Online Collaboration – The Ultimate Guide

There are now more ways than ever to collaborate with other musicians and produce great music without ever being in the same room. Hollin Jones gives you the lowdown… Technology has changed almost every aspect of music production in ways that not so long ago could only have been dreamed about. You can emulate the […]

There are now more ways than ever to collaborate with other musicians and produce great music without ever being in the same room. Hollin Jones gives you the lowdown…

Technology has changed almost every aspect of music production in ways that not so long ago could only have been dreamed about. You can emulate the outboard used at Abbey Road in a plug-in, track a live band into your iPad, or chop and mash a drum loop into something alien and futuristic. An even greater advance has been the rise of the internet, and it has brought dramatic new possibilities and challenges for musicians.

Most people know that you can host, showcase and sell your music online, but perhaps fewer realise that the holy grail of full online collaboration is now closer to being a reality than at any point in the past.

It’s been possible to communicate online for some time, of course, but the requirements of music recording and production are far more rigorous than sending email or even video calling. We’re still not fully there, or at least we don’t yet have a solution that’s as good as being in a room with other musicians, but there are now many ways in which you can work on music with people in other cities or countries and sacrifice little, if any, quality.

Those who remember the Rocket Network from the 1990s, one of the first serious online collaboration tools, will also remember the dialup internet speeds we had back then and which seem prehistoric by today’s standards. And although we now all have far faster connections, the demands of latency-free audio streaming over the net are still a real limiting factor, albeit one that some developers have worked around in ingenious ways.

The most basic way of collaborating online is also the oldest, and that is to collect all your project data into a folder and upload it to a hosting service and send your music partner the link. If it’s a MIDI-only file you can even email it.

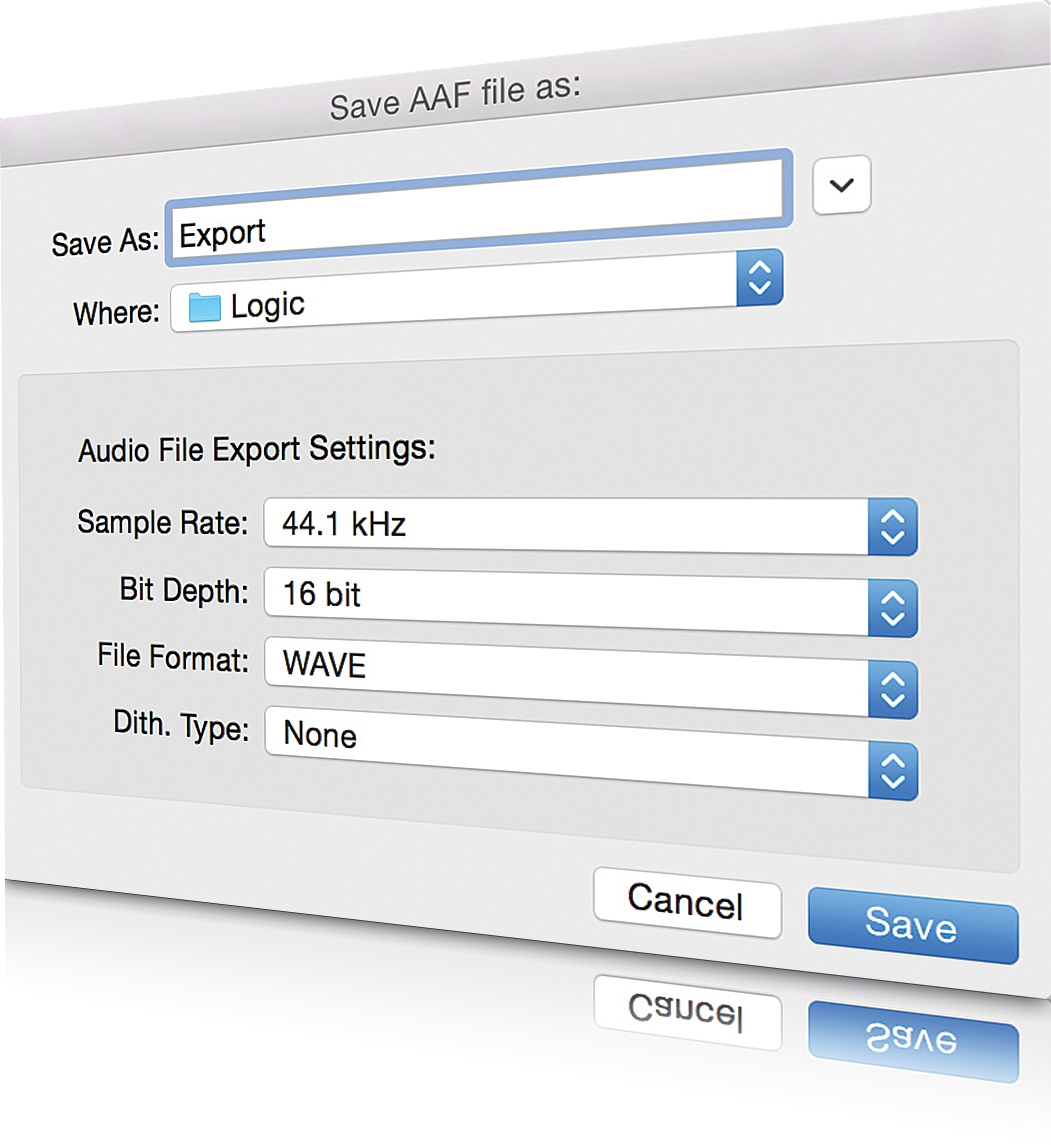

AAF files are a very common file format for online collaboration

The vast amount of storage space you get for free these days means swapping even big projects is easy. But this isn’t particularly ‘realtime’: for that you’ll need a dedicated system such as Steinberg’s VST Connect. A third category of tools is websites that let you compose and even record and use effects, all within a web browser – something that has become possible thanks to advanced web technology.

With so many people having home studios of one kind or another, working together on a musical project no longer means having to be in the same location. If you choose the method that will work best for you and do some preparation and groundwork, it’s quite possible to work effectively with anybody in the world who has a decent internet connection.

Although meeting up is always good, it’s not always possible due to the distances and costs involved or the commitments of the musicians. We’re going to show you the many ways in which you can expand your musical horizons by breaking down the walls of your studio – metaphorically speaking – and opening up the whole world to collaboration.

Making Music Online: The Basics

There are some important things to understand before you get started…

The good news about working online is that, on the whole, digital formats these days are pretty advanced. No serious DAW will make a fuss about the difference between an AIFF and a WAV, or refuse to recognise a standard MIDI file.

But there’s still a lot that can end up being fiddly if you don’t do the groundwork. You’re going to need access to a computer or tablet and have a decent internet connection, which means anything that’s technically broadband.

The faster your downstream and upstream connections, the better. And ideally you won’t have any kind of data cap either as this can scupper your work if it kicks in. A CD quality WAV stream can have a data rate of anything up to 3Mbps and that’s before you factor in all the sources of latency and fluctuations in network strength, as we will see.

If you’re planning on collaborating in the most traditional way, you’ll be sending a folder of material over the web to another user, probably via a file hosting site. It’s important to get a few things clear at the outset. The first is what DAW they’re using. If it’s the same as yours, is it the same version? And do they have the same set of plug-ins? Probably not. If it’s a different DAW, does it have any special requirements? Your first task is to set up the project using pre-determined settings.

You’ll make your life easier if you get your project settings started before you begin

That might mean starting a project at 48KHz, 24-bit WAV and 115bpm, for example. All these things can be set differently of course, maybe 44.1KHz and 16-bit, but if you standardise it before you start and tell your partner, they should be able to open your data without any conversion. It’s possible to convert sample and bit-rates and even tempo but it’s all extra work.

Clean and Tidy

Many DAWs now encourage you to save everything into a project folder but if you haven’t done, you may find an option to consolidate or back up a project in your File menu, which should create a copy of all the relevant files. Software tends to use hard links to audio files so it likes to know the precise file path to the sounds you’ve recorded. If you have a main project folder and everything related to the project is stored within it, that makes everything much easier.

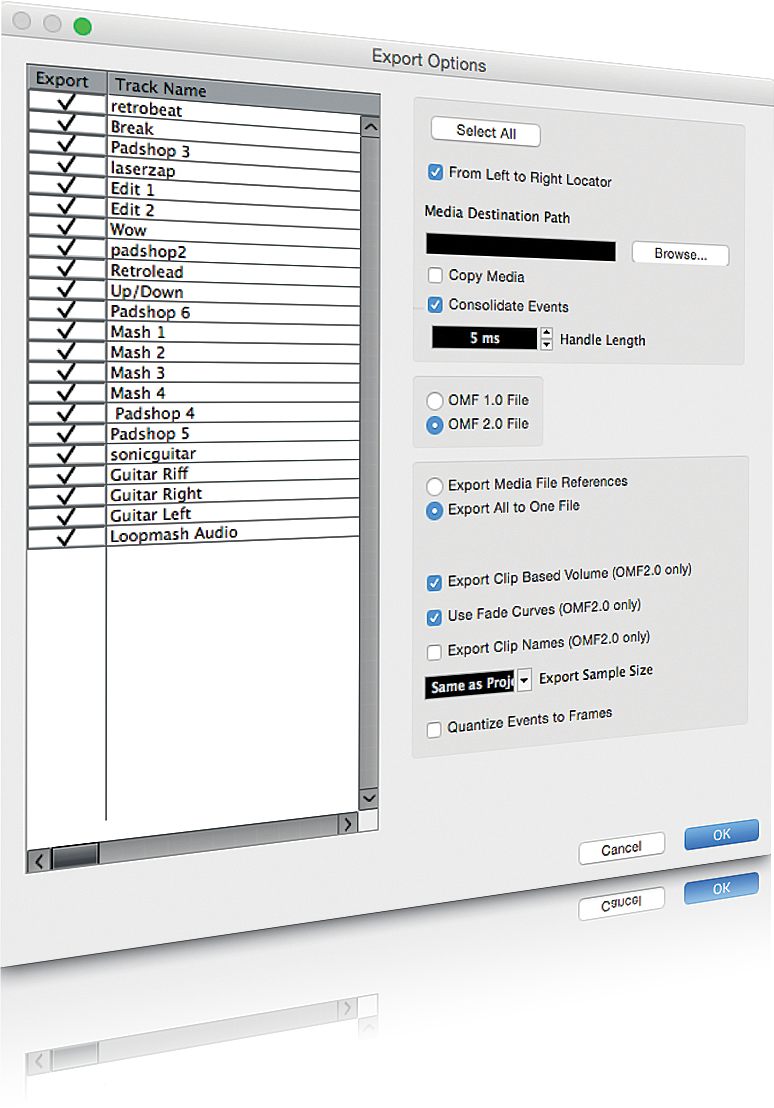

OMF files are a little more basic than AAF but are supported by the widest range of audio and video software at the moment

There is, of course, the issue of plug-in instruments and effects and it’s likely that the other person isn’t going to have exactly the same sound set as you. One option is to let them re-link the MIDI track to a new instrument at the other end or substitute their own effect, but a better solution is to render down virtual tracks before sending.

By bouncing down a Kontakt track for example, or a guitar part with your plug-ins on it, you can make the virtual processing ‘real’ . Of course you can also include the dry version or the MIDI-only track to give them extra options for editing and processing.

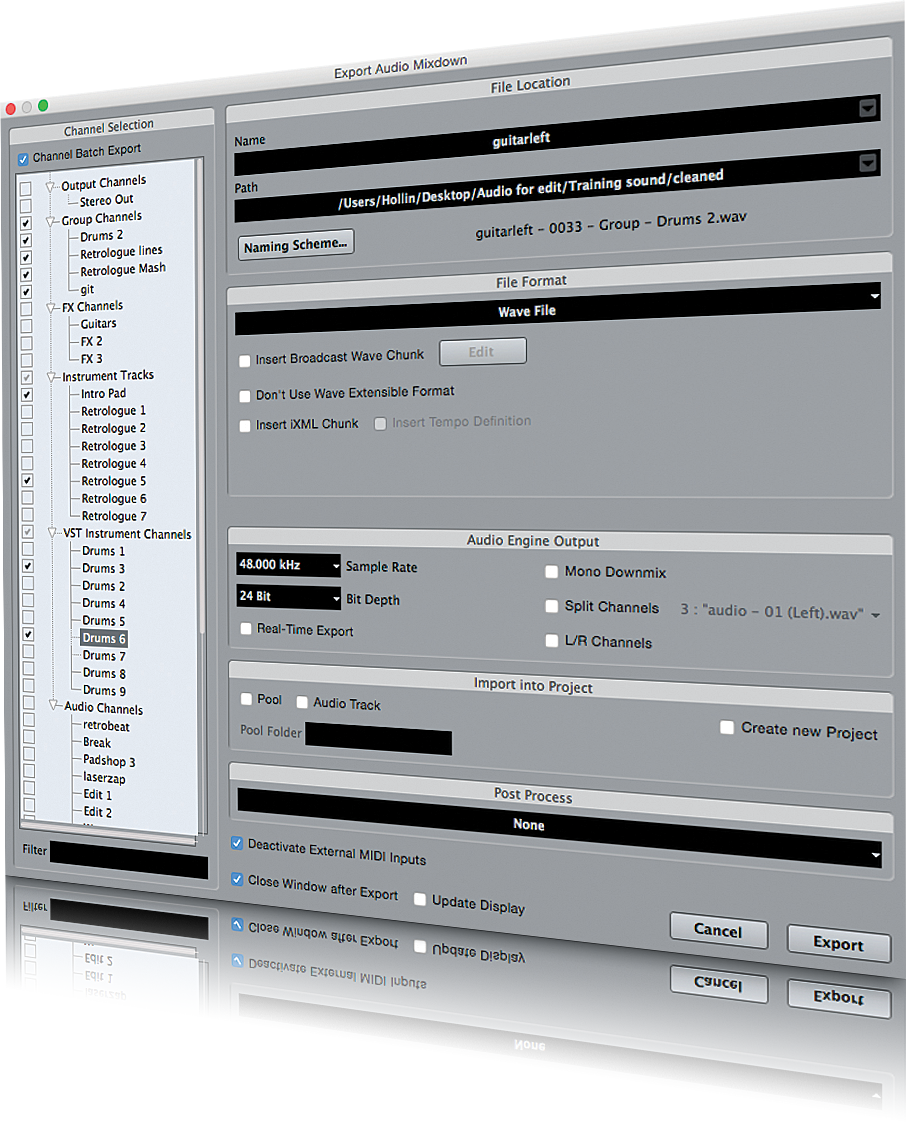

If you’re both working on very different kinds of systems you may want to bounce all your tracks out as you would when exporting stems for mixing, perhaps including dry and wet versions and being sure to set left and right locators precisely to make life easier at the other end.

There are specialised file formats that are designed to facilitate the exchange of raw project data between different platforms for just this kind of task. OMF (Open Media Framework) files were developed by Avid (owners of Pro Tools) as a way of moving between video and audio editing systems without constantly rendering and re-importing media. The format proved useful for DAWs as well, where the requirements are not dissimilar events on a timeline, with some real-time effects.

Open Formats

The OMF 1.0 format could cope with audio clip position, project tempo and some other basic concepts, and OMF 2.0 added volume settings and fades for events as well as clip names. OMF doesn’t support MIDI files (though these can be exported separately) or plug-ins, because DAWs work so differently. As such, OMF is fine for exchanging audio-based projects but certainly has its limits.

Most ‘full’ DAWs support OMF export and import, though things such as advanced mixer settings, scores, surround and so forth are well beyond the scope of these kinds of file formats. OMF has been succeeded by the AAF format which is more advanced and can include more information but this is currently not as widely supported, though Logic Pro X and Pro Tools among others do support it.

There’s also the Mxf format for audio and video interchange, though this hasn’t made much headway in the audio world yet. Different software supports different formats, so it’s certainly worth investigating this as it will save you a lot of messing about later.

The most basic way to swap files is to export stems or to zip and upload a project folder.

Good Housekeeping

The problem with exchanging raw project files between different DAWs is that they all work in very different ways and there’s little incentive for developers to make it easy to switch to a competing product. But you just have to understand the makeup of a DAW project to work around this.

Keep your audio files together, note down the project settings and render down any MIDI and plug-in effect tracks to audio. If you have used external samples, ReFills or sample-based instruments you’ll also need to either make sure these are bundled into the package you send, or render them down as audio too. The difference is that with a rendered file the other person will have less freedom to edit.

Then all you have to do is make sure everything is in place and transfer the project folder to a hosting website like Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive, WeTransfer or something similar. It’s a very good idea to zip the folder before you send it. Not only may this reduce the file size a little but it will also greatly lessen the chance of any files getting corrupted during the upload process.

Project Planning

If you’re collaborating on music with someone who doesn’t live nearby, the techniques for doing it online that we discuss here all have their pros and cons. Some are cheap, and some are expensive. Some tie you to a particular platform while others don’t. And some are simple, and others are complicated. There are parts of the music process that are easier to do online than others, so if you have any scope for being in the same room at any point you should plan to do the hard stuff then, and the easier stuff remotely.

Things that are much easier to do when you’re in the same place include tracking drums, recording multiple players at once as well as recording large instruments such as pianos, or developing musical ideas using a back and forth approach.

Things which are much easier to do over the web include tracking any kind of single-source sounds such as vocals, guitars or horns (assuming you sort the latency out), voice over, listening to and discussing arrangements or mixes, and playing about with and selecting sounds.

Since your time is far less precious when you’re sitting by a computer than when you’ve travelled to see someone, try to separate out the things you have to do into more and less urgent piles. If you do happen to have plumped for a pro solution like VST Connect Pro you have more scope to achieve some of the ‘harder’ things remotely.