Extreme Audio Processing Tutorial

We take the ability to process sound in almost infinite ways somewhat for granted these days, but it’s not always been possible. For many years – and still,a in some circles – the cleanest take is what you’re aiming for. For other people, though, ‘extreme’ is just a lot more interesting. Starting with distorted guitars […]

We take the ability to process sound in almost infinite ways somewhat for granted these days, but it’s not always been possible. For many years – and still,a in some circles – the cleanest take is what you’re aiming for. For other people, though, ‘extreme’ is just a lot more interesting.

Starting with distorted guitars and moving on through white noise, the Loudness Wars, old-school sample-manipulation and mash-up plug-ins to dubstep and sidechaining in dance music, there’s more extreme sound processing around now than at any point in the past. This is partly, of course, because there are more tools to do it and more sub-genres of music. But it’s also because there’s something appealing about taking sounds and messing them up. There’s plenty of clean-sounding music out there and there always will be, but processed sound, be it glitch, white noise or ear-bursting electronica, will always interest some people more. Perhaps it’s because it sounds heavier, more intense or more gutsy, but it’s definitely on the rise.

The good news is that thanks to modern technology you can get in the act too, taking advantage of techniques both old and new to create extreme sounds in your own studio. The flexibility and convenience of digital audio coupled with the incredible power and functionality of plug-ins open up new worlds of sonic possibility, while the good old-fashioned technique of running sound through old speakers and recording it with microphones can also yield equally excellent results. All you need is a little know-how.

Down And Dirty

One of the biggest leaps in the history of music was the invention of electric instruments that required amplification rather than relying on pure acoustics to generate sound. Not only did the electric guitar and amplifier change music forever, they also meant that, for the first time, people could create sounds that had never existed before through a combination of pickups, amps and speakers. It was also the first time that anyone had managed anything resembling extreme sound processing.

Although it might seem tame now, the overdriven, distorted sound of the electric guitar was revolutionary at the time. Initially discovered almost by accident, distortion tended to be a result of equipment being pushed beyond the limit of its design, or being used after sustaining minor damage. Musicians realised, however, that this new sound was very appealing – immediate, edgy and fresh. These are the same reasons that people are still drawn to new, extreme sounds like dubstep or glitch; they’re just a different generation.

Blues and rock‘n’roll players in the 1950s started to deliberately drive their equipment to the limit in order to get a harder, grittier sound. Some people went even further, with legendary guitarist Link Wray apparently manipulating his amplifier’s vacuum tubes to create a noisier sound, and even poking holes in the speaker cones, resulting in the distinctive guitar sound that can be heard on his 1958 track Rumble.

In the 1960s, the distorted sound became commonplace, as more and more bands started to initially build their own guitar pedals to overdrive the signal. Eventually, commercial models began to be developed, among the first of which was the Maestro Fuzz Tone, released in 1962. In 1966, Marshall began to actively tweak its amplifier models to enable them to achieve a bigger sound and a fuller, brighter distortion. By the early 1970s, hard rock bands like Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and Black Sabbath were paving the way for what would become heavy metal, a sound created through the use of very high volumes and lots of heavy, dense distortion.

Camel Audio’s Alchemy runs on your desktop or your iPad and is able to take multiple sounds and morph between them in real time to create completely new noises.

Bringing Dirt Up To Date

Extreme processing would never really fall out of fashion in the guitar world, and went on to be used in all manner of different sub-genres of guitar music. Shoegaze bands such as My Bloody Valentine and, later, post-rock bands like Mogwai, would make white noise a feature of their sound, layering wave upon wave of feedback through endless effects to create a wall of noise. MBV in particular were known for their ear-splitting live shows. At the less extreme end, Spiritualized incorporated some pretty loud stuff into some of their early albums, a cacophony of drums, crunchy guitars and organs. In the early 90s, the whole US grunge scene – and later the indie scene – was powered by heavy guitar sounds.

As musical styles split and changed, the love of the extreme didn’t fade. Doom metal bands like Boris and Earth play drone rock; hardcore punk and metal bands are forever escalating their noise levels. Metallica’s St Anger album represented the pinnacle of how loud things could get – a record mastered so hard and so loud that people returned it to the shops because it was draining to listen to (an example, perhaps, that there is a limit to what people can take sonically, if not stylistically).

Bands like Nine Inch Nails plied a more experimental kind of heavy music, broadly known as ‘industrial’, incorporating more synths, samples and processing and rather fewer guitar freakouts. So why the love of heavy sounds? To answer that you probably only have to go to a good gig and see the difference in the way that the crowd reacts to quieter songs and to big, heavy, fast ones. Loud, gritty sounds are more visceral, somehow more serious. For some people that holds great appeal.

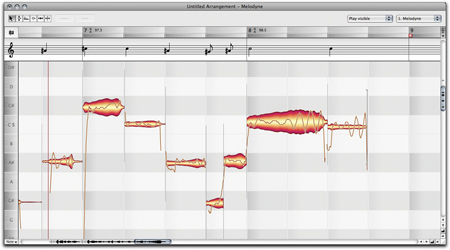

Advanced apps such as Melodyne enable you to reach inside polyphonic audio to make any edits you like.

Studio Techniques

Heavy, distorted guitars and sheer volume are, of course, just one form of extreme sound processing, albeit the one that’s been around for the longest. However, the advent of analogue tape also represented a big step forward in what was possible, since unlike the vinyl recording it superseded, tape could be speeded up, slowed down, chopped up and stuck back together. You might argue that vinyl is just as flexible, but of course people didn’t start to scratch and beat-juggle until at least the late 70s. Bands such as The Beatles, in their later and more experimental stages, played around with looping and varying tape speeds, then re-recording the results. It was in its own way the precursor to the kinds of production tricks that would become much more commonplace decades later with the advent of digital sound and its inherent flexibility and malleability.

As we’ve already mentioned, DJs in the late 1970s began to take old funk and disco records and cut them up using turntables, with pioneers such as DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash inventing concepts such as the ‘backspin’ –commonly heard to this day – and ideas like beat-juggling and scratching. Although quite different from what may traditionally be thought of as extreme audio processing, it is arguably a prime example, with source material being manipulated in real time, changed, mangled and mashed to fit the DJ’s desires. Even simply playing a record at a faster or slower speed than it was intended to be played at is pretty heavy.

DJ’ing has become an awful lot more complex since those days, and turntablists are now able to scratch mp3s, live DAW projects and other sources using timecoded vinyl and apps like Serato Scratch. NI’s Traktor Pro lets you route a mic or other source into your set live and process it through the same effects you can use to tweak and shape the sound that’s coming from the decks.

Marshall was one of the first companies to build amplifiers that were specifically designed to be overdriven.

The Digital Revolution

In the last two decades or so we have seen the rise of other kinds of extreme processing powered by technology rather than electric instruments, tape or vinyl. Just as guitar amps opened up new frontiers, so did the advent of digital audio recording and sampling.

When digital samplers from AKAI and E-mu became affordable enough to find their way into the hands of regular producers, they figured out that there were some tricks the kit could do that hadn’t been seen or heard before. The most obvious one was extreme time- and pitch-stretching. Changing the pitch and time of recorded sound independently of one another wouldn’t become really easy until the advent of software, but in digital samplers the technique entered a sort of halfway house – with some interesting side effects. If you played a sample lower down on the keyboard, it would slow down and be lower in pitch. Similarly, higher meant faster. But it was also possible to stretch a sample far longer that its original duration, even when it was played on middle C. With tape, this always resulted in the pitch lowering, because tape is an analogue medium. In the digital hardware domain, however, something weird happened. The sampler sort of dragged sounds out, making them sound robotic and synthesized but without dramatically lowering the pitch. This technique was heard a lot in the big beat music of the late 90s, especially people like Fatboy Slim and others on the Skint label who would use it during breakdowns and tempo changes.

Digital hardware samplers also made it possible to play several samples at the same time, and although that sounds simple enough, the limited RAM capacities of the time meant that you had to set things up carefully. For reference, an early sampler would be considered high-end if it had 64MB of RAM – a fraction of what you have in your smartphone. Samplers also had built-in effects (or at least the more expensive ones did) and powered a generation of producers to create new kinds of music. AKAI’s S3000 series, for example, was used widely by pioneers of electronic and drum’n’bass music (Goldie, Plastikman, LTJ Bukem and Moby). The things it let you do with sounds – change them in ways not previously possible – gave birth to new genres. Jungle music with its speeded-up beats, for example, wouldn’t have existed without the sampler, nor would seminal records from hip hop acts such as Public Enemy.

Bring On The Software

Software sampling has rather changed things, of course, and these days even a basic software sampler offers far more flexibility than a hardware model did back then, simply by virtue of being able to leverage the power of a computer. Audio is truly flexible these days, with apps such as Melodyne able to offer previously unthinkable access to polyphonic audio, enabling you to ‘reach inside’ chords and even whole mixes and alter any constituent sound, even when lots of other sounds exist at the same time. You can take a major guitar chord recorded as a simple audio file, reach inside it and change it from major to minor. Or remove crowd noise from a live recording. Similarly, iZotope’s RX plug-in provides incredible access to the innards of digital audio waveforms.

This kind of technology gives rise to new kinds of extreme audio-processing tools, the roots of which can be traced back to Propellerhead’s ReCycle. You might not think of ReCycle as particularly extreme, but the concept of slicing up loops and beats and re-sequencing them or playing them live as a completely new kind of instrument is one that’s influenced not only the development of software plug-ins in the last two decades but also the kinds of music that people have made with them. We’re talking, of course, about glitch and cut-up music, embodied perhaps most suitably by many of the artists on Warp Records’ roster, such as Aphex Twin or Autechre. In fairness, acts like these tend to lead rather than follow, and Aphex Twin in particular has done at least as much influencing of the way software has evolved as vice versa. People wrote software to do what he was already doing by himself.

Mashing up is done not just in plug-ins but also in DAWs, and the ability to time- and pitch-stretch and edit in amazingly fine detail have all been important in enabling people to create intricate and complex arrangements, projects that contain tempo changes, huge variations in tone and so on. Some have even made their own mash-up tools, like Steinberg’s LoopMash. Plug-ins tend to rule the roost when it comes to slicing and dicing, however, and models like iZotope’s Stutter Edit demonstrate just what is possible. An incredibly powerful audio-manipulation tool, it applies and modulates multiple effects in real time based on your input, effortlessly repeating, delaying, bit-crushing and juggling audio in ways that are frankly astonishing. It is, really, modern electronic music in a single box.

Glitch processing is another popular kind of electronic production technique, involving both generating and processing sound in semi-random, stuttering and unpredictable ways. Again, there are plug-ins that can help you to do this, and it’s a lot easier than trying to actually program or play instruments to get the same effect. Stutter Edit is good at glitch, and Audio Damage makes some dedicated and capable tools as well. Its BigSeq, Replicant and Automaton are all excellent glitch plug-ins. Sugar Bytes is another leader when it comes to glitch tools: Turnado, Effectrix and Artillery provide an astonishing set of tools to let you easily create amazing, glitched-out soundscapes. NI’s The Finger is also an interesting contender.

With a setup like Serato’s Scratch you can mix, scratch and generally mess with music and live input.

Resynthesis Comes Of Age

In recent years, a new generation of synths has come of age, which can broadly be termed ‘resynthesizers’. Initially there was just the Camel Audio Cameleon, and that company now makes the more advanced Alchemy synth; iZotope’s Iris is a recent but very powerful addition to the lineup. These use a combination of a waveform or sampled audio file and various synthesis techniques to generate sound in completely new ways. They make it possible to ‘draw in’ parts of the waveform that are to be used to generate sound, which is passed to other stages including filters, LFOs and effects, and there’s often the option for parameter modulation, too.

Resynthesis is a curious hybrid of sample playback and synthesis – with a healthy dose of effects thrown in for good measure – and it can result in some truly unique and original sounds. That’s true when they are used on their own, but when plumbed into a wider project complete with programmed MIDI, audio effects and more, they can sound superb.

Another, perhaps less obvious example of extreme audio processing is one that’s been around for many years, albeit not always at the forefront of musical innovation. Vocoding and vocal processing came of age in the 70s with hits like ELO’s Mr Blue Sky as well as more esoteric, avant-garde music. Some early synthesizers, like Korg’s VC-10, had a built-in mic, and the signal sung or spoken into this was used as the modulator. The synth sound is the carrier, and so the notes that you hold and the settings on the synth itself determine the pitch and character of the sound that is ultimately produced. The most obvious effect for this is to make someone’s voice sound robotic, but it was also used by more enterprising producers to process all sorts of other sounds, resulting in some really interesting records. More recently, bands like Muse have brought vocal processing back to the forefront of modern production, and are probably the best example of using harmonizers and kit like TC-Helicon’s VoiceLive and Roland’s VP-7 vocal processor to create advanced, layered vocal parts both in the studio and live onstage.

TC-Helicon makes some advanced vocal processors that can add harmonies and multiple effects to any vocal signal, for everything from subtle to extreme effects.

Up To Date

Pitch-correction (or auto-tune) is another technique that has been diverted from its original intended use and press-ganged into service as a musical phenomenon. The technique of ‘hard-correcting’ a vocal with an auto-tune unit to the point that the notes ‘step’ abruptly from one to another was probably first popularised on Cher’s hit Believe, but has since spread to whole sub-genres of pop music thanks to artists like T-Pain. It’s an acquired taste, but as a technique it doesn’t seem to be on its way out yet.

Another style that takes no prisoners is dubstep, which in its more extreme forms uses heavily modulated bass sounds as well as insistent, high-pitched, arpeggiated synths to mount a sonic assault. It’s all about extremes – of low and high frequencies, of speed, volume and the regularity with which it changes. It also tends to be mastered very loud and, like some other forms of electronica, often doesn’t involve any real instruments, with everything being generated in-the-box by software.

Extreme processing takes many forms, from heavy guitar distortion through glitch, bit-crushing, delay, reverb and speeded-up beats to completely hyperactive mash-ups and thunderous sidechained kicks. Music that’s all heavily processed sounds pretty extreme, but you can use it as much or as little as you like. Dirty-up the vocal but not the beats, or use heavy guitars over clean vocals. The choice is yours, and there are now more tools for working with extreme audio processing than there has ever been before.