Twenty Arrangement Tips

Your grooves and melodies won’t mean a thing if they’re poorly structured. Get your musical house in order with Hollin Jones’s indispensable advice… 1: Use arranger tracks If your DAW has any kind of non-linear composition technology available, try it out when arranging. Logic Pro X has the Arrangement track, Reason has the Blocks system […]

Your grooves and melodies won’t mean a thing if they’re poorly structured. Get your musical house in order with Hollin Jones’s indispensable advice…

1: Use arranger tracks

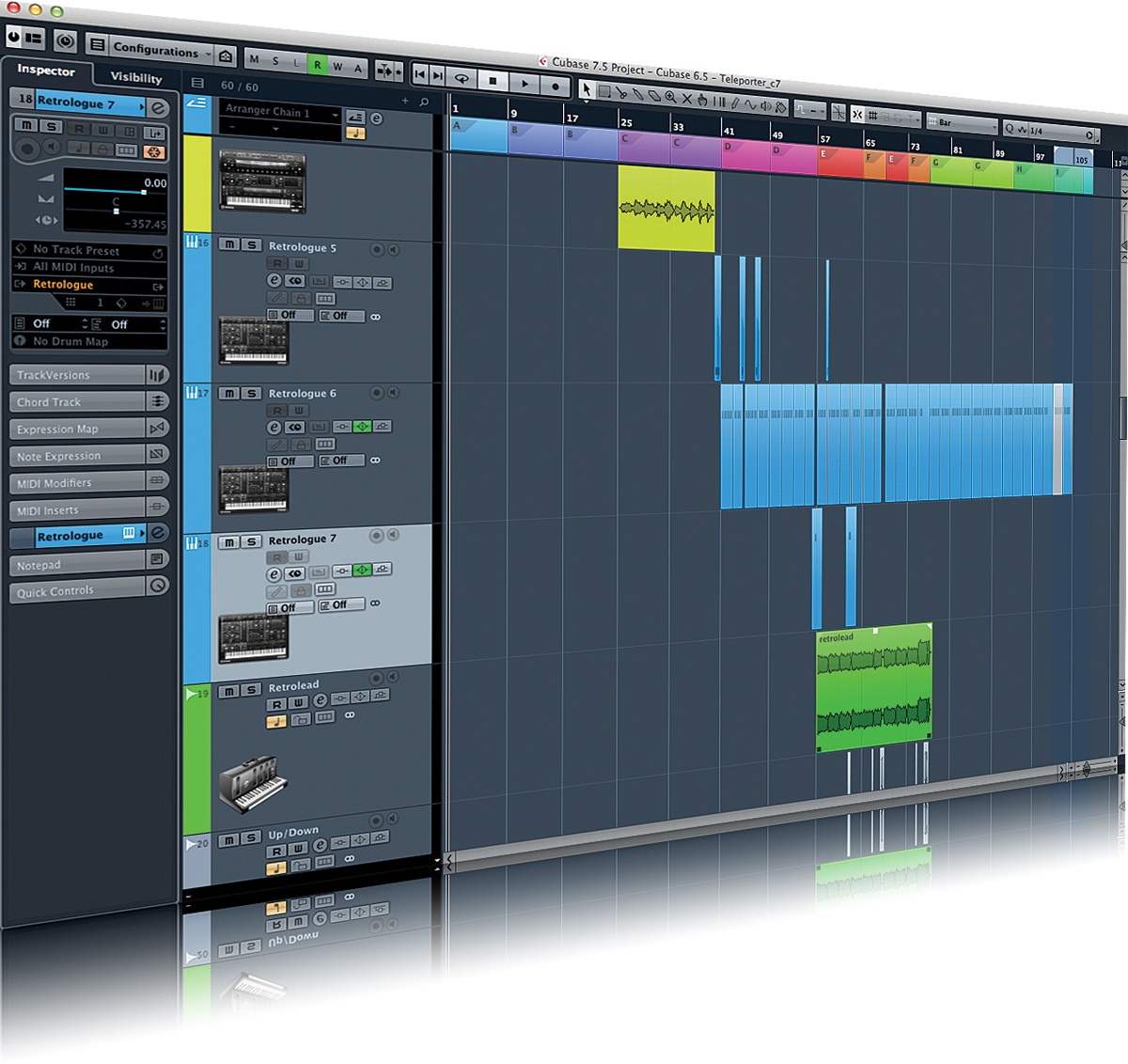

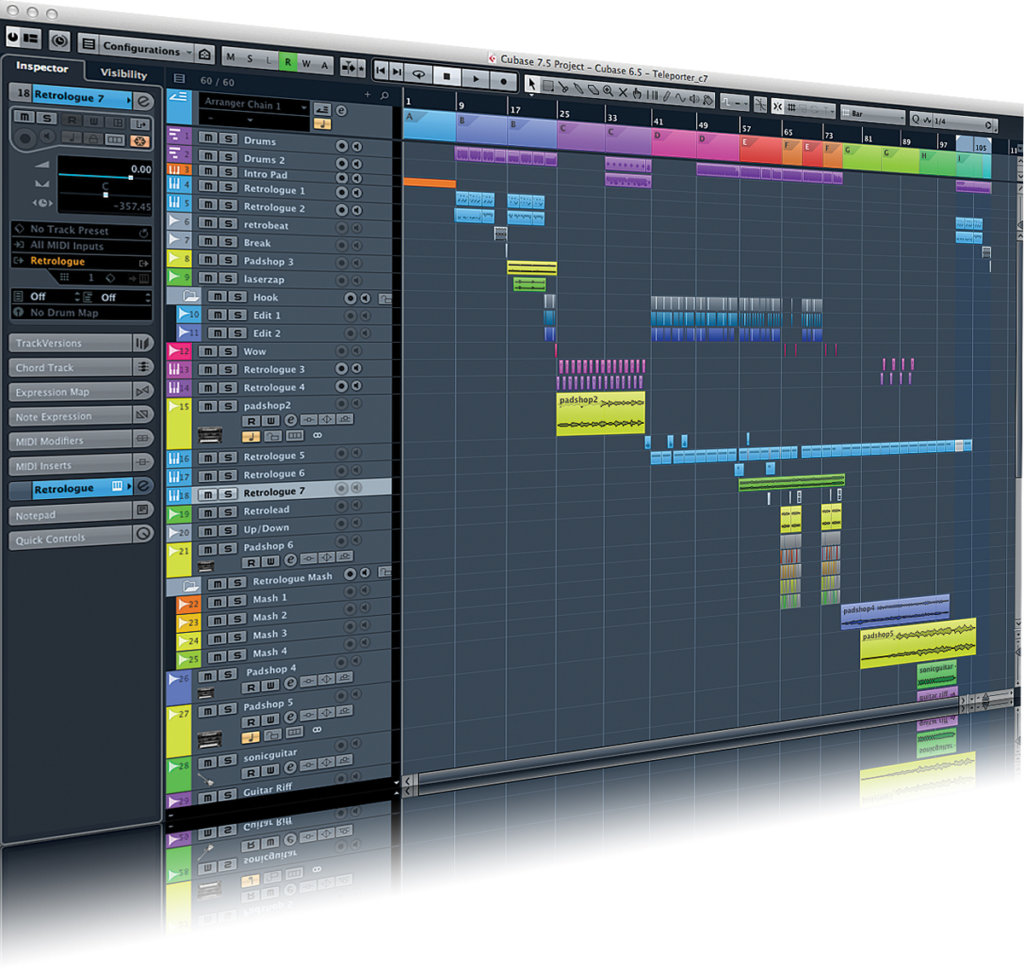

If your DAW has any kind of non-linear composition technology available, try it out when arranging. Logic Pro X has the Arrangement track, Reason has the Blocks system and Cubase has the particularly powerful Arranger track. All of these in some way enable you to build sections of music on the timeline and then specify a playback order for them that is unrelated to their actual position.

So for example you can tell the track to play back two instances of the intro section, four of the verse, one of the chorus and so on, in any combination. The ability to create multiple ‘virtual’ arrangements and hear them without having to actually copy and paste or shuffle anything around on the timeline until you have settled on an arrangement is really useful. Cubase even has the ability to render out multiple arrangements to new project files

2: Lock to a timebase

Always record to a click track, even if your music doesn’t involve any beats. DAWs are based entirely on the notion of material conforming to a timebase and use this for snapping, quantizing, slicing and all kinds of other things. While it’s possible to just record without reference to any kind of clock, this could cause you problems further down the line as, for example, it will make it much harder to remix your music.

Remixers like stems that have been recorded in time and that start precisely at a bar marker, and preferably have the BPM included in the file name or somewhere else prominent. DAWs let you quickly cut up, copy and paste and rearrange material but this is far easier to do if you’re not having to worry about stuff drifting out of sync or indeed not being in sync at all in the first place.

3: Make multiple versions

The way you arrange your track will depend on what your target market is. If you’re making a nine-minute experimental prog rock song, you probably aren’t too worried about it getting airplay on drive-time radio. Conversely if you’re writing stuff to pitch for adverts it needs to be concise and punchy. Modern technology gives you a huge amount of flexibility when it comes to arrangements, so your album version doesn’t have to be the only one you make.

Radio edits have been around for years: shorter, punchier forms of songs that cut out the long intro, the drum breakdown in the middle and other elements that make a track less likely to get played on mainstream programmes. Make a radio edit of longer tracks to increase the chances of them getting played. Also, always have a ‘clean’ edit if your track contains any swear words, and always keep a separate instrumental version for sync purposes.

4: Get to the point

It might sound obvious, but if you’re writing anything that’s designed to be catchy and memorable (as opposed to vague and experimental) it’s a good idea not to muck about for too long before you get to the hook. Some songs have massive choruses and the verses are really little more than filler – a less interesting bit that you have to get through so you’re even more ecstatic when the chorus returns.

That’s not to say your verses can’t be memorable and interesting, indeed they should be. But don’t have a three-minute build of ambient noise before anything happens, unless that’s specifically what you mean to do. Some bands trade almost entirely off the dynamics of their music – Mogwai are a good example – but it takes skill to make it work well.

5: Go non-linear

Most people are used to working in a DAW, and these encourage us to work with a linear left-to-right approach. Your project starts at zero and goes on for three, four, five minutes. This wasn’t always the case, and early sequencing tools encouraged you to build up sections of music and then link those sections together to form a song. Some software, notably NI’s Maschine, still works this way for its own internal song sequencing tools.

It’s almost a more mechanical way of working: you have two instances of this section, three of the next section, one of that part and so on. This approach can work particularly well for electronic music where there can often be more of a build up / build down approach than conventional songwriting with its verses and choruses.

6: Burn out or fade away

Knowing how to end a track is always a bit of a conundrum. The classic cop-out has always been to fade a track out, but increasingly producers are opting instead to actually think of a way to end a track. This is particularly important in the modern era where sync – using music for adverts or film – is increasingly important as a potential source of income for musicians.

Editors like definitive, manageable sections of music because it enables them to cut the picture to the sound much more easily. So even if your track doesn’t come to a dead stop at the end, consider having an alternative edit that does, or including a stop or two within the body of the track and a subsequent return of a big chorus or refrain. This will make a track more usable for sound-to-picture purposes.

7: Less can be more

Layering your mix is pretty vital to creating a full, rich sound that will entice the listener in. But it is also a real art form, tied in with the science of mixing. Modern software lets you have more or less as many tracks as you want in a project, and while that can be liberating (add an orchestra while working from a bedroom) it also provides the opportunity to go over the top if you’re not careful. Just because you can throw in 15 synth lines doesn’t mean you necessarily should.

Good arranging can be as much about what you leave out as what you leave in. While the production behind many classic records can be complex, the actual arrangement often isn’t. Sometimes less really is more, and you should be ruthless. Seek the opinion of a trusted friend or colleague if you aren’t sure whether something is working: it’s easy to lose perspective

8: Get with the times

This is a bit of a strange one, but if you listen to a lot of the non-electronic music that makes it onto the radio you’ll hear a curious number of whoops, whistles, claps and brass hooks. Although this seems to be a recent phenomenon it actually goes back years, and if you listen to old funk and disco records you’ll hear similar compositional tricks being used.

Introducing more of a human element, like the idea of someone clapping along actually within a track or whistling a chorus, has a psychological effect and enables listeners to connect with the music on a more fundamental level, whether they realise it or not. And although it may seem slightly over-simplistic to say “if you want to get airplay, include some hand claps or brass hooks”, evidence would seem to lend this idea a certain amount of credence.

9: Compose in sections

Although conventional songwriters will often work on a song in a very linear fashion there’s nothing to say that everyone has to do this. DAWs and other recording technologies enable you to think up and work on various different sections of a track in a non-linear way. So for example you might come up with an idea for a chorus first, then somewhere else on the timeline start to construct a couple of different ideas for what the verse could be.

Then later add fills or breakdowns and stitch the whole thing together, either using some kind of arranger track or by copying and pasting stuff around in the sequencer. DAWs generally use nondestructive editing, so even if you pitchshift one audio loop the others remain the same, making it safe to experiment with different treatments.

10: Randomisers can help

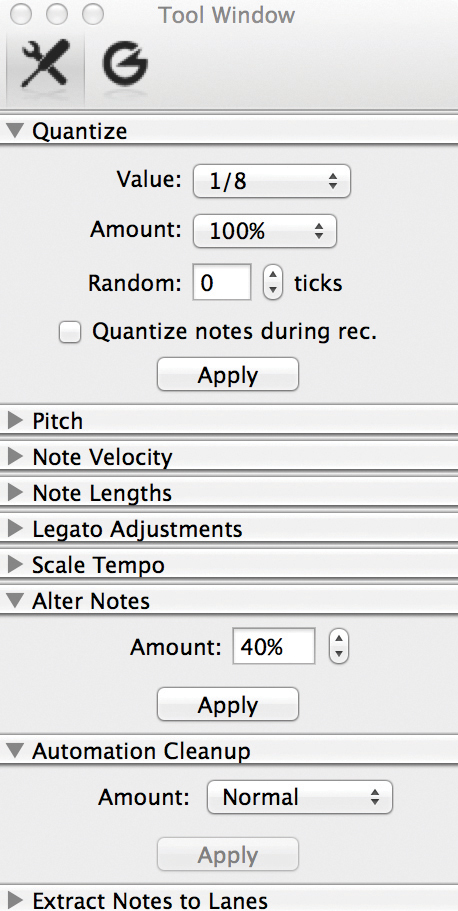

There are plenty of tools available to help you come up with new musical ideas – you’re not on your own when it comes to thinking of variations, beats or melodies. For MIDI parts especially there are usually options in your DAW to randomise notes within a clip, and these can often be set up to affect some parameters but not others; for example, to keep the timing of a clip but change the pitch of the notes.

This can cover everything from transposition to an arbitrary re-imagining of a part. Some tools will even come up with stuff from scratch for you, entering a random selection of notes or creating a whole new instrument sound by assigning values to a synth’s parameters or a drum machine. MIDI loops and audio samples are another good way to spice up your compositions if you’re lacking in inspiration.