The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper at 50 – The Gear Behind A Classic

It’s been five decades since the most iconic album in history was released by the biggest band in the world. John Pickford celebrates the anniversary with a look back at the album’s recording and the gear used… On Thursday 1 June 1967, the world’s biggest-ever band released an album often hailed as their masterpiece, Sgt. […]

It’s been five decades since the most iconic album in history was released by the biggest band in the world. John Pickford celebrates the anniversary with a look back at the album’s recording and the gear used…

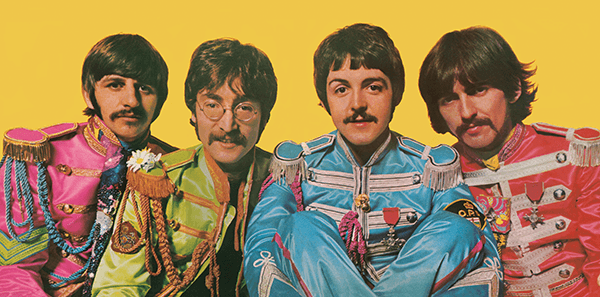

On Thursday 1 June 1967, the world’s biggest-ever band released an album often hailed as their masterpiece, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Beatles’ eighth album is surely the most iconic album in the history of rock music, from its eye-catching Peter Blake-designed cover to the very last piece of audio printed into the run-out groove.

Produced with the same four-track technology the group had been using for three years, Sgt. Pepper… represents the pinnacle of what could be achieved in a recording studio in 1967. Over the next few pages, we’ll examine the creative processes and technological innovations that went into producing ‘The Greatest Album Of All Time’.

When The Beatles arrived at EMI Studios on 24 November 1966, they entered a new phase of their career. Their tours of the Far East and North America the previous summer had been fraught with disaster, particularly in the aftermath of John Lennon’s remark that the group were now “more popular than Jesus”, leading to the public burning of Beatles records and memorabilia. Weary of the rigours of touring, the group finished their final show on 29 August 1966, at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, and vowed never to tour again.

“Now a full-time studio band, The Beatles were free to spend as much time as they wanted creating an album to surpass all others”

Now a full-time studio band, no longer under the complete control of producer George Martin, they were free to spend as much time as they wanted creating an album to surpass all others in terms of scope and ambition. The group had begun experimenting with unusual sounds on 1965’s Rubber Soul album, expanding their standard two guitars, bass and drums line-up with sitar on Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown).

The following year’s Revolver continued the search for new, exotic sounds, culminating with the psychedelic Tomorrow Never Knows, which pioneered the use of tape loops. Revolver also featured the talents of Geoff Emerick, a newly promoted young recording engineer who relished the search for innovative techniques to create pioneering recordings and was more in tune with the group’s demands than their former engineer, Norman Smith.

REDD.51 Mixing Console

Most of the sessions for Sgt. Pepper… were conducted in EMI Studio Two on the REDD.51 console, which had replaced the REDD.37 – still employed in Studio One – in 1964. In essence, the REDD.37 and .51 designs were similar; the latter model was a sleeker design, making use REDD.47 amplifiers instead of the earlier model’s Siemens V72S units.

Both mixers featured 14 Painton quadrant faders, which controlled the signal level of eight microphone input channels, two auxiliary channels and the four centrally placed faders controlling the outputs to the Studer J37 four-track recorder.

The REDD.51 featured two types of equaliser – ‘Pop’ and ‘Classic’ – both of which provided 10dB of shelving boost or cut at 100Hz. The ‘Pop’ equaliser, as used on The Beatles’ sessions, behaved as a peak-boost EQ centred around 5kHz, and a shelving-cut EQ at 10kHz.

Other controls found on the console included dedicated echo sends and returns with comprehensive monitoring facilities, and various styles of pan-pot, including a unique ‘Spreader’, which controlled the width of the stereo image. Sgt. Pepper… derives much of its sonic quality from the pure valve sound of the REDD.51, arguably the best-sounding console that EMI built.

Making history

The first song recorded for the as-yet-untitled new album was Lennon’s wonderfully surreal Strawberry Fields Forever. However, it never made the final cut, instead released as a double A-side single, along with Paul McCartney’s Penny Lane, also lifted from the album’s early sessions.

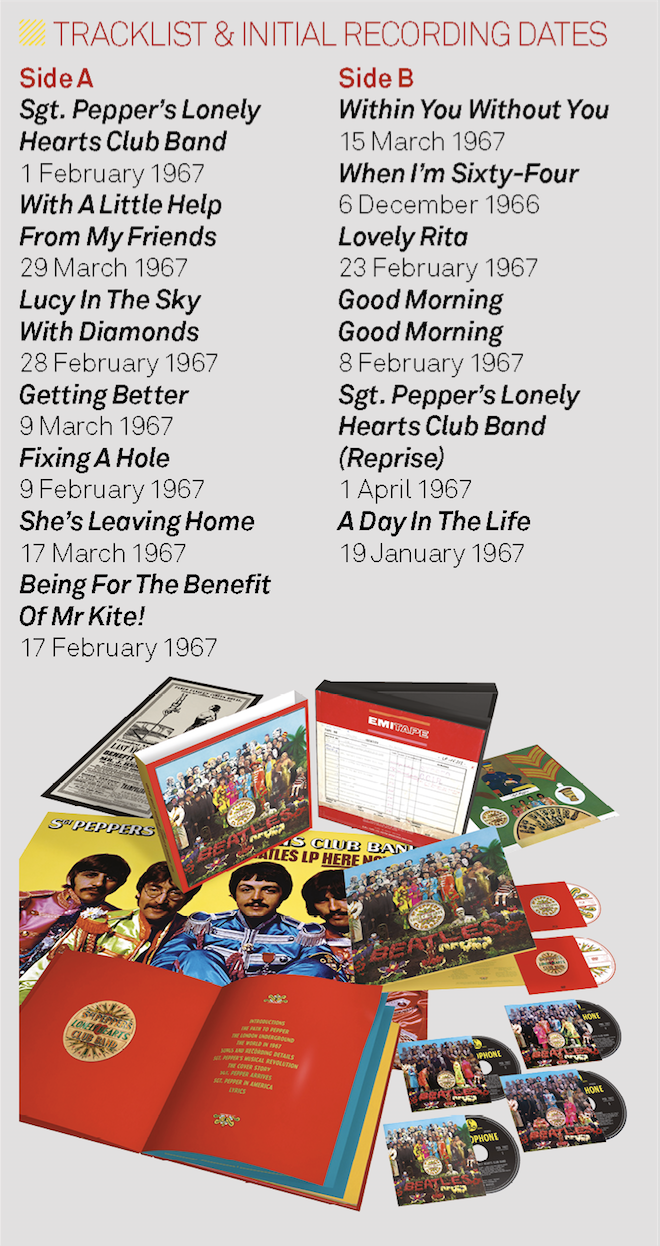

In between these two masterful recordings, The Beatles taped McCartney’s music-hall inspired When I’m Sixty Four, however, the ante was upped once again on 19 January 1967, with the initial recording of Lennon and McCartney’s magnificent A Day In The Life.

Lennon’s portion of the song was partly inspired by his autumn 1966 experience of filming How I Won The War with Beatles’ film director Richard Lester, while other lyrics referred to news in the Daily Mail on 17 January, reporting the death of the group’s friend and heir to the Guinness fortune, Tara Browne, who had crashed his sports car into a stationary lorry. The same edition of the newspaper carried a story about there being 4,000 potholes in the roads of Blackburn, Lancashire.

A Day (and several weeks) In The Life

Initial takes of A Day In The Life were recorded on two of the four available tracks on EMI’s Studer J37 tape recorder. Onto Track 1 went a backing consisting of John playing acoustic guitar mic’d with a Neumann KM54; Paul on a Steinway grand piano mic’d with a Neumann U67; George Harrison on maracas (Neumann U47) and Ringo Starr on bongos (AKG D19c). Recorded simultaneously onto Track 4 was John Lennon’s vocal, mic’d with a Neumann U47, compressed with a Fairchild 660 and treated with a healthy dose of repeat tape echo.

Engineer Geoff Emerick explains: “We’d send a feed from John’s vocal mic into a mono tape machine and then tape the output. There was a big pot on the front of the machines and we used to turn up the record level until it started to slightly feedback on itself and gave this sort of twittery vocal sound.” The echo was recorded live with Lennon’s vocal as he was singing and, hearing it in his cans, he was able to use it to inspire his phrasing.

At this stage, the group was unsure how to join John’s verses with Paul’s middle section, so they left a 23-bar gap which, at this stage, featured Beatles’ roadie Mal Evans counting out the empty bars with increasing amounts of tape echo, ending with the ringing of an alarm clock, which perfectly fitted Paul’s opening line: “Woke up, fell out of bed…”

After the addition of more group overdubs the following day, including Paul’s bass and Ringo’s drums, and the recording of Paul’s lead vocal contribution on 3 February, the track was put on ice for a week. During this period, the Beatles worked on three new songs for the album, including what was now going to be the title track, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, begun on 1 February.

Nine takes were attempted, featuring Paul and George on electric guitars and Ringo on drums with lots of reverb, all recorded onto Track 1. Paul then overdubbed his bass part onto Track 2 of Take 9. The bass was recorded using DI for the first time on a Beatles session, and the idea intrigued the technically unaware John Lennon so much that he asked George Martin if he could DI his vocal.

The producer replied, “Yes, if you go and have an operation. It means sticking a jackplug in your neck!”

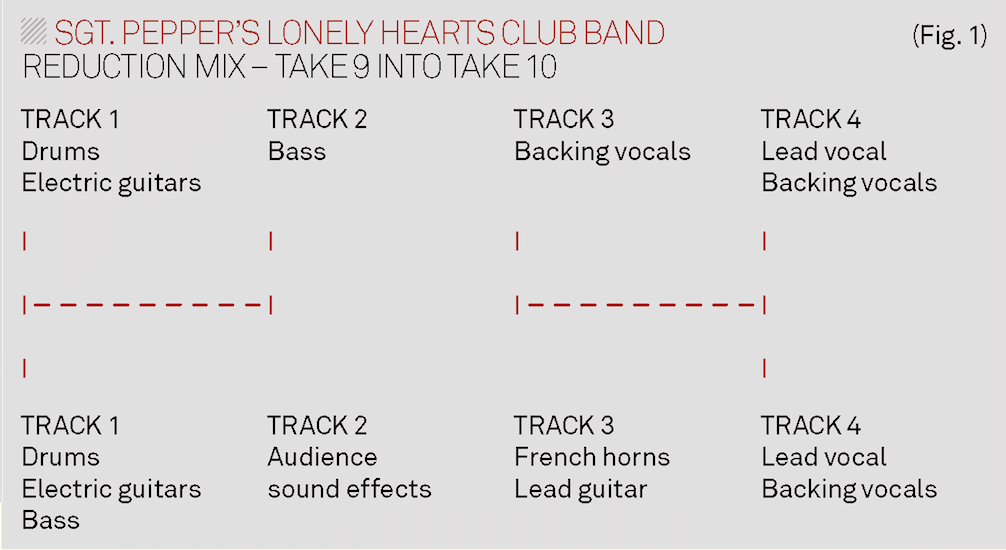

The vocals, recorded conventionally with Neumann microphones, filled the remaining Tracks 3 and 4 and then a reduction mix (Take 10) was made by bouncing a mix of Tracks 1 and 2 onto Track 1 of a second J37, with the vocals bounced to Track 4 (see fig. 1).

Several weeks later, work resumed on the song with the addition of French horns onto Track 3, after which Paul overdubbed a stinging lead guitar part in the gaps where there were no French horns. The final overdub came courtesy of EMI’s sound effects library, with the sound of audience noises onto Track 2.

Studer J37 Four-track Recorder

EMI bought four of the Swiss-made J37s in 1965, costing a staggering £8,000 each. The machine was a vast improvement on the Telefunken machines they replaced. During Pepper…’s sessions, two J37s were placed in the control room, rather than EMI’s remote tape rooms, for better communication.

The J37’s superb sound quality enabled several reduction mixes in the course of each song’s creation. Once all four tracks were filled, they could be mixed and bounced onto one or two tracks of a second machine and the process would give the group extra tracks for more overdubs.

If the song required still more work, the process would be repeated. As an example, Getting Better received three reduction mixes to accommodate the many overdubs the song required.

To facilitate the ambitious orchestral overdubs featured on A Day In The Life, technical engineer Ken Townsend devised an ingenious method of syncing two J37s by recording a 50Hz tone, acting as a substitute for mains current, onto a vacant track of the first machine to drive the motor of the second.

Picking up steam

The second week of February saw two new songs introduced to the sessions: John Lennon’s Good Morning Good Morning and Paul McCartney’s Fixing A Hole. Lennon’s song, inspired by a television commercial for Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, featured a brass section; however, true to the group’s desire for unusual sounds, the brass track was heavily limited through a Fairchild 660 and, on the mono version only, flanged.

More library sound effects were used – this time, the sound of various animals, concluding with the clucking of a hen that segued seamlessly into the opening guitar note of the following song, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (Reprise).

For the recording of Fixing A Hole, the group decamped to another studio, Regent Sound in Tottenham Court Road. Like EMI, Regent Sound used J37 recorders. However, their mixing console was a solid-state 12×4 Tiros Electronics model.

This was the first of several occasions when The Beatles would record outside of EMI’s studios while signed to the company, although the only time during the Sgt. Pepper… sessions. The recording made use of Regent Sound’s harpsichord, played by George Martin while the group performed on their regular instruments.

“Several members of the 40-piece orchestra wore novelty items: clown’s noses, fake bald heads, and plastic stick-on nipples”

The following day, 10 February, the group returned to Abbey Road for the most memorable of all Sgt. Pepper… sessions – the orchestral overdub for A Day In The Life. The session was filmed and shows the group in their trendy psychedelic clothes along with the 40-piece orchestra, several members of which wore novelty items such as clown’s red noses, fake bald heads and plastic stick-on nipples, while Erich Gruenberg – leader of the violins – wore a gorilla’s paw on his bow hand. Various friends and associates of the group, including members of The Rolling Stones and The Monkees, were also invited along to join in the party atmosphere.

Having written the score, George Martin requested that a second J37 be used, so that the orchestra could be recorded four times, giving the impression of a 160-piece orchestra. To run the two machines in sync, technical engineer Ken Townsend devised a method of using a 50-cycle tone to drive the capstan motor of the slave machine. With The Beatles’ instruments and vocals on one J37 and the orchestra on another, the two machines had to be manually synced during mixing.

The final piano chord that ends the song was recorded as an edit piece, featuring John, Paul, Ringo and roadie Mal Evans playing a weighty E major chord on three pianos. This was overdubbed twice more and then a long, low harmonium note filled the remaining track.

Three new songs were introduced to the sessions in February. McCartney’s upbeat Lovely Rita and Lennon’s psychedelic Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds both used vari-speed techniques, recording audio at a slower speed to sound faster on replay. Many tracks enjoyed this effect, however, Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds was vari-speeded more than any other, including the distinctive keyboard intro played by Paul on a Lowrey organ.

The other new song was Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite!, the lyrics of which were taken virtually wholesale from a Victorian circus poster bought by John when the group were filming the promotional video for Strawberry Fields Forever in Sevenoaks, Kent. “Almost the whole thing was written right off this poster,” Paul recalled. “We pretty much took it down word for word and then made up some little bits and pieces to glue it together.”

To create the right vibe for the track, Lennon told George Martin: “I want to be in that circus atmosphere, I want to smell the sawdust.” Martin obliged by chopping up pre-recorded tapes of a calliope – a steam organ often heard at funfairs – and editing together random sections, some of them played backwards, to produce a swirling backwash of sound.

For the middle section where, of course, ‘Henry The Horse dances the waltz’, the group performed one of the most inventive overdubs of their career, recorded at half speed. John and George Martin played chromatic runs on Lowrey and Hammond organs, while George Harrison and roadies Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans puffed away on bass harmonicas.

Paul then contributed a lead-guitar line, played through a volume pedal to give a surging effect, while Martin doubled the line on organ and Ringo tapped a tambourine. When played back at twice the recorded speed and an octave higher in pitch, the effect was dazzling, further reinforcing the circus-like atmosphere.

Mics and mic’ing techniques

Former Beatles engineer Norman Smith used two mics to record Ringo Starr’s drums, an AKG D19c above the kit and an AKG D20 in front of the bass drum. Geoff Emerick continued with this arrangement for Revolver; however,for Sgt. Pepper… he added a further three D19s to close-mic the rack tom, floor tom and hi-hat. A Neumann KM-56 was placed beneath the snare drum.

Neumann U47 and U48s were generally used to record vocals although, occasionally, the smaller KM-54 and KM-56 microphones were employed. The KM mics were also traditionally used to record acoustic guitar, although for Sgt. Pepper…, Emerick began using a NeumannU67 for all guitars. The U67 was also favoured for most piano and keys, as well as orchestral overdubs.

Most of Paul’s bass parts were overdubs. His Vox 730 amp was mic’d with an AKG C12, sometimes set to figure-of-eight, several feet away from the bass cabinet. Emerick occasionally augmented this with a second mic or a DI bass. Photos from sessions show an STC 4038 ribbon mic alongside the AKG C12.

Slowly Getting Better

Getting Better, one of the simplest-sounding songs on Sgt. Pepper… was actually one of the busiest recordings, containing numerous overdubs and requiring three reduction mixes, more than any other Pepper song.

The vocal session on 21 March proved eventful, as attendant Beatles’ biographer Hunter Davies wrote: “They ran through the song about four times and John said he didn’t feel well. George Martin came down from his box (control room) and told John he would be better to go up on the roof and get some air, rather than go outside.”

Unbeknown to Martin, John had inadvertently taken LSD and was in the middle of a trip. Though the group’s use of mind-altering chemicals greatly influenced Sgt. Pepper…, they usually partook recreationally.

“I never took it (LSD) in the studio,” Lennon remembered. “Once I did, actually. I thought I was taking some uppers and I was not in the state of handling it. They all took me upstairs on the roof, and George Martin was looking at me funny, and then it dawned on me I must have taken some acid.”

Sessions continued throughout March, with the recording of Ringo’s vocal contribution to the album, With A Little Help From My Friends, written specially for him by John and Paul. For the mono mix, Ringo’s vocal was heavily flanged, while the stereo mix only received a small amount of A.D.T.

Two orchestral-based songs, Paul’s sentimental She’s Leaving Home and George’s Indian-influenced Within You Without You were addressed towards the end of the sessions, the latter featuring exotic instruments such as dilruba, svarmandal, tambura, tabla and of course, sitar. To lighten the mood, after what may have been a difficult listen for fans more accustomed to guitars and drums, the sound of laughter was added at the end of the track.

Mono versus Stereo

Originally released in both mono and stereo, the mono Sgt. Pepper… was deleted in the early 1970s, when stereo became standard. Although the stereo version is better known, the mono mix was considered definitive by The Beatles and their production team.

Tape op Richard Lush certainly believes so. “The only real version of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the mono version,” he stated in Mark Lewisohn’s Complete Beatles Recording Sessions book. “The Beatles were there for all the mono mixes.

Then, after the album was finished, George Martin, Geoff (Emerick) and I did the stereo in a few days, just the three of us, without a Beatle in sight. There are all sorts of things on the mono, little effects here and there, which the stereo doesn’t have.” John Lennon’s lead vocal on Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds is a good example of the differences.

The mono version features a psychedelic phasing effect; the stereo has Artificial Double Tracking. The mono mix of She’s Leaving Home was sped up at Paul McCartney’s request.

Wrapping up

The last song recorded was a reprise of the title track, recorded simply in one 11-hour session with no reduction mixes. While most of Sgt. Pepper…was recorded in EMI Studio Two, the Reprise was recorded in Studio One, usually reserved for large orchestras.

“After the final crashing piano chord of A Day In The Life faded, a 15kHz tone was added for the benefit of dogs”

“I think the reprise version of the song is more exciting than the first cut of Sgt Pepper…“, recalled Geoff Emerick. “There’s a nice quality about it. We recorded The Beatles in the huge Abbey Road Number One studio, which was quite hard because of the acoustics of the place. It’s difficult to capture the tightness of the rhythm section in there.”

As a finishing touch, after the final crashing piano chord of A Day In The Life faded (listen out for the squeaking chair and someone say ‘Shh’ during the fade), a 15kHz tone was added for the benefit of dogs, before some gibberish played into the run-out groove ad infinitum, or at least until the arm was lifted from the record.

Outboard Processors

Engineer Geoff Emerick always used the Fairchild 660 limiter on vocals and drums. Backing tracks and Paul’s bass were processed with the EMI-modified RS124 Altec compressor. With a fixed attack time and six-position recovery switch, the Altec had a unique Hold control. The RS127, known as ‘The Presence Box’, had three EQ settings – 2.7, 3.5 and 10kHz. A 10dB boost at 10kHz was a popular setting, particularly on drums. Reverb was mainly generated via Abbey Road’s echo chambers, but the EMT 140 plate reverb was also used.

EMI technical engineer Ken Townsend invented Artificial Double Tracking (A.D.T) in 1966. It created a delay time of around 40ms by recording audio onto both the J37 four-track and EMI’s BTR2 mono recorder. The distance between the Record and Playback heads on the BTR2 was almost double that of the J37, so with the BTR2 running at 30ips and the J37 running at 15ips, the two signals were replayed almost simultaneously. Interviewed about Sgt. Pepper… in 1967, John Lennon said: “Phasing is great! Double-flanging we call it. We’re always doing it. You name the (song) it isn’t on.”

A Divisive Masterpiece

Hailed as a masterpiece on release, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band has had a chequered critical history. Paul McCartney, whose fingerprints, more than any other Beatle’s, are plastered over the album, has never spoken ill of it – although the other members have, on occasion, spoken against it.

John Lennon dismissed claims for it being rock’s first concept album by insisting his contributions had nothing to do with any idea of Sgt. Pepper and his band; he also said he preferred ‘The White Album’. George Harrison complained about the lack of unison playing on the album, while feeling increasingly annoyed with Paul’s bossiness in the studio. Ringo, who had little to do once the initial backings were taped, said he learnt to play chess during the sessions.

Is Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band The Beatles’ masterpiece? It certainly took four-track studio recording to a new level and paved the way for the multi-track approach of the 1970s and beyond. Yet when placed alongside Rubber Soul, Revolver, ‘The White Album’ and Abbey Road, it’s difficult to rate any one categorically above the others. One thing is certain, to hear the album as The Beatles and their production team originally intended, the mono mix is the only show in town, and is guaranteed to raise a smile.