Getting A Vintage Sound: May The Source Be With You

As today’s recording processes hark to past glories, never have classic sounds been in such demand. John Pickford examines the history, the processes and the gear that made classic recordings sound so good and endure for so long – and shows you how to recreate vintage vibes with today’s gear… Before digital recording became the […]

As today’s recording processes hark to past glories, never have classic sounds been in such demand. John Pickford examines the history, the processes and the gear that made classic recordings sound so good and endure for so long – and shows you how to recreate vintage vibes with today’s gear…

Before digital recording became the industry standard, most home recordists (as they were once known) had to make do with sub-standard, semi-pro recording gear to lay down their tracks. Likewise, many small ‘demo studios’ offered cheap and cheerful multi-track recording, by using entry-level mics through poor-sounding mixing desks onto compromised tape machines. During this period – we’re talking mainly the 1980s and 1990s – some engineers lucky enough to have acquired an old mixing console from the late 60s, or a mid-70s 16-track tape recorder, found that compared to modern, budget gear, vintage equipment sounded far superior.

Nowadays, both home-based producers and professional studios alike have access to first-class hardware and software, much of which is either based upon or a clone of classic vintage designs. What’s more, much of this kit is affordable and no more expensive than the nasty-sounding budget gear that flooded the market 25 years ago. The main element of modern recording practice that differs from sound recording’s glorious past is the lack of multi-track analogue tape. Although some diehards lament the demise of tape recording, the truth is that digital recording is now so good, even top-flight professional studios that still own an old 24-track recorder conduct most of their sessions in the digital domain. It’s wonderful bedroom producers can now enjoy the same quality of recording medium as the biggest and most expensive studios in the world.

While the recording industry has rightly embraced digital recording as its future, for the creation of world-class sounds, it now often looks to its past. Long-established companies such as Neve and Universal Audio offer authentic versions of their classic designs, while newer manufacturers compete by producing superb-sounding recreations at affordable prices. And now that digital modelling has improved immensely, engineers can enjoy any number of Pultec EQs, Fairchild compressors and UREI limiters without owning a single piece of outboard hardware.

May the source be with you

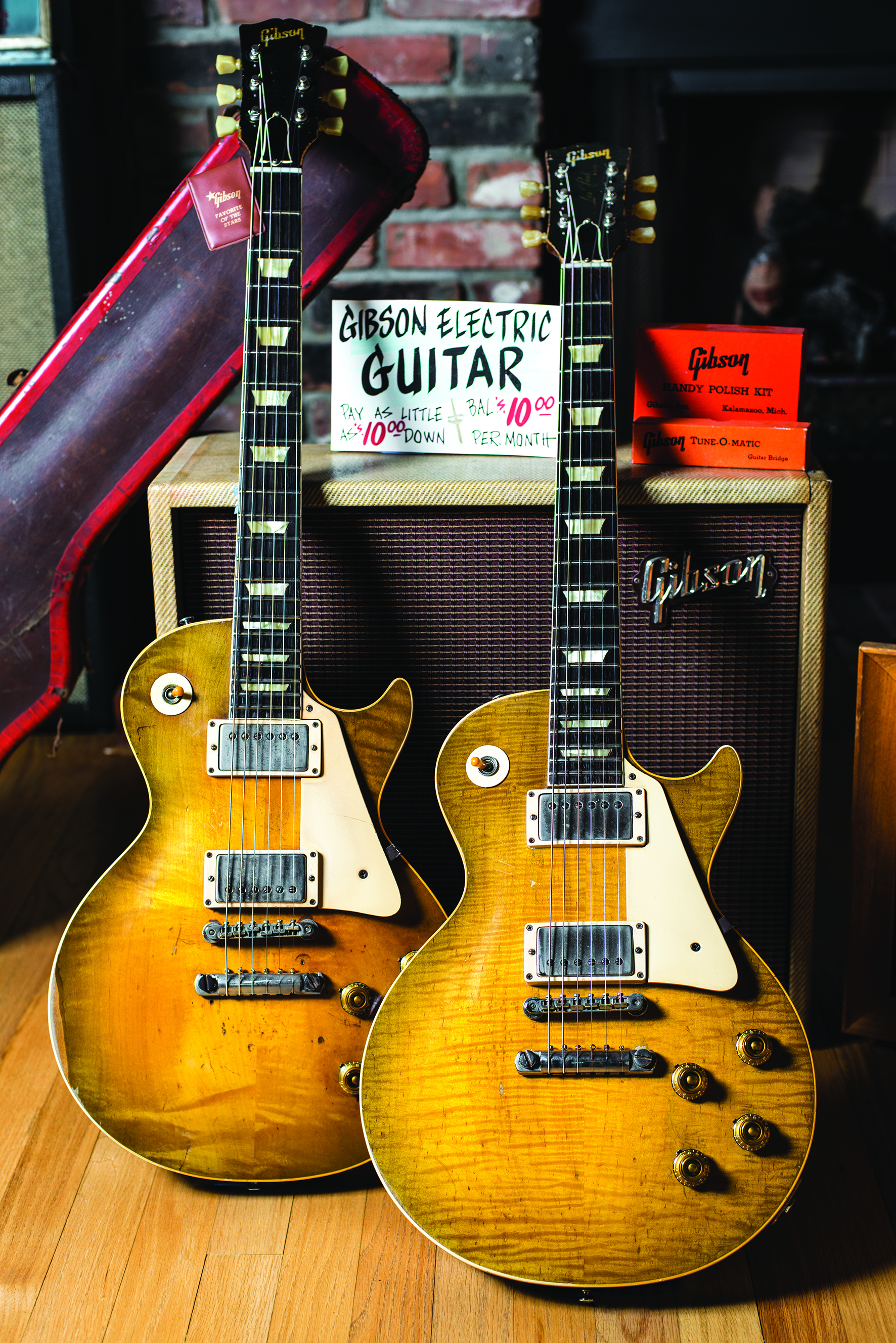

The availability of vintage audio designs is a fairly recent development in pro audio – however, the guitar industry has never lost sight of its roots, which is why generations of guitarists, for the most part, still use close relatives of the Fender and Gibson models that first appeared in the 1950s, rather than modern designs. This is the fundamental point: vintage sounds have to be created at source and no amount of classic mic-preamps or iconic compressors is going to give authentic results if the source sound isn’t correct. Likewise, to emulate the sound of classic pop sounds from the 50s, 60s and 70s, an understanding of the recording methods employed back then is vital – which is what we’ll be showing you over the next few instalments.

Of course, vintage sounds can be classed as anything from 50s rock ’n’ roll to the New Wave sounds of the late 1970s. However, in this guide, I’m going to explore classic vintage sounds that incorporate guitars, drums, organs, acoustic instruments and vocals; vintage synthesisers are a subject for a future feature.

Starr sounds

Ringo Starr’s drum sound on The Beatles’ recorded output from 1962 to 1970 has been the envy of recording engineers for decades. Their original engineer, Norman Smith, recorded all of the group’s early hits and albums up to and including 1965’s Rubber Soul. He never used more than two microphones on Ringo’s kit, firstly employing an STC (Coles) 4038 ribbon as the main overhead/kit mic along with an STC 4033-A on the bass drum. Around 1964, these mics were substituted for an AKG D19c overhead and AKG D20 on the bass drum. The combined mono signal would be sent to EMI’s RS124 compressor, now reissued by Chandler Ltd.

When Geoff Emerick took over in time for 1966’s Revolver album, he augmented Smith’s set-up with a Neumann KM56 condenser mic underneath the snare drum. By the following year’s Sgt. Pepper… album, he’d added three more D19c dynamics to close-mic the rack, floor toms and hi-hat. The combined signals would be sent to a mono Fairchild 660 limiter with fast response times and often a 10kHz top boost was added. Ringo often placed a thin tea towel over his snare and toms, for a drier tone with less ring.

Rock ‘n’ Roll pioneers

Historians have debated for decades over what was the first rock ’n’ roll record, but we’ll start where the recording studio itself first played an integral role in the development of a new sound. Sun Studio, founded by Sam Phillips in Memphis, Tennessee, not only produced what many believe to be the very first rock ’n’ roll 45, but also the first recordings by the world’s first true rock icon – Elvis Presley.

Rocket 88, recorded by Jackie Brenston And His Delta Cats (featuring the song’s composer, Ike Turner), was a pioneering, piano-driven R&B jive record cut at Sun Studio in 1951. However, three years later, Elvis Presley defined the early rock ’n’ roll sound when he performed That’s All Right (Mama) live in the studio along with Scotty Moore on electric guitar and Bill Black on upright string bass.

No drums were featured on the recording, but producer/engineer Sam Phillips added excitement by feeding Presley’s vocal back through his tape recorder to achieve an echo (delay) effect that became known as slapback echo. This effect employed a single repeat echo with a delay time between 60 and 120 milliseconds.

Early examples of tape echo were created using the studios’ professional tape machines. However, as the effect became more widespread, dedicated echo units, such as the Watkins Copicat and, later, the Roland Space Echo would often be used. When digital delay units first appeared, engineers discovered that the identical repeats lacked the organic, degenerative sound of analogue tape.

Thankfully, modern digital simulations factor in this quality for a more convincing, vintage sound. Dedicated analogue tape-echo units can be expensive; however, I’ve achieved great results from using a cheap old cassette player, feeding signals through it then sending the cassette recording back to a separate track in my DAW and moving the analogue sound digitally to produce the desired echo/delay time. This is a great way to achieve an authentic analogue-echo sound cost effectively, using modern methods within your DAW.

During this period, pop recordings were produced with vocalists singing live along with musicians and recorded directly onto a mono tape recorder. The lesson to be learnt here is that before multi-track recording became standard, the recording and mixing process was interdependent, requiring the engineer to get each individual sound perfected and balanced as the performance was committed to tape.

I mention this because, with the advent of multi-track recording and today’s unlimited track counts, it can be tempting to record sub-standard sounds to save time, believing that they can be dramatically improved later. This ‘fix it in the mix’ approach is rarely a better option than getting a great sound before hitting the record button.

Vintage verb

Some of the bigger studios in the 1960s and 70s housed echo chambers; however, many more relied on electro-mechanical devices such as plate and spring reverbs. The smooth-sounding EMT 140

Plate Reverb – perfect for vocals and all manner of instruments – has been used on thousands of recordings, and excellent software emulations are available today.

Spring reverbs have a nicely trashy sound that lends tracks an unmistakably vintage vibe. Software versions are available; however, many old guitar amps contain a spring unit, perfect for adding a genuine analogue touch to any sound, not just guitars.

A top tip for vintage ’verb is to EQ the signal before sending it to the reverb. Roll off frequencies below 600Hz, to avoid low-end rumble that will boom within a mix and cut extreme top above 10kHz, to accentuate the midrange frequencies.

Most engineers would delay the send to reverb via tape or a delay drum; however, a suitable pre-delay can be achieved by simply printing the reverb to its own track, then moving it forward within your DAW. Further EQ – boosting the mid-frequencies, for example – will add to the vintage colour.