Get Paid For Your Music – The Ultimate Guide

Fact: you’re more likely to make a decent income from sync music – that’s music in film, TV and video games – than you ever will with chart fame. Another fact: it’s easier than you might think to get into. Rob Boffard has the advice and the contacts you’ll need… There are a lot of […]

Fact: you’re more likely to make a decent income from sync music – that’s music in film, TV and video games – than you ever will with chart fame. Another fact: it’s easier than you might think to get into. Rob Boffard has the advice and the contacts you’ll need…

There are a lot of names for library music, such as sync, production music, stock music… In general terms, it refers to the use of music in TV and film, in video games, on the radio, in online videos –anywhere that requires a little dose of music to shine. But irrespective of what it’s called, it remains one of the most underused weapons in any producer’s arsenal – and a good way to make additional income from your productions.

A single hit can make a musician’s name; think about the use of Imogen Heap’s Hide And Seek in the television series The OC. And anyone can make library music (we’re going to stick with this term for now to avoid confusion), so although there are a few things to bear in mind, you’re not going to be using any production techniques that differ from what you’re doing already: chances are that you’ve already made some music that could work in a library, and which would also be quite comfortable sitting under the credits of a hot new TV series.

Of course, there’s also bad news – when you’re trying to make a living from music, there’s always bad news. While it can be a nice way to generate income and cement a reputation, cracking the library music safe is a very tough job. You’ll face immense competition, a massive industry that can often be rather set in its ways, and – like any producer – you’ll often have to fight to get paid! More importantly, you have to get used to the fact that once your music is being used, it’s no longer your own. You’re not releasing a track under your own name; it’s going out under the name of a production company.

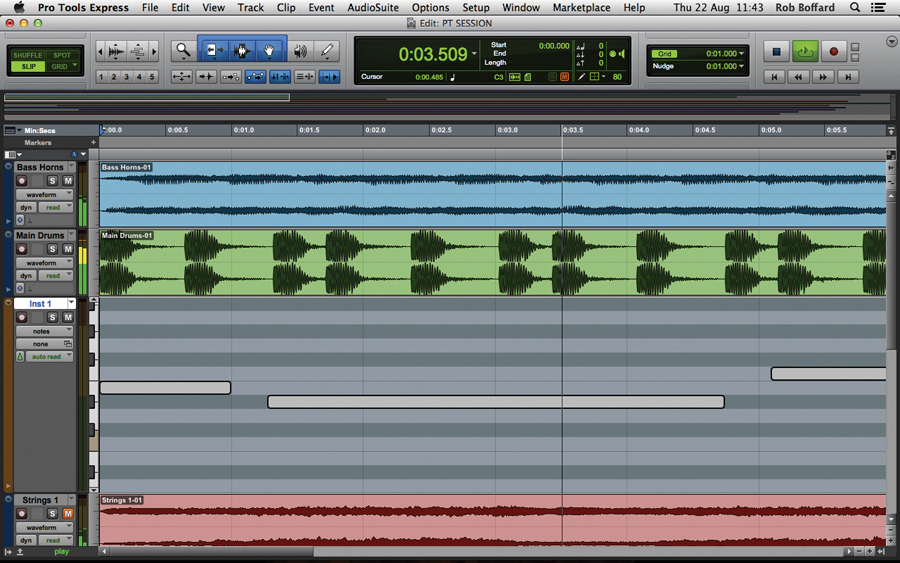

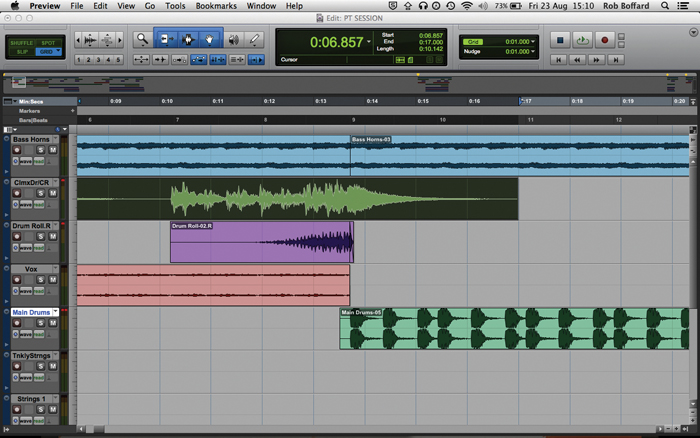

In this feature we’re going to walk you through everything to do with library music – how it’s made, where it’s used, who uses it (and why). We’ll chat to composers, library owners and music supervisors, finding out what they do and getting their tips on how to get called back again and again. We’ve also built our own library track from scratch – a classical monster that would quite happily work in the credits sequence of any Viking or crusader film. We’ll use it to break down the things you need to remember when creating a library track, including how to create shorter versions and how to separate out stems, and at the end, we’ll turn it over to a music library to see whether it passes muster.

In Process

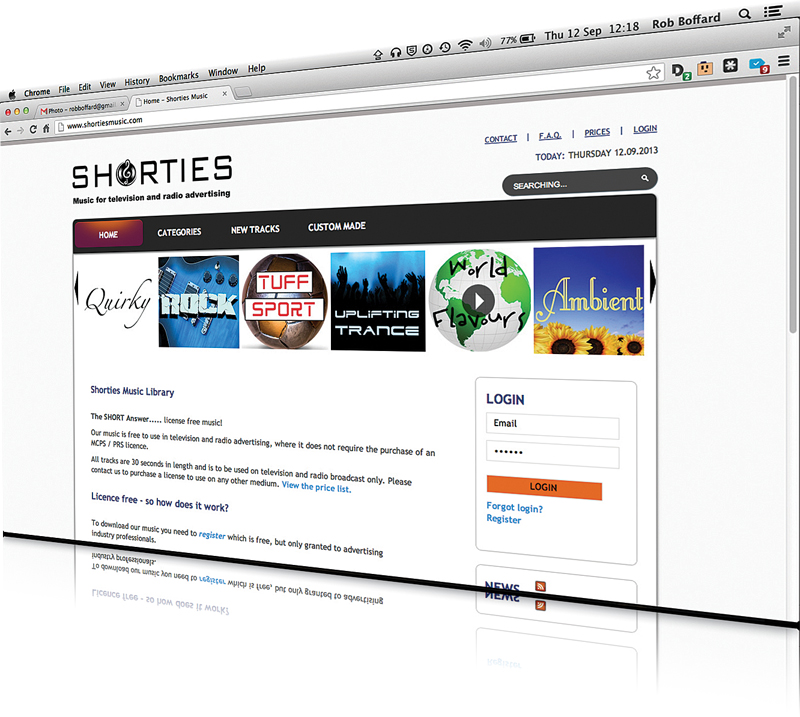

Let’s say that you want to get in on the library-music game. You’ve got a bunch of tracks together – a good demo that shows off your versatility and musical chops. First step is to find a home for it. In most cases, that means going to a music library, which is where the term gets its name from. A music library is just that: a library of music, sorted by styles, tempo, length, keywords and whatever other metadata can be dreamed up. Today, nearly all library companies are online, although quite a few still create CDs of music to send out to industry contacts.

If it works out well, the library bigwigs like what you present, and offer to put you on their roster. That means your tracks will appear on their website, available to listen to. Maybe they ask you to make more, or focus on a specific style that they can hear you’re good at.

Someone hears your track and likes it. They contact the music library and ask to license the track – ie, to purchase its use for a specific purpose. Depending on what the track is being used for, you could end up being paid a few quid – for the use of a track in a small radio ad, for example – or a hell of a lot of money if a company like Electronic Arts wants it for the next Dead Space (very unlikely, we should point out, but nonetheless a possibility!).

In addition, you’re also paid by the MCPS/PRS (Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society/Performing Right Society). They’re the organisations that collect money when music is used, and if they’re doing their job, you’ll get paid there as well. We’ll deal with them in more detail a little later.

They may want it exclusively, or they may want you to tweak a few things. If you become well-known enough, companies may begin asking specifically for your services. Music supervisors – who are in charge of selecting music for film and television – may commission you to produce something especially for them. You may be signed on a freelance basis to work on a particular project. Sometimes, music used in this fashion may have nothing to do with a library at all – it could simply be a piece of your music that someone has come to you to use.Very obviously, this is an extremely simplified version of what actually happens, but, in general, that’s how the industry works.

Click Here to read our guide to Building a Library Track

It’s a Demo

You might reasonably ask the question of why you should have a library representing you in the first place. Think of this like writing a novel. The music libraries are like literary agents: they form the middlemen between you (the writer) and the people who’ll use your music (the publishing company). They have the industry contacts, know-how and sales expertise you might not have. You have the musical skills they need.

Don’t be overly ambitious when starting out as you’ll need first to build a profile and get your name known

Putting together a demo of your material to send to potential music libraries isn’t as easy as slapping a few tracks together and firing them off. There are a few key things to bear in mind. Remember: libraries get tracks from producers all the time. Their inboxes are full of the stuff. To make yours stand out, there are a few things that you’ll need to do.

You need to spend some time finding the right libraries for you. Before you even think of submitting, you should know who their clients are, what styles they offer, and how you could fit into their roster. In addition, make sure that you’re aware of current trends within the industry – if you plan to write music for national radio ads, you should be listening to as much national radio as your time permits.

When getting your tracks together, you should aim for nine to ten tracks that showcase a wide variety of genres. If you produce only electro-house, well, good for you, but it really narrows down what you can do with your music. If, however, you’re confident with your DAW and your instruments and you can put together music from a wide variety of genres, you’ve already made huge strides towards getting noticed.

A busy producer is likely to spend very little time flicking through your tracks. Keep them short and make sure that the main ideas and audio elements are communicated right away. You want anyone listening to have a feel for the mood, style and temp of your tracks within seconds of clicking play.

Put your songs online – somewhere like SoundCloud is ideal. It should be a single place where someone can access the music you want them to hear. Beyond that, all you’ll need to do is write a friendly email (personalised, not blanket, if you please) telling why they should check you out and what you’ve got to offer. This is a good time to mention those industry trends you looked up earlier.

Find a reliable and flexible internet service provider to host a website that readily adapt and grow should your music prove popular

Gettin’ Money

Licensing laws and procedures vary from country to country. While every country will have an organisation dedicated to helping you get paid, we’re going to focus on the UK in this feature.

The Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society and the Performing Right Society have done their very best to merge into a single body accessed through a single website (www.prsformusic.com), but try as they might, they’re still dealing with two different types of bringing in money from music, and untangling who pays you what, when and how much can often be frustrating.

Definitely consider signing up with the PRS part of the programme. There’s a small fee – around £30 – to join up. PRS collects royalties for performance every time a track of yours is played; the amount varies depending on when and where this happens. They pay out quarterly, and you have to have a minimum of £30 in royalties before you can get paid.

The MCPS is somewhat trickier. They deal with what happens when your track is reproduced – recorded onto CD, say, or downloaded online. They have a different set of rates and payout schemes from PRS and they also collect the mechanical fee – the fee paid to license the track – and distribute it to the publisher and writer (the library and you). This is then split, depending on what you’ve agreed with your particular library.

Not all libraries are signed up to MCPS: some, such as Synctracks (which we’ve spoken to elsewhere in this article) are PRS-only. It’s worth checking very carefully what arrangements your library has before signing over your music to it. And of course, if you don’t actually go through a library – if, for example, a TV producer has sought you out directly to get one of your songs on their show – then you’ll almost certainly be paid a flat rate, along with royalties from PRS in those quarterly segments. In addition, some libraries specialise in royalty-free music, which lets users download a track for a one-off fee. For these, obviously, you can expect a single flat rate.

Finally, don’t expect to get paid immediately. It can often take months to see any of the money. Bottom line: if your track is sold you will get paid, but don’t expect to write a track this month to pay the rent next month. That just ain’t gonna happen…

Click here for our guide to creating different length versions

Taking Ownership

It’s worth stressing a point we made earlier: once you sell a piece of music, it’s no longer yours. Your name will appear next to it on the library-music website, the person who picks it will know who made it, and if there are credits on whatever it’s appearing on, it’ll pop up there as well. But once it’s bought? Forget it. You no longer have ownership.

Psychologically, this can be quite difficult to process. After all, you made the thing – as obvious as that sounds – and why shouldn’t you take credit for your hard work? But for whoever hears the finished product – whether it’s a radio ad, film score, TV series or whatever – is not going to associate that piece of music with you. You think that people watch the opening credits of TV series Suits and think of Ima Robot, who produced the disgustingly catchy Greenback Boogie that underscores it? You are divorced from whatever happens after your music is picked up. For everyone but Ima Robot, Greenback Boogie is the Suits song.

There’s a corollary to this: if your song is particularly good, you will suddenly find yourself deluged with curious fans who are Googling the theme song of whatever you’ve made it onto, hoping to find it and add it to their collections. While it’s certainly true that in most cases the song in question was never designed as a piece of library music – usually it’s an existing piece of music an artist or band has put out already – there’s nothing to stop the right piece of music from taking off. This is quite rare but it does happen, and you really want to be around when it does – your fan base can explode literally overnight.

The MCPS/PRS will sort out the financial side of your library work, but actually getting the cash in your pocket can take time, so be prepared to wait and don’t peg your dreams on seeing and immediate return

Range of Samples

Making library music demands not only a high level of quality, but speed as well. You need to be able to create a variety of tracks in a very short space of time. To that end, you should equip yourself with a huge range of weaponry. You should already be comfortable producing using a number of different synths and software instruments and know your DAW like you know your front door.

Sample libraries are a great way to add quality and, more importantly, diversity to your sound. They come in a huge range of flavours, and while we’d love to say you should get as many as possible, they can often be quite expensive, so what we’ve done here is highlight a few of the better options. Any or all of these will immediately set your productions apart.

Click Here to read our interview with film and games composer Chris Green

Companies such as Loopmasters and Prime Loops are often perfect for this – once you’ve bought sounds from them, they’re completely free for you to use from there on. They have an absolutely enormous range of collections to choose from and are often very reasonably priced.

The wonderfully named Violence, by Vir2, will give you some fantastic string sounds to work with. And we’re not talking traditional sounds here – the guys at Vir2 took string instruments and did some very unusual things to them, resulting in a library brimming with different textures, hits and stabs. The presets in Violence are absolutely extraordinary, and you can also tweak a whole bunch of effects to adjust the sounds to suit your needs.

Click here to read our interview with library owners Liz Robin Williams and Mikey Panting

For drums, Wave Alchemy has put together a great (and relatively cheap) library of synth drums called – wait for it – Synth Drums. Ten synths from companies such as Sequential Circuits, Roland and Korg have been sampled and are ready to go. There are more than 5,000 drum hits here, and although they’re all electronic sounds – don’t expect acoustic stuff in this collection – they’re very versatile and will find a home in any of your tracks.

For something really out-there, we’ve fallen in love with Glass Works, by Soniccouture. Among other things it captures the sound of cloud chamber bowls – an instrument so rare that they had to build their own to record it. The textures on offer are nothing short of breathtaking, and if you have Kontakt, you’ll find that Glass Works slots right in. It’s a little bit pricier than some of the other options, but we think it’s well worth checking out.

All of these options are royalty-free. Whatever you use, you need to be absolutely sure that this is the case. If not, it could come back to bite you later on…

Click here for our guide to seperating stems

Back Catalogue

You also need to pay attention to the matter of exporting, which can be a real headache if you aren’t managing it correctly. When you’re showing off your wares to companies, you can probably live with 320Kbps mp3 files – it’s high-quality enough to show off what you can do while still remaining portable.

Click here to read our interview with music supervisor Amanda Street

When it comes to delivering the real thing, however, you’ll need to make sure you’re clear about what your library expects. Most people we spoke to said that WAV files, delivered at 24-bit and 48kHz, are the standard way of doing things. You should be delivering both a full-length version of your track as well as 30- and ten-second versions. Once you’ve sent a track to your library there’s no harm in archiving the session on two hard drives somewhere (always keep multiple backups). Just make sure it’s easily accessible in case changes are needed.

Music libraries live and die by how easy they make it to find material. Producers and music supervisors looking for a specific track are far more likely to use tracks from a library if they can easily find what they’re looking for. Most libraries tag their tracks with a range of data – and you should too. DAWs such as Pro Tools let you add metadata and tags to your bounced-down files, and if you need more organisation, you can always check out programs like Jaikoz, which help you sort and tag your audio files. If you’re a Mac user, the latest version of OSX, Mavericks, allows you to add tags to files. Consider tagging audio by tempo, style, mood, genre and even specific instruments.