Music For Picture: The Ultimate Guide – Establishing the Mood

There are more videos being produced right now than ever before… and every single one of them can be improved with decent sound effects and a great soundtrack. MusicTech looks at some of the rules – and non rules – when it comes to creating music for picture, from scoring movies to music videos, and […]

There are more videos being produced right now than ever before… and every single one of them can be improved with decent sound effects and a great soundtrack. MusicTech looks at some of the rules – and non rules – when it comes to creating music for picture, from scoring movies to music videos, and we’ll even score our own trailers along the way…

Whatever your moving images, be they holiday memories on your phone, corporate videos, amateur plays, or even full-blown Hollywood masterpieces, we can guarantee that each and every one will be enhanced with a decent soundtrack. The art of putting an audio track together with visuals has never been so important.

As a music producer in the 21st century, you should, at the very least, be engaged with the idea of getting your music soundtracked to video. If you want an outlet – paid for or otherwise – there are now more TV channels and other content platforms churning out video than ever before, and there are also more library (or ‘sync’) companies. As a working producer, it’s easy to get involved and grab a part of this action, so learning the art of soundtracking – so you can demo your music alongside video – is an absolute must.

This feature is primarily focused on producing scores for films but in reality, of course, there are probably only half-a-dozen composers in the world right now who can, hand on heart, call themselves A-list movie scorers. But don’t let that dishearten you. If we aim for the top, the same fundamental rules and practices can be applied to any music-to- picture project. That applies to producing music for anything including college drama projects, corporate videos, music videos or web adverts.

The same principles apply to all soundtracks. The art of spotting, composing, ordering, and using trial and error – all of these things apply just as well to producing music for a friend’s promo video as they do to a short two-minute, tension-building sting for an international movie trailer.

Over the following pages, we’ll look at the many various ways that top TV, film and documentary composers work with directors when producing a soundtrack. We’ll look at some of the fundamental practices involved in a typical composition, explore some of the tech terms that go with it, detail the numerous pieces of software that can help you produce moving scores – from synthetic to orchestral – and finally even produce two very different pieces of trailer music so you can see how the dynamic of a typical trailer track evolves.

It’s not just deep voices, percussive builds and lots of over- the-top impact (although that does all help). So grab your popcorn, sit back and follow our simple guide to producing the perfect soundtrack…

Create your own spotting session

A spotting session is where you sit down with the film director to discuss the music. At Abbey Road – on our recent visit for a MusicTech cover feature – we visited the ultimate spotting location in the form of the studio’s brand-new cinema room: the Mix Stage.

This state-of-the-art room is for dubbing the film score music usually recorded in Abbey Road Studio One direct to picture. It features a 44-speaker Dolby Atmos system (as commonly used in cinemas today) alongside a mini-cinema, complete with cinema-style seats. Like we say, it’s the ultimate place to discuss movies and music together – you really can imagine J.J. Abrams or Rian Johnson sitting here with John Williams discussing musical cues and themes to one of their new Star Wars movies…

Tech terms

Cue

Using the SMPTE timecode, the cue is the position in a film for speech and music (and sound effects) and these positions are usually identified in detail in the spotting sessions.

Delivery format

Talking of delivery, you will be expected to deliver at at least 48kHz, 24-bit resolution, which shouldn’t be a problem with most DAWs. When delivering renders of your soundtrack alongside the video as an example for the director to check, don’t be afraid to compress both – all they want to see and hear are the two together at this stage. In this case, you can get away with compressing using AAC at 256kbps.

Dub

This is the final audio mix for the film and includes everything – speech, music and sound effects. As the composer, you will probably only be involved in the music, so won’t be responsible for delivering the final dub. However, your audio might be expected in…

Stems

Stems are audio tracks from your project, that is instrument and MIDI tracks rendered to stereo audio. By delivering in stems, you’re enabling a certain amount of further mixing to be done after your delivery.

Temp Track

A usually temporary soundtrack, perhaps placed by the director on the film to give an indication of the style or mood of the music required at this location.

Spotting

The process undertaken by the film director and composer to identify the parts of the film where music will go and usually identified using the film position or timecode.

SMPTE Timecode

SMPTE (developed by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) is the code used in film and measured in hours, minutes, seconds and frames. It adheres to the 24-frames-per-second standard of filmmaking.

Theme park

While we don’t expect you to create your own 44-speaker room for your spotting sessions, you should always prioritise sitting down with the creator/director of the visual piece you’re scoring to discuss the project; what that director has in mind about the music: what sonic themes they’d like to hear; which scenes they want music in (and, conversely, which scenes should have no music at all).

This is the time to go through the rough cuts of the film and get an overall idea of the creative intent of the project – the mood and the tone, both visually and sonically. Are there any subtexts that you should know about? And, of course, what is that all-important deadline? It’s time for your own ideas to begin and hopefully marry with the director’s, so create your own spotting session upfront and use it as the foundation to build the sound alongside the visuals going forward.

Sheridan Tongue is best known for providing the TV music for major shows like Silent Witness, Spooks and Wonders Of The Solar System. He says of the spotting process: “I like to speak to the director to establish a rough idea of the vision. What is the essence of this show? What would they like the music to achieve? How much music is there? With orchestra or all electronic? I’m trying to build up a picture in my head on the best way to approach it.”

Beneath the surface

Spotting processes can vary from project to project, as can the relative completeness of the film you’ll start with. You might just be looking at the initial storyboards, very early rushes or even a rough final cut. The downside is that (in the professional world at least) the more finished the film, the less time you will have to come up with a piece of music for it; but at least the director’s vision is all there on film, so you have a complete piece to work with.

Though you should be speaking often, try and get this initial meet done in one detailed, ‘in the room’ session, over a day if possible. Although technology allows greater long-distance communication, we’d say face-to-face meetings are always the best. Use this time to really get behind the themes and narrative of the piece, get a route map of the plot and the characters and their respective arcs. The best possible spotting session takes place when you have the film playing in your DAW and can take notes as it plays through within your composing environment. Now it’s time for the real work to begin…

Setting Up

Whatever your DAW, there are some very good ground rules for working within a sequencer for producing music with visuals. You should always have a template set up, whatever your DAW, dedicated to music to picture. You could have a bespoke video track, set up at the very top of the arrangement, perhaps one that outputs to a separate monitor for ease of watching.

Have special effect and Foley libraries on hand, and also have all channels set up with EQ and compression. In some DAWs, notably Logic, you can also have your timings in SMPTE or bars and beats set out as a separate window for ease of viewing (in Logic, you can choose a ‘giant’ version) and this is also good to have going to the second monitor.

In Live, video is treated very much just like any other audio file. You open it in the Arrange window and can do some basic edits to it, including cropping, cutting and pasting. Cubase is similar to Logic, but you’ll need to make sure that you’ve set up a specific video track before importing the video.

The movie will generally sync to your current DAW project and in Logic and Cubase opens up as a separate QT window that will play your project when you hit play within the window and sync to it (with a thumbnail version running along within the video track itself). In Logic, you can also have it minimised to the top left of the Arrange window, with a special preview option of the video itself along the video track.

1. In Logic you can have your movie shown in a separate QuickTime window or as thumbnails as part of the arrangements. Also useful is the ability to pull out the SMPTE timecode as giant numbers – to look more pro!

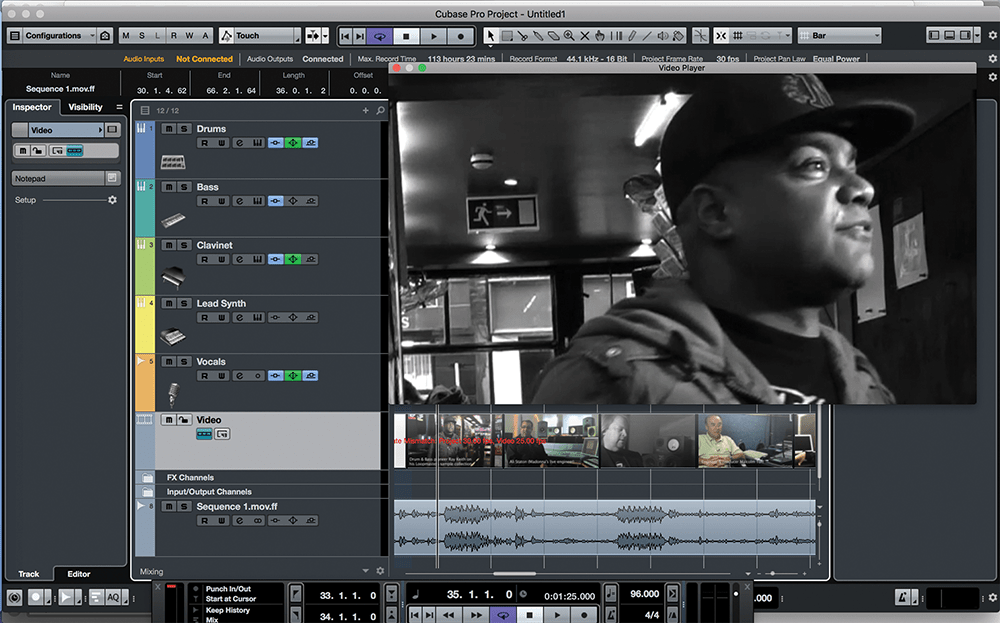

2. Cubase is similar to Logic in that you can see your movie as a QuickTime box or as thumbnails within the Movie track. However you will have to set this up as a movie track to start with (which is very easy, under the Create option).

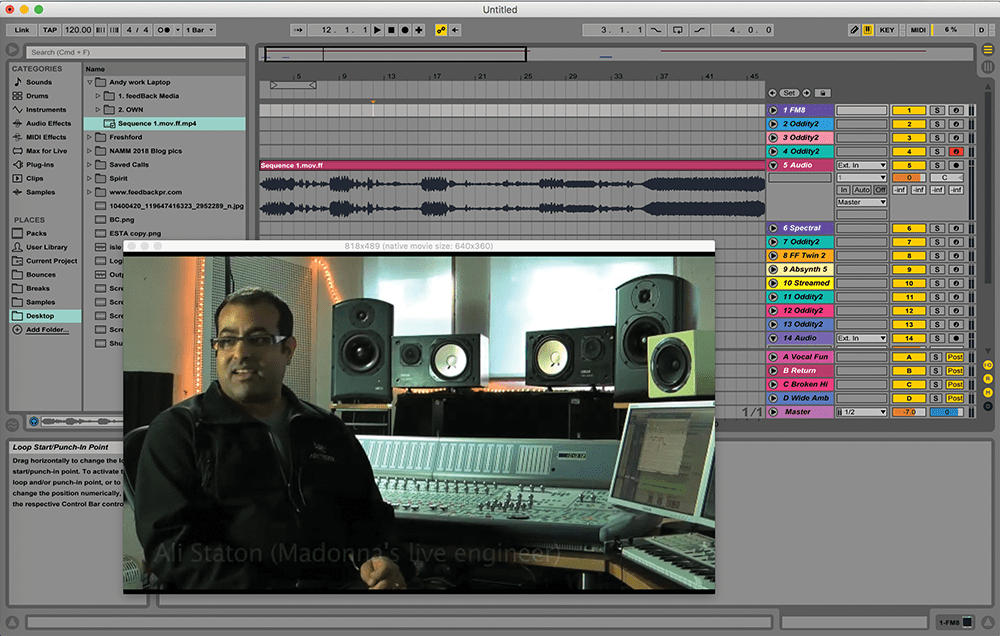

3. In Live, a movie file is treated very much like a regular audio file and one that you can edit with basic controls as you can in most DAWs. But really, you want to use a proper video editor for editing, or leave that part up to the director.

Settle the score

Most DAWs now have features for composing directly to picture and allow you to easily extract an existing soundtrack from a video and replace it, or simply have it running as a separate audio track to the video. This is recommended after your first spotting session with the director, as now you take the video into your DAW and make some manual spots as it plays through (as we said earlier, this is ideally done with the director initially).

With Logic, for example, you simply open up a QuickTime movie and the software can detect all major edits and you can make notes as it progresses within what you might call your own virtual Master Cue Sheet. These notes can be on ideas, tempos, atmosphere, mood, whatever ideas that you have each time you watch the film. Now you’re ready to make music…