Music For Picture: The Ultimate Guide – Composing Your Score

In part 2 of our ultimate guide to making music for picture we bite into the meat of the subject and look at the process of creating the score, including tutorials on creating an action and suspenseful trailer soundtrack. Be sure to check out part 1. The compositional process It’s time for the compositional process […]

In part 2 of our ultimate guide to making music for picture we bite into the meat of the subject and look at the process of creating the score, including tutorials on creating an action and suspenseful trailer soundtrack. Be sure to check out part 1.

The compositional process

It’s time for the compositional process to begin in earnest. Different composers have various ways of progressing at this stage. Some, for example, might be given what is known as a Temp Track, where the director has provided some suggested music for the piece (a guide audio track with music and sometimes effects). While some composers might think that this is stepping on their delicate, creative shoes, a Temp Track is a great way to get a glimpse of what is going on inside the director’s head. Here’s what Aisling Brouwer (TV composer for shows such as The Apprentice, The Calling and The Taste) has to say on this part of the process…

“More often than not, a Temp Track and/or reference music has been added during the edit,” she says. “Rarely, the composition comes before the edit. If this is the case, or if the track is production/library music, I write the track according to the stylistic brief, but not directly to picture.

Once I’ve established the musical palette, I start by tempo mapping and marking the various hits, builds, fades, transitions and so on. I then get cracking on with the work by establishing the main compositional elements.”

Creating an action-trailer soundtrack

1. Most trailers have to get across the story in a couple of minutes. This usually starts by setting up the plot very quickly over a more atmospheric musical interlude that might use a few elements of the more exciting part that inevitably comes in later. Here, we’re using Blade Runner 2049 as an example, which starts with atmospheric pads.

2. Any action elements early on are dealt with with big percussive slams which again will be reintroduced at quite a pace when the trailer reaches its exciting peak. In this case, there’s an early interlude before the trailer starts its dramatic build. Usually we get the logos of the production companies at this point, as we slowly begin our dynamic journey.

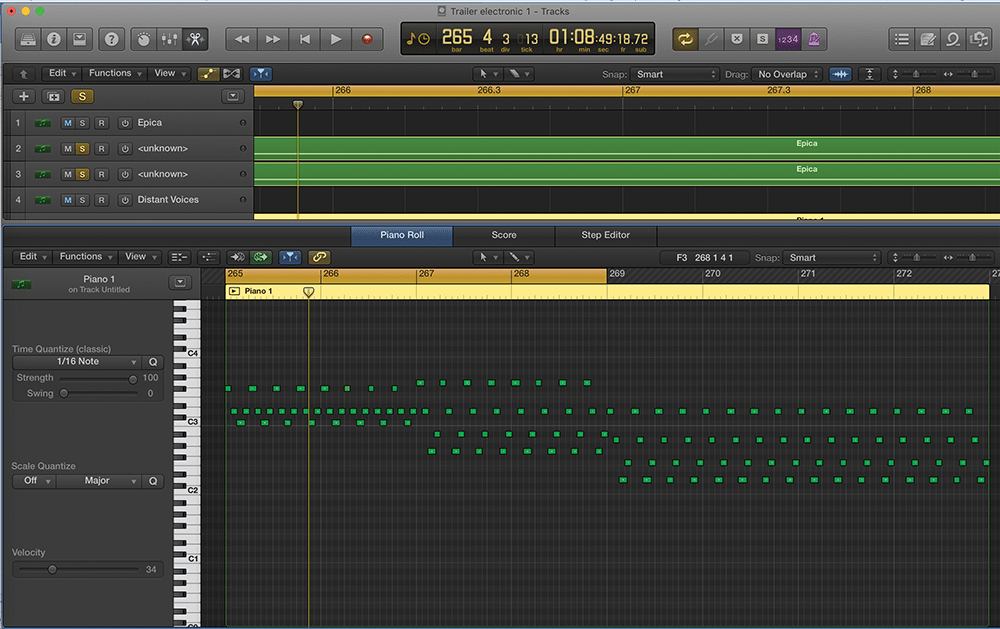

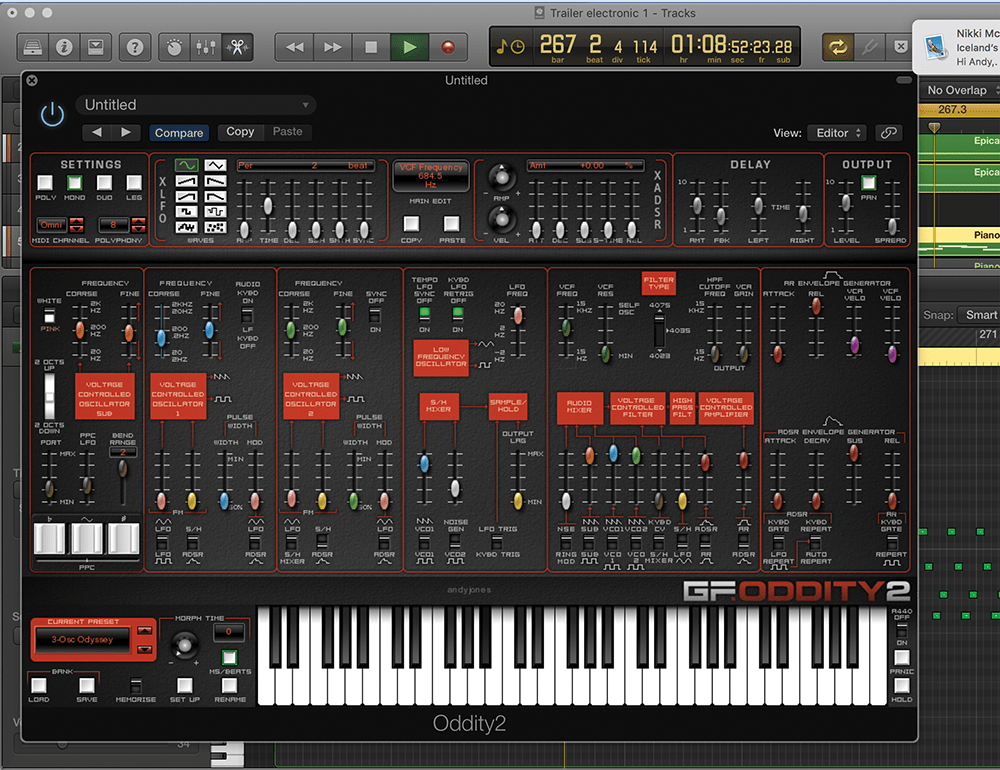

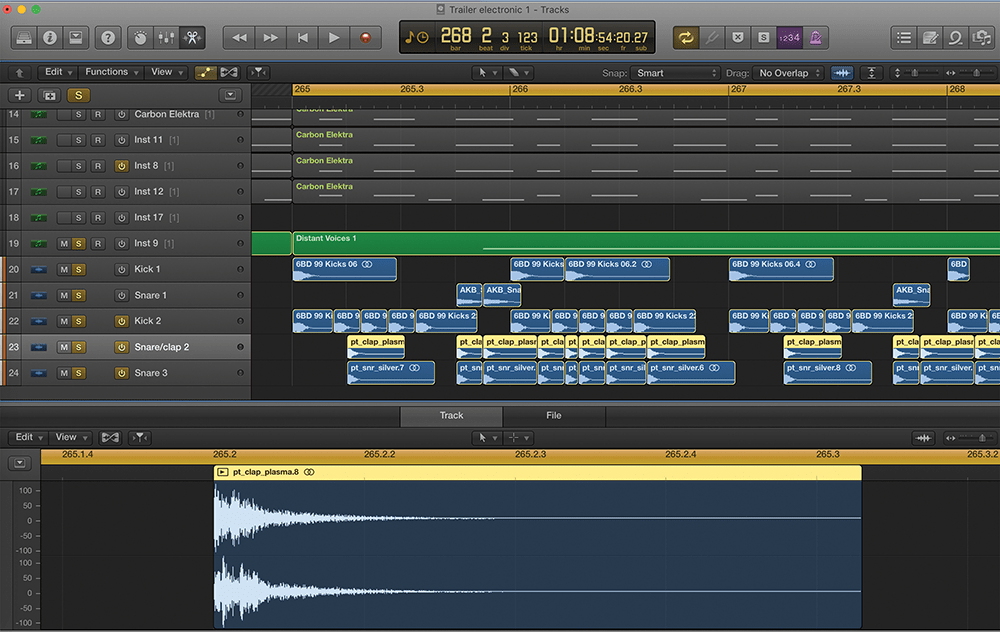

3. This is an out-and-out electronic trailer and the ‘on trend’ electronic musical motif is most definitely the arpeggiator (thanks to Stranger Things). We’ve replaced the one in the trailer with our own software version, complete with chord changes over eight bars, and programmed the actual notes for flexibility in the edit.

4. This is very much the second act of the trailer, setting up more of the plot and there is a lot more dialogue which must shine through – your music shouldn’t clash. As such, we’re keeping the arpeggiator going and only altering its sound with the frequency and resonance dial on the original Oddity synth.

5. In any action trailer, you can guarantee that the third act will have all of the excitement. In this case, as soon as Harrison Ford says: “They know you’re here” and the music drops away, you know it’s time for the real sonic action to start to match the onscreen spectacle. Explosions, quick-fire cutting and pulse-pounding music are dead certs in this section of the trailer.

6. Every action trailer uses big blasts of snare-like machine-gun percussion to match the quick edits on screen. We’ve matched three different snares together for a rhythmic pulse that takes a lot from the original score. It builds and builds towards the trailer conclusion of a sudden drop away of audio with the release date shown on screen. Tickets will now be excitedly booked!

On your marks

Obviously, the compositional style will also vary from project to project and we are in no position to tell you how to compose music for individual projects. But, again, there are some rules that you should try and adhere to when writing music to picture.

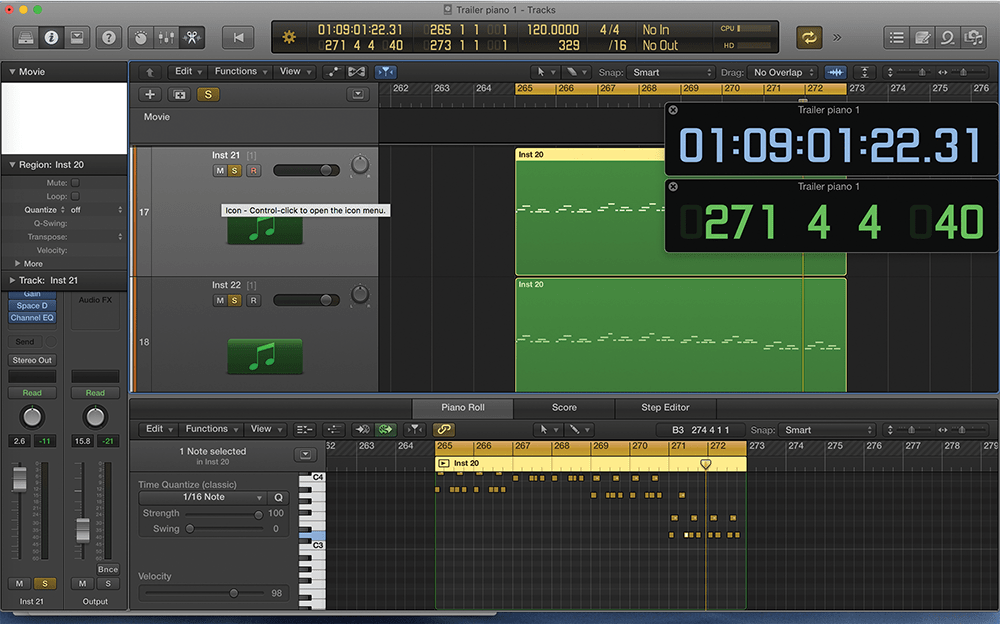

Firstly, use those cue sheets we mentioned above, especially as most DAWs enable you to write unique cues for individual pieces of music or timecodes in a soundtrack. Cues can have all the information about the music, its style, when it comes in and goes out, its tempo (including any changes) and how it fits in with the overall picture.

Use a series of markers here and the SMPTE timecode position of each one (rather than the bars and beats that your DAW offers) because you might find yourself jumping around and the SMPTE give you a better relative and overall position in your soundtrack when tied to the video you’re supplied with. SMPTE (developed by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) is the code used in film and measured in hours, minutes, seconds and frames and adheres to the 24-frames-per-second standard.

If you’re supplied with much of the finished edit, the spotting session with the director should help give you a good overall idea of where the music is going. You should by now have an idea of the type of sound you’re after.

This is probably the key to the whole process and what you are bringing to the project: the BIG soundtrack idea. For example: will it be electronic and futuristic; traditional and orchestral? Will it be incredibly simple or incredibly complex? Is there going to be a repeated melodic theme that comes through, perhaps played with different sounds being played or over different keys? Will each character have a John Williams-esque theme, à la Darth Vader? Is your soundtrack more about the sonic textures than the melody, the sound design rather than a traditional score? All of these should be part of your ‘big idea’ and come at the early stages of composition – or even right after those initial spotting sessions.

You might decide on a trademark sound – Thomas Newman famously used a treated piano when scoring such classics as American Beauty and The Shawshank Redemption. You might find just one riff provides an insistent calling card throughout the film, as with Hans Zimmer in Interstellar, where Philip Glass-like cycling was used to great effect. In Dunkirk, Zimmer used industrial noise to even greater effect, alongside some more traditional scoring – as well as a clever usage of an insistent clock ticking, as though there wasn’t enough drama in that film already!

Creating a suspenseful trailer soundtrack

1. This time, we’re using Arrival as an example template trailer with a more suspenseful twist, rather than complete action. Again, though, this one opens with a scene-setting intro which has very little music, and a fair bit of dialogue to set the trailer up. Often in these types of trailers, we have little aural ‘glimmers’ or perhaps single-note piano that marries up with each reveal.

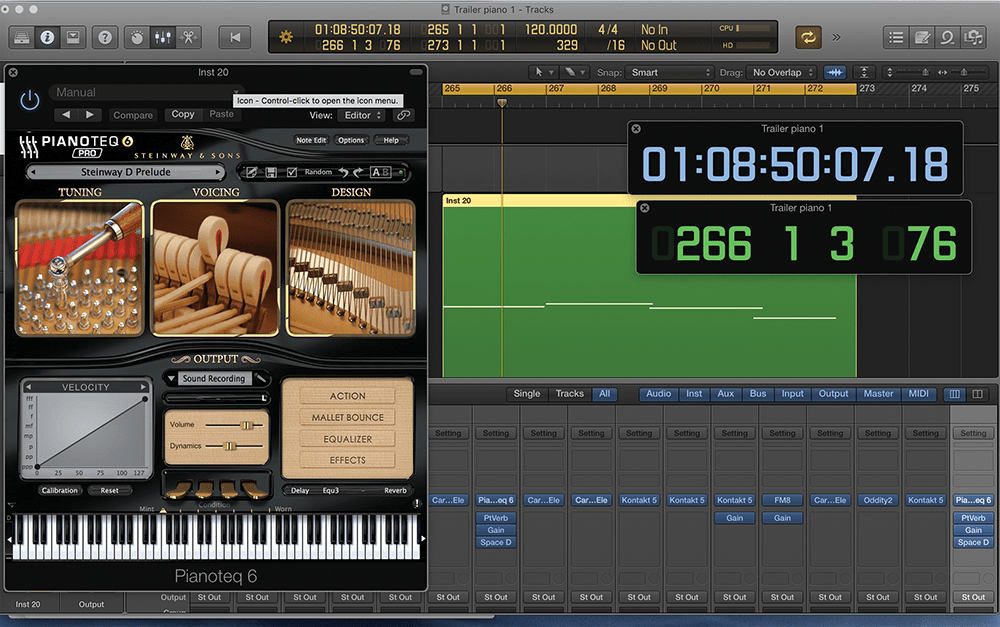

2. We’ve copied the piano theme using a simple chord progression with a fairly sad feel about it to cycle around. We can also add the occasional pad shimmer just to give it some interest. For the piano, we’ve

used the excellent Pianoteq 6, which offers some piano sounds with a great edge to them.

3. The first half of this trailer then sets up the whole plot and the soundtrack is really there to provide suspense. This is where your own sounds come in and you can let loose trying out your own atmospheres and textures. The inevitable ‘mid point’ comes, though, where the film opening time is announced and the tension simply has to start building.

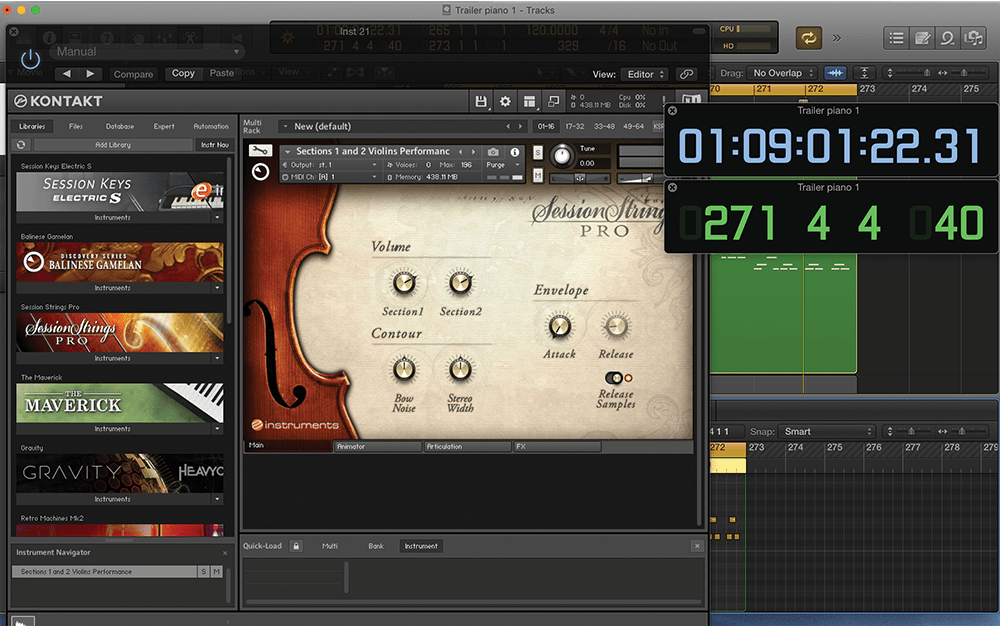

4. In this case, rather than an electronic arpeggiation, we’re in the land of proper orchestration. You don’t have an orchestra? No, but thankfully you may have access to Kontakt or a decent sampler and can provide your own strings that way. We’re using NI’s Session Strings, which can make you sound like you know your way around any string instrument.

5. Programming a simple arpeggiated riff for the strings will give you some tension – but can also sound, frankly, like a piece of technology trying to emulate an orchestra. One trick to use here is to double the string sound but use a slightly different sound to give more exact orchestra layering, which also helps build tension.

6. You guessed it: as plot line after plot line is revealed, so you unleash more tracks of music to build yet more tension and – you know it – you’re going to drop the whole thing away just before the end credits/show times are revealed. This time, though, no fast-paced percussion, just more orchestration (or Kontakt – no, not that kind of contact).

So you want to become a film composer?

Advice part 1 Intern!

There’s no clear and obvious route to becoming a successful media composer. Matthew Margeson has scored blockbusters like Kingsman: The Secret Service and he started off studying film composition at Berklee College Of Music. Yet even having studied at the finest of institutions, Margeson realised that the best ‘route in’ was to intern – and expect to work for free.

“I was helping to maintain the studios and doing software updates,” he says. “When there was a new piece of gear, I’d learn it, hook it up and start figuring out the tech. I was getting a taste of how things worked. It’s also important to form relationships with different clients, producers or directors and maintain those when you’re not working for them. There are lots of people in the world that can write fantastic music, but that’s only a part of getting work.”

Junkie XL agrees. The LA-based Deadpool and Dark Tower composer adds: “It doesn’t need to be a composer you admire – anyone that works and makes music for film and TV is interesting to work for. You have to learn so much about the process and how this works, what the dialogue is with the studio and the director, and what character flaws you may need to work on to become successful in this business.”

If you make it…

Sometimes, directors might need to be told what they want. This month’s interviewee, Junkie XL, has worked with Zimmer on a lot of famous projects as well as scoring Deadpool, Mad Max: Fury Road and many other blockbusters himself. His approach to dealing with directors is unusual and works because of it. As he tells us in his interview: “You have to be open to suggestions, but also come up with a great idea”.

TV composer Sheridan Tongue agrees that being obvious is not always the right way to approach a project. “Directors are always looking for original and inspiring music and I think that mine ticked the box. One of the main reasons that I was asked to score Into The Universe With Stephen Hawking [a major series for the Discovery Channel] was that my showreel was full of tracks that didn’t sound like tracks from a space documentary!”

If you, as the composer, are given the aforementioned Temp Track from the director, then it’s wise to use the best elements of it – the director included it for good reason.

However, some composers aren’t supplied with a Temp Track and use a different approach to the spotting process, preferring to start compositions with early rushes of the film. Sheridan Tongue has a different process again, as he is drip-fed scenes as they appear and then returns to the spotting process mid-session.

“Once shooting has begun, then when I begin to get rough scenes from the edit,” he reveals. “That is the most inspiring point for me, as I can begin to experiment and really get into the essence of the show. The edit process can take between four to six weeks and by the time the picture is locked (the Final Cut), I like to have the style nailed down.”

He says that, at this point, “the editor will be using my music, so everyone can hear the tone and style and provide feedback at some stage. Then I have a meeting with the director, producer and editor and

we watch the cut together, going though every scene and discussing where there will be music, asking, ’What does the music need to do?’

“Then I will usually be given between two and three weeks to compose and record all the music for a 60-minute show. Quite often, I will mock up cues with samples and play them to the director before I record them with musicians. Sometimes, though, I will go ahead and record solo musicians quite early on in the composing process – so my tracks are always developing.”