Modular Synth Tutorial: Eurorack Filters: Which and Why

Chances are, somewhere in your Eurorack, you’ll have a filter – but the ones you use could seriously colour the music you make. Dave Gale gets fab with filters… Allan Hall’s beautifully crafted clone of the Moog Transistor Ladder design Back in the 60s, as concepts for new types of sound creation were being born, […]

Chances are, somewhere in your Eurorack, you’ll have a filter – but the ones you use could seriously colour the music you make. Dave Gale gets fab with filters…

Allan Hall’s beautifully crafted clone of the Moog Transistor Ladder design

Back in the 60s, as concepts for new types of sound creation were being born, so was the concept of a type of synthesis known as ‘subtractive synthesis, which we now often call ‘analogue synthesis’ by accident, although the parallels are there, thanks to the circuit designs of the time.

It was our beloved grandfather, Bob Moog, who took the concept on and brought it to the masses – thanks to his modular designs and then the more-affordable MiniMoog, which we now see back in production (although for many, it never went away).

Time for a Eurorack Filters Recap

To fully understand what filters do, we have to start with the oscillator – which, as most of us know, is the bit that makes the noise, through a series of pulses that, when increased in frequency, rise in pitch.

However, possibly the most interesting aspect to the oscillator is that different oscillators can create different tones: some large, some pure, but certainly in the case of subtractive synthesis, the larger the better.

This is exclusively down to harmonic content; the more harmonics that are present, the bigger and brighter the oscillator sounds; and with this comes an inherent rise in volume, or amplitude, as we call it.

No surprise, then, that the stalwart waveforms of subtractive synthesis, namely the Sawtooth or Square wave, are rich in harmonic content, giving us plenty to work with.

With our ‘large’ sounding oscillator in operation, we want to tame some of those harmonics, and we do this by using a filter, or series of filters, to remove the harmonics we don’t wish to hear. Think of your oscillator as an unkept tree, in your garden. Every now and then, you’ll want to remove some branches (harmonics) and get it back into shape.

Well, that’s what you do with a filter, except the filter in a modular, or on a synth, is debatably the single most important component for tonal colour, and your choice of filter will have a great effect on the way your music sounds. This is, in part, thanks to a control which is present on most filters, called ‘resonance’, which literally resonates the point where you decided to close the lid on the harmonic structure of your sound – creating that whistling effect, rather like feedback.

The Highs and Lows

When it comes to using your filter to shape your sound, you may well be confronted with anything up to four modes of operation, which is all to do with which frequencies are removed from the harmonic content, and which are allowed to pass.

Hence the most common filter by far is the Low Pass filter (LPF) which, when opened from left to right, will reveal an ever increasing soundscape of harmonics; but when closed from right to left, will reduce the tonal quality of the timbre, right down to its fundamental – which is essentially a sine wave – playing the note you have pressed down on your keyboard or sequencer.

You will hopefully have noticed that the clue is in the name, as the low frequencies (pitches/harmonics) are the ones that are allowed to… well, pass! By the exact opposite process, if you have a High Pass filter mode (HPF), you will notice the same thing occurring upside down, meaning the higher frequencies are allowed to pass. This can be especially interesting on bass sounds, as you get the sense of the bassline, but without all that low end, which can sound really eerie, but also great.

Less-common filter modes are Band Pass and Band Reject, where the band width, which can often be set on the filter, will be the area that either allows frequencies through in the case of the Band Pass (BPF), or rejects them in favour of the frequencies either side of the band in the case of the Band Reject (BPR). Although less common, they are also incredibly useful, so worth looking out for if you want something a little different.

The one that started it all: the filter from the Mini Moog, complete with basic envelope controls

I often find myself using these sorts of filters for quite ‘domestic’ duties. Say I have created a nice hi-hat-type sound, using all manner of patching. It’s quite likely that I might get wisps of low end infiltrating my timbre: so I will plug in a second filter to discard the frequencies I don’t wish to hear, a little like a harsh EQ, and here, the parallels between filters and EQ come into play. They have many similarities.

As previously mentioned, the Resonance control (sometimes described as ’Emphasis’ or ‘Q’) will also heavily affect sound creation, as it resonates the point of cut off. The more you crank the Res, the more it’ll rip into your head, and therefore might just jump out at you in a subsequent mix.

Ladder Designs

Without doubt, Bob Moog has to take the most credit for providing us synthesists with the most ubiquitous of designs in the form of the classic Moog Ladder filter. Bob invented this at the time that transistors were appearing, so it’s often described as a Transistor Ladder Filter. You’ll hear this design on just about every Moog that’s in production, and it has a certain charm and beauty.

Certainly, I am a big fan of the Ladder Filter on the Moog Voyager, mainly because of its slightly updated ‘dual’ design, which can offer some amazing stereo effects. Strangely, at the present time, you cannot buy a Moog Ladder Filter directly from Moog for a Eurorack without having to make do with some form of synth channel, such as the Mother-32. It’s no slouch, but not what you want if you just want a filter.

You could also consider the Moogerfooger MF-101 Lowpass Filter pedal, which is also based on the classic design… but is essentially a pedal, so there may be impedance and level issues when integrated with Eurorack kit.

So the answer might be to look at a clone, such as the AJH Synth MiniMod Transistor Ladder Filter, which is modelled on the original Mini Moog design, with a rather alarming level of accuracy.

It’s so close you would be hard pushed to tell the difference from the real thing. However, AJH – being clever bods – have attempted to look after an attribute of the original design, which many see as a limitation.

When the resonance is increased, the lower frequencies are also decreased, meaning that there is a drop in the level and also overall ‘oomph’. This is not a criticism, it’s just what this filter does. But it can be a bit irritating, so AJH have implemented a jumper, which can be removed, which will put some of those lower frequencies back in place, by overdriving the bottom end. Clever stuff, and more to the point, really useful when you’re creating timbres to place in a mix.

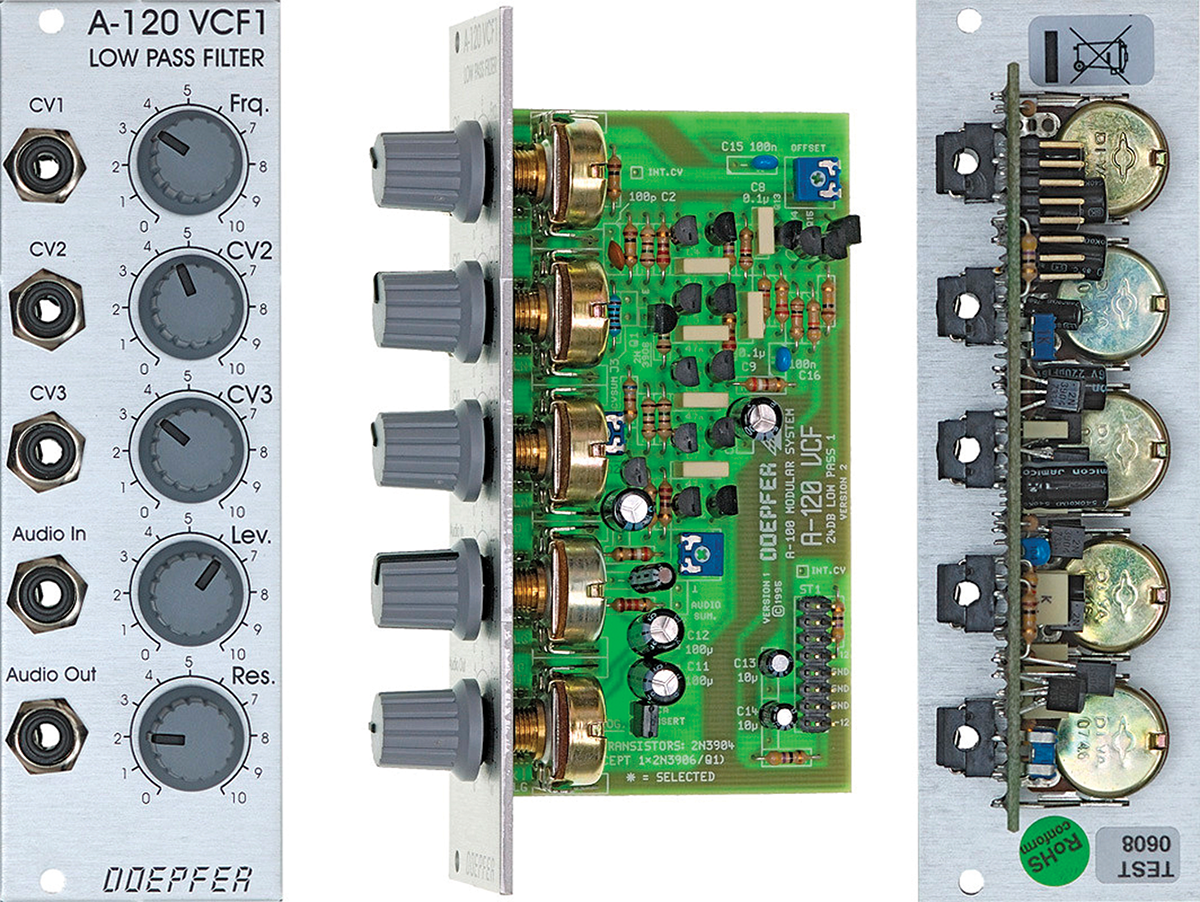

Winning the ‘bang for buck’ category, the A-120 from Doepfer represents superb value for money

East is East, and West is West

It’s worth noting that subtractive synthesis is often described as an ‘East Coast’ attribute. So what does this refer to? It essentially harks back to the original design days, when the likes of Robert Moog, based on the Eastern side of America, was rivalled by other synth pioneers, such as Don Buchla, firmly based on the West Coast. While Moog was working on the idea of subtractive synthesis,

Buchla was working on another concept, to do with adding harmonics, rather than taking them away, which is known predictably as ‘additive synthesis’. Buchla was also working on a host of other concepts, such as frequency modulation and the use of touch plates, but the East Coast/West Coast ideal has stuck, and is often referred to in Eurorack circles.

The Other Moogs

As we’ve already mentioned, it’s not possible to buy a Eurorack filter from Moog at the present time (a situation I think will change in the near future).

So, in the meantime, what other choices are out there? Studio Electronics calls its Moog-style filter design the 5089 Filter and it has the usual great SE sound and build quality, along with additional features such as CV control of resonance. If you’re after something affordable, on the other hand, the Doepfer A-120 ladder filter will give you a hint of Moog on a budget.

Diode Ladder Design

Another interesting Moog design of filter came in the shape of the Moog Musonics Sonic V filter, which was a Diode Ladder design. Strangely, one of the reasons for going with this design was to sidestep the patent, held by Bob Moog, who had left his own company by the time the Musonics Sonic V was in development.

There are obvious similarities to the Transistor Ladder discussed earlier, but it feels as though it has a fuller body of tone, and has a much wispier top end, with less of the bottom end falling out of favour once the resonance is cranked.

AJH Synth has again modelled this filter (the Sonic XV Diode Ladder Filter, reviewed in issue 163), with its tremendously faithful attention to detail, and thanks to the excellent build quality, for all intents and purposes, it may as well be a Moog filter.

Either the Transistor or Diode Ladder designs will give you an exceptionally rich tonal colour, one which for many is unsurpassed, even now. However, it’s a tonal colour that could also be considered quite vintage in its sound, so next issue, we‘ll move away from Moog and instead, take a look at the wealth of other filters that are available to Eurorack users. So stay tuned for more features and greater tonal colour, as we delve further into the filter bank…