Using felt piano creatively

Gently scattered among the scores of some of the most talked-about films and TV shows in contemporary media, felt piano comes in many shapes and sizes, and its DIY ethos has no end of big-name advocates. Here, we tread softly to uncover how the instrument is used to craft emotive soundtracks, and how you can make smart use of it

Despite the seismic advances in virtual-instrument technology and the increasingly diverse range of popular soundtrack styles throughout all manner of media, the piano remains an object of eternal love and devotion. The instrument plays an enormous part in everything from contemporary TV shows such as Broadchurch and 13 Reasons Why to countless independent and blockbuster films. But the piano employed in these examples is neither bright nor classical. It’s something softer, more delicate. Here, the composers deploy a thin strip of felt between the piano’s hammers and strings to unlock a more intimate layer of its identity.

Though the felt piano’s fresh application by bleeding-edge composers such as Nils Frahm,

Ólafur Arnalds, and Dustin O’Halloran might have you believe that this is a relatively modern variation on the instrument, the felt technique actually originates from the classical period, with such luminaries as Beethoven and Mozart even dabbling with its inviting and close sound. The application of felt effectively takes the internal dampening mechanics found within many upright pianos to the next level, and can even be applied to larger-sounding grand pianos, making their soft sounds more consistent across the range.

With the modern classical movement having repopularised the mellow and muffled piano, you can expect to hear its effects throughout contemporary media for years to come. One of the earliest artists to revive this age-old technique, however, went unnoticed by many.

Feeling chilly

In 2004, Canadian composer Chilly Gonzales released his jazz-enthused Solo Piano album, one of the earliest contemporary records to feature felt piano, to worldwide acclaim. The piano pieces were so popular that fellow Toronto native and up-and-coming rapper Drake sampled the entirety of Gonzales’ The Tourist on his 2009 breakthrough mixtape So Far Gone. Gonzales has since been added to the credits and has collaborated with Drake in the studio and on stage.

Look closely at Gonzales’ upright piano – which he once played for 27 hours and three minutes to break Guinness’s world record for the longest-ever solo concert – and you’ll see a layer of felt fixed to a rail above its hammers. Throughout his concerts, Gonzales swaps between felted and unfelted piano by pressing down on what’s usually called a practice or céleste pedal, a standard feature of upright pianos. His pedal is rigged to lower the rail so that, when he plays a key on the piano, the hammers hit the felt before the strings, dampening the sound.

The felt sound was a distinctive part of Gonzales’ Solo Piano record, and it came to the forefront of the emerging modern classical music scene in 2011 when German musician Nils Frahm used it at the heart of his breakthrough album Felt. Frahm reportedly turned to the technique because he needed a way to practise piano at night without waking his neighbour. Felt not only supercharged Frahm’s career and boosted the profile of the soft-piano sound, then, it also ensured that a Berlin resident got a good night’s kip. Heroic.

“The piano is more than a decade older now and, like great wine, she’s even fruitier”

Meanwhile in Iceland, Ólafur Arnalds, a composer and close friend of Frahm, was himself discovering the appeal of a softer sound. Though initially, on his Living Room Songs album, he used a cut-up T-shirt in place of a sheet of felt, the textile has since become a staple of his music. Judging by his BAFTA-winning soundtrack for Broadchurch in 2014 and his theme for Apple TV’s recent Defending Jacob series, it seems as if felt is beloved by showrunners too.

Now in vogue, the felt concept came to the attention of many in the music-production world when Arnalds and Frahm partnered with Spitfire Audio and Native Instruments respectively to introduce felt-piano virtual instruments.

“I went over to meet Ólafur and the composers that work in the same building in quite a fishy-smelling district of Reykjavík,” says Christian Henson, composer and co-founder of Spitfire Audio. “Upon entering Ólafur’s studio, I went, ‘Oh, one of us’. It’s something you learn to sniff out: fellow sound-smiths, people who care as much about sound as harmony and melody. The only way you can apply care to sound is to create it. It’s like a martial art – ‘Shit, this guy’s a black-belt!’ Our first connection was talking about our soft piano.”

Making magic

Gonzalez, O’Halloran, Frahm, Arnalds and other composers may have brought the felt sound to listeners across the world but it was Henson’s soft-piano samples that caught the ear of many actual music-makers.

“I recorded the piano that became Soft Piano, the free Labs virtual instrument with the céleste pedal, as part of my score for the film The Secret of Moonacre,” says Henson. “I loved the sound so much that I sampled it in 2008 and we gave it away as part of our initial Labs project in 2011. A large chunk of the 4.5 million downloads of our free Labs range can be attributed to the Soft Piano.”

Henson still loves that original sample collection. “It’s so weird to remember so clearly that hour I spent recording it at Air-Edel Studios all those years ago,” he says. “Noise reduction wasn’t as good then as it is today, so we’d already done a pass with some of their incredible valves and then I got scared and did a pass with the Schoeps mics that you hear today.”

But that was just the beginning for this soft-piano sample. Almost 10 years on, Henson and his colleagues at Spitfire tracked down the same piano to re-record it in Lyndhurst Hall at AIR Studios for their Originals range.

“It has the same magic,” he says, “which, combined with the magic of the hall, is something else. But the piano is more than a decade older now and, like all great vintage wines, she’s even fruitier.” You can get a free sneak peek of that sample library as part of Henson’s Pianobook project (pianobook.co.uk), a community-led website through which composers share their samples.

Double-take

Dustin O’Halloran was another forerunner of the modern classical scene, thanks to his abundance of solo piano albums and his collaborations with Adam Wiltzie as A Winged Victory for the Sullen. In recent years, he has formed another successful duo, composing for the big screen with prepared-piano player Haushka. The pair were nominated for an Academy Award in 2017 for their soundtrack to the biographical drama Lion, the heart of which was the piano – but not just one of them.

“We recorded the main theme that opens the film on a Steinway in Los Angeles, in this really nice room,” says O’Halloran. “We wanted it to have a rich bass and a really open sound. The opening scene features these slow-moving images of Australia and India from above. They were landscape shots, so we wanted things to feel really open. But, as the

story gets more and more intimate, we move onto more felted and more intimate-sounding pianos.

I don’t think you’d get the same intimacy on a grand. That’s what’s really nice about an upright – everything’s a little bit closer, the strings are a little more humble. It’s kind of nice to take a piece of music and use the different pianos as a variation

of a theme.”

Where the heart lives

“The piano can be very attack-heavy if you don’t know how to treat it right,” says Brendan Angelides, also known as Eskmo, and Welder, the composer behind the soundtracks to such series as Billions and 13 Reasons Why. “The softer felt mid-tone, that’s where the heart lives, and then the top stuff kind of sings.”

Felt revolution

In early 19th century Vienna, Conrad Graf was renowned for the grand pianos he built for the likes of Beethoven, some equipped with as many as six pedals.

One of these was called the moderator, which featured a rack of cloth sometimes two layers thick that moved horizontally between the piano hammers and strings, initially used with a sustain pedal to imitate the sound of a harmonica.

Beethoven, Haydn and even Napoleon all received pianos from Sébastien Érard,

a prominent builder based in Paris. He introduced a version of the softening system for upright pianos using leather and called it the jeu céleste, which means celestial, heavenly game. While Beethoven regarded it as a novelty feature, later composers, notably Schubert, used it during quieter passages of their pieces.

Tutorial: Close mic’ing a felt piano

1. On most upright pianos, the lid can be opened up or removed entirely. The upper panels often feature hooks on both sides or some other mechanism that must be detached to do so. Be aware that the lids can be heavy, so this might be a two-person job. Removing the music rack and key cover is a simple case of unhinging and lifting off too. This isn’t usually essential but can make felting and recording easier.

2. Source some felt from a crafts shop or online or, alternatively, cut up an old T-shirt or blanket into one or two long strips. Depending on your piano, you may want to experiment with different felt thicknesses or double up on your T-shirt, blanket or material of your choice. Use some masking tape to secure your material to the top of the piano or weigh it down with some light objects so that it doesn’t slip away from the hammers.

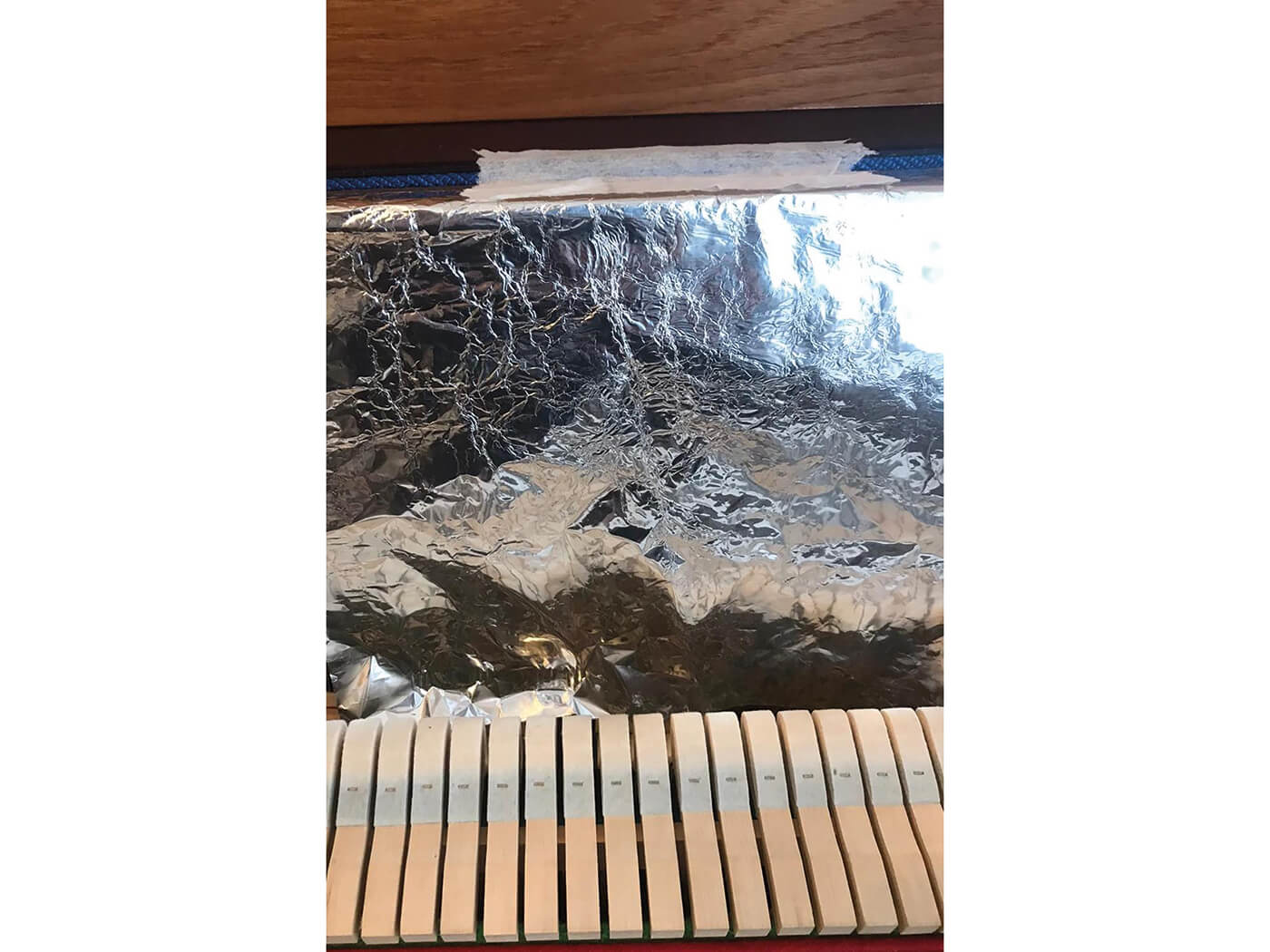

3. You can also experiment by placing paper, tinfoil or gaffer tape over some of the strings. These prepared-piano techniques can be particularly effective in the upper registers. Use masking tape the protect the piano’s varnish where necessary.

4. Set up a pair of matching condenser microphones close to the piano hammers and felt to capture the intricate mechanical noises. Here, we’re using Røde M5s running through a Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 to record the left microphone into the left input and right microphone into the right input.

5. The closer you position the mics, the more hammer and mechanism noises they’ll capture. Position the microphones about a foot away from the hammers and a few feet away from each other to record the bass and treble. Of course, your measurements will depend on your piano and microphones. Testing your mic placement using your ears is the best way to perfect your setup.

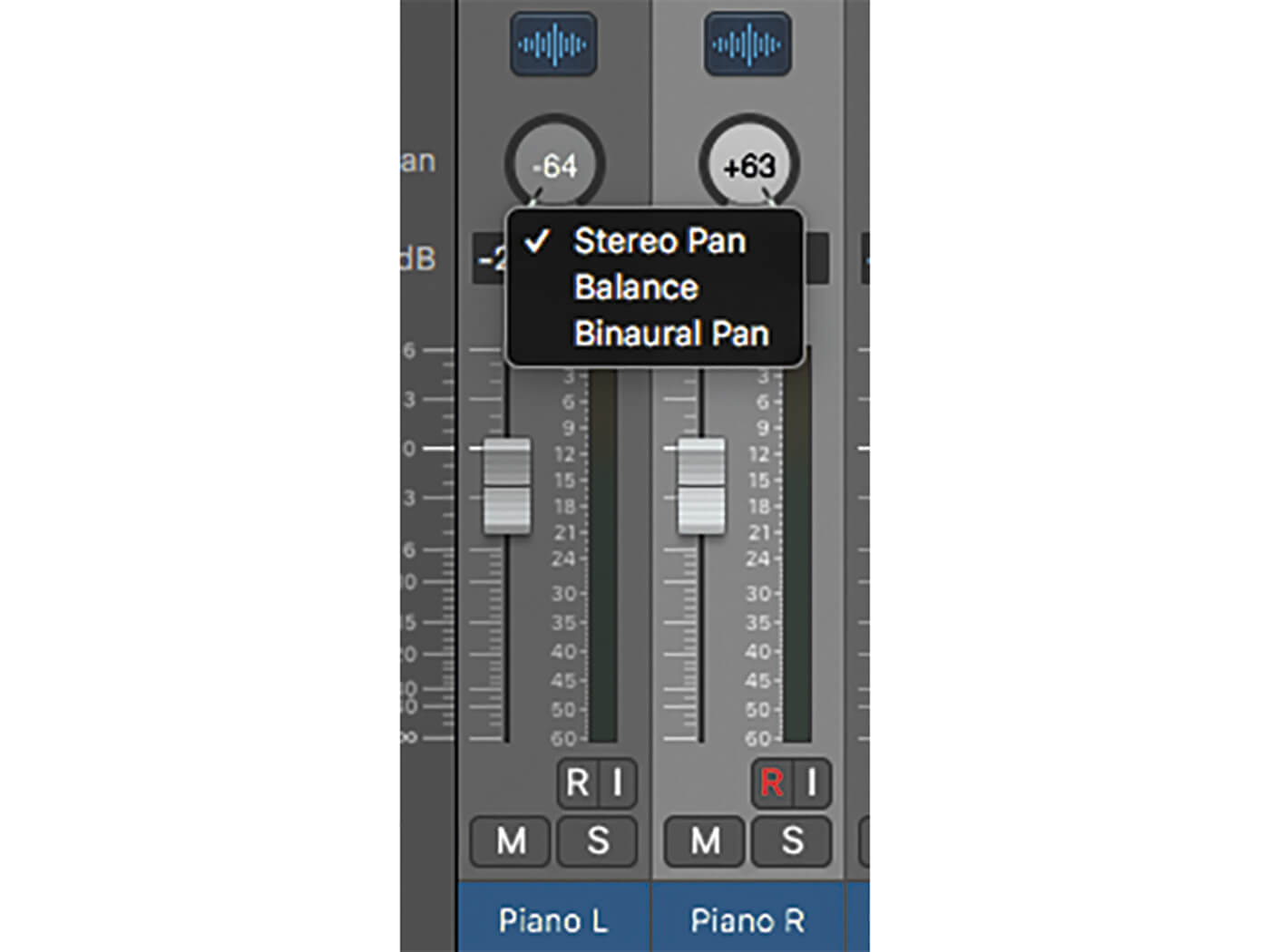

6. With your solo piano piece successfully recorded into your DAW, it’s time to get to work. If, like us, you’re using Logic Pro X, remember to select stereo panning instead of balance. Now, panning the left channel hard left and the right hard right will create a strong stereo effect, emulating what the player hears when they play.

Before beginning the score to 13 Reasons Why, Angelides got a small piano in his studio. It became an integral part of the soundtrack as he experimented with techniques such as making the top end reverb-heavy. “That, combined with synths that just ring out for a really long time, on top of the more felty mid-tone, created a balance of magic and wonderment,” he says. “Just playing with the angles of the mics and playing with different layers and degrees of felt can change a lot. I’ve also messed with adding aluminium foil and pieces of paper so that some keys kind of ring off.”

Hyper-real emoting

“Back in the early 2000s, it seemed that every film composer wanted to emulate the sound of Michael Andrews’ piano on his cover of Mad World for the Donnie Darko score,” says Henson. “With that arrangement, it’s like your head is inside the piano. It sounds so insanely personal.”

Even though Andrews’ piano might not have featured felt, Henson says that, by employing the material, he was able to get a little closer to Andrews’ sound. “That made me very excited. For me, what the soft, felt, céleste sound offered was an understated aching beauty that matched modern acting styles, where people do not emote in a theatrical manner but almost in a hyper-real and hyper-quiet murmuring style”.

“Every film composer wanted to emulate the piano sound on the Mad World cover”

O’Halloran agrees. “Films usually feature dialogue. Sharp, unfelted pianos are in the same range as the voice, and so they can fight with it,” he says. “But felted pianos remove some of the frequencies that fight with the voice. Sometimes I’ll try a piece on a grand and it’ll be too punctuated. There’s a blurriness to felt that can be really nice for music. Other times, you need the clarity.”

Ever felt this way?

So what are the key attributes of recording and using felt piano in your tracks? “It can take away some of the overtones and kind of adds a natural compression,” says O’Halloran. “For close mic’ing, it’s more forgiving. It’s like these early crooner recordings from the 1950s, where they got really close to the mic but sang really softly. If you’re playing really dynamically with no felt on a close microphone, it’s not nice to listen to. That’s why classical recordings have big rooms and they put their mics far away, because the dynamics of classical recording are extreme.”

But what if this more muffled piano sound gets lost in the mix? “Half the fight of composition is knowing the frequencies you’re using and noticing when you’re doubling up on them. If you’re using felt, the mid-range frequencies are going to be well represented. If you write your violin a bit higher and your bass a bit lower, you’re giving space to everything.”

“Half the fight of composition is noticing when you’re doubling up on your frequencies”

Angelides uses a canny production technique to ensure that his felt piano remains audible and perfectly placed in his mixes: he rigs competing elements to duck out beneath the sidechain input of the piano. “For example,” he says, “if there are low-mid pads, as well as some delicate strings and piano – never mind any percussion – I’ll make sure to have other things gently duck out using a FabFilter Q3 or some other type of simple frequency-orientated sidechain. I sometimes give it a gentle boost in the area from 7kHz to 14kHz, just to give it a lift, so you can still have something mellow but that can pop through the mix.”

For music-makers intrigued by the felt concept but who lack access to a piano, the free samples available via Henson’s Pianobook project make for

a fine starting point. Combining sample libraries can also help create unique-sounding software pianos. You could, for example, mix the mechanical noises and softer tone of Native Instruments’ Una Corda with the brighter and quicker attack of the Giant. Plus, most of these sample libraries now allow users to tweak the hammer, dampener and even pedal noises to emulate the intricacies of close mic’ing, the favoured recording technique for felt piano.

The felt sound remains a prevalent aspect of modern scores and arrangements. You’ll hear soft close-mic’d piano on the recent collaboration between Billie Eilish, Finneas and Hans Zimmer on the theme to upcoming James Bond flick No Time to Die. It’s fair to say the sound has come a long way since Arnalds’ cut-up T-shirt. He also tried placing a beer bottle beneath one of his piano’s pedals to keep the hammers closer to the strings, though this technique hasn’t quite caught on – yet.

For more features, click here.