas, the sub-bass-heavy proto-d’n’b rave banger Some Justice was signed by legendary pop svengali Pete Waterman for his PWL label. A remix of the track reached number 23 in the UK Top 40 in June 1992.

But it wasn’t just the UK hardcore scene that got in on the Amiga action. Australian speedcore merchants Nasenbluten were prolific and enthusiastic users of ProTracker, and Rotterdam-based gabba crew Neophyte also used ProTracker to make their tracks and to perform on stage.

The burgeoning dance scene was a major influence on the demoscene, and Amiga demos from the early-1990s used MOD files for their soundtracks to spectacular effect. Amiga group LSD’s 30-minute hardcore epic Jesus On E’s, which used a massive 15 MOD files to soundtrack its lengthy running time, is the classic example of rave-led Amiga demos.

Essential to the Amiga’s success as an affordable production computer was the availability of extremely inexpensive sampler cartridge interfaces that allowed users to record samples. Sampler cartridges usually featured stereo RCA inputs and would connect to the computer’s parallel port, allowing users to record sounds from CDs, records, tapes or even VHSs. What’s more, entry-level cartridges were inexpensive at only £40, a fraction of the cost of a hardware sampler at the time.

However, even as early as 1993, the Amiga’s 8-bit sound and limited number of audio tracks became sticking points for producers. It wasn’t the end of the Amiga as a sequencing tool though. OctaMED also worked as a MIDI sequencer, with up to 16 tracks in a pattern, allowing users to trigger hardware samplers rather than use the Amiga’s onboard sound. Upon comparing their sounds, the increased fidelity of OctaMED is immediately apparent. Omni Trio’s Mystic Steppers EP, their first release on legendary d’n’b label Moving Shadow, used the Amiga’s onboard audio, while its follow-up Renegade Snares used the Amiga to trigger an Akai sampler and synths. The difference in production value between the tracks is night and day: the breaks on Renegade Snares are far crisper, and it has a much wider stereo image than its predecessor.

As the 1990s wore on, the Amiga continued to be used by producers such as DJ Zinc, who sequenced the original version of jungle anthem Super Sharp Shooter, and legendary breakbeat master Paradox, who to this day uses Amiga-based tracker software to sequence and play live.

Fast track

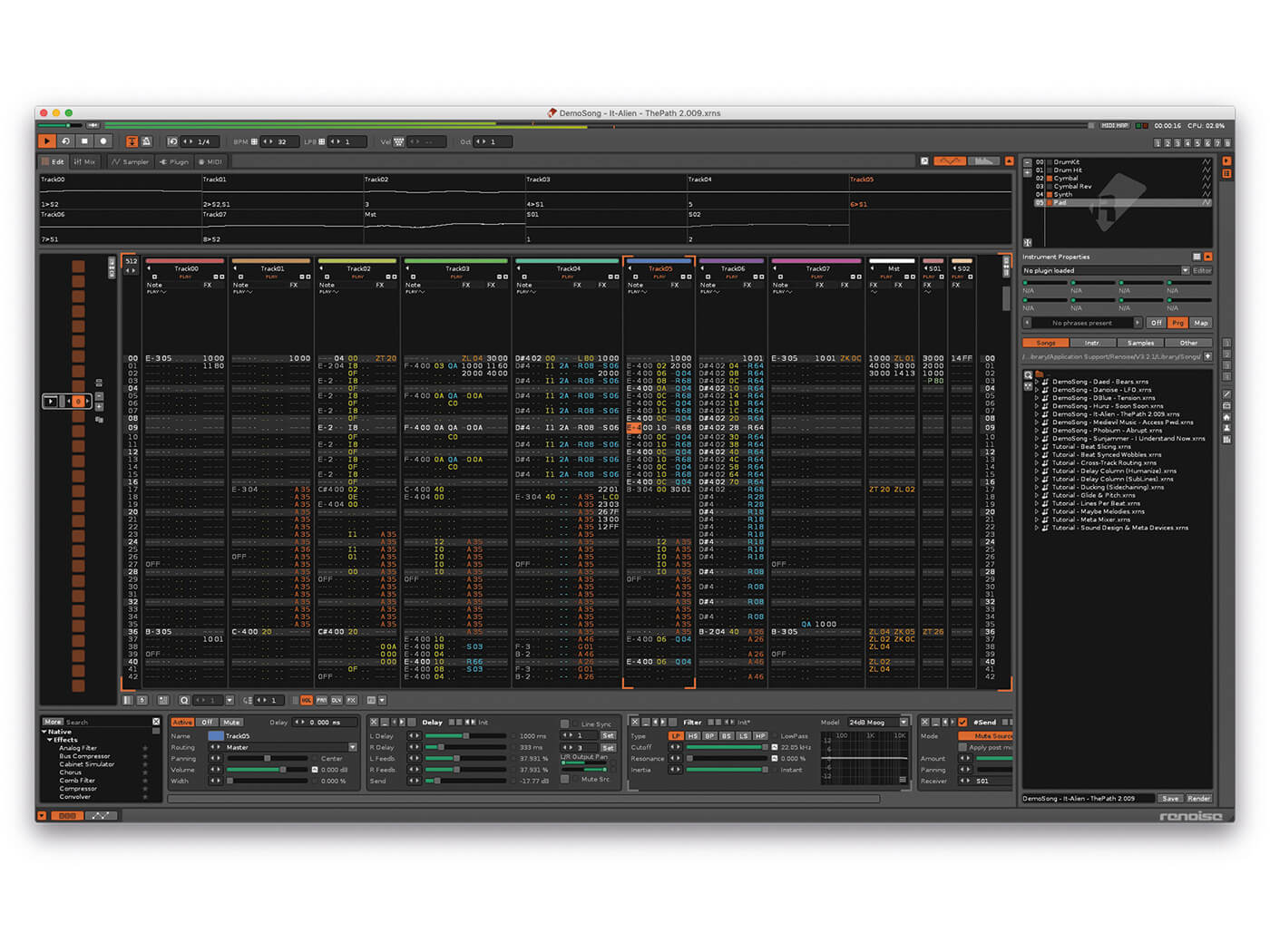

With the demise of the Commodore, tracker development predominantly moved to the PC platform which, thanks to dedicated sound cards, increased audio track counts and 16-bit quality. Fast Tracker II, released in 1994 for MS-DOS, and ModPlug Tracker, released in 1997 for Windows, were two popular traditional trackers for the PC. Between 1997 and 2000, however, Jeskola Buzz took things to another level with its graphical modular audio routing environment. Sadly, Buzz suffered something of a stop-start development because its creator lost the source code. During its absence though, in 2002, Renoise appeared to fill the gap.

Renoise was based on the code of NoiseTrekker, created by the late Juan Antonio Arguelles Rius, AKA discoDSP co-founder and FL Studio developer Arguru, immortalised in the Deadmau5 track of the same name. Renoise brought the tracker up to date with the era’s audio and MIDI-sequencing DAWs such as Cubase SX, adding support for plug-ins and Rewire, plus some esoteric enhancements – among them the ability to use the audio output of a track as a parameter value generator.

Still much in development, Renoise remains the leading commercial tracker software of the day. Those looking for a free alternative, however, should consider OpenMPT, the open-source version of ModPlug Tracker. SunVox, another freeware tracker that offers modular sound generation, is also worth investigating, and is available on an array of platforms, including Mac, Windows, Linux, Android and iOS. Trackers have also made their way to the Nintendo Game Boy thanks to Little Sound Dj, which turns the handheld console into a music workstation, and even to digital calculators, thanks to HoustonTracker 2, which is compatible with various Texas Instruments devices.

The next evolution of the tracker comes in the form of the Polyend’s Tracker and XOR Electronics’ Nerdsynth (the latter is also responsible for tracker-based Eurorack sequencer NerdSEQ). These standalone hardware devices are designed for live performance, and have the potential to take the tracker out of the bedroom and onto the stage. Prepare yourself, then, for the revenge of the nerds.

Look out for our review of Polyend’s Tracker, coming soon.

For more essential guides, click here.