Paul Epworth on making Voyager, his psychedelic debut album

The six-time Grammy-winning producer is taking a leap of faith with his debut solo project: a through-playing concept album exploring the outer reaches of record production. We talk astral projection, alien voices, and putting distortion on absolutely everything.

“I knew I was going to be sort of a jack of all trades and master of none,” says Paul Epworth, remembering the early days of his career. Yet, the producer has received awards on stage at the Grammys, the BRITs, the MPG Awards and even the Oscars.

Just his work with Adele and Bloc Party has left an indelible mark on British culture. And, despite his deliberate, crunchy sound he’s also been able to fall in line with even that most formulaic of musical sub-genre: the Bond theme. Epworth co-wrote 2015’s Skyfall with Adele. Its grand Shirley Bassey stylings saw it reap a bevy of awards and become one of the most beloved Bond themes in the franchise’s history.

But all the while, Epworth has yearned to do something more experimental, more personal. “I’d always had this idea that I’d one day make an album where I was able to take the time to explore the records that I’ve loved over the years,” he says, “and really explore the art of record production.” The result of that yearning is Voyager, an unabashed sci-fi concept album in the vein of 1970s space-rock epics, centred around themes and sounds driven in part by Epworth’s childhood musical experiences. But though his first-ever album of original music has been on his mind for a long time, by music-industry standards at least, it took eons to materialise.

“I signed a deal 10 years ago,” says Epworth, “and then a lot of other things just got in the way.”

“With suddenly being in demand, and people wanting to work with me, and me then having a family, I put it the album on the back burner,” he explains.

Being in demand is an understatement. Over the past decade, Epworth has worked on scores of high-profile projects with many of the biggest names in the music business, including U2, Stormzy, Rihanna, Paul McCartney, Mumford & Sons, and Beck. But the push to summon Voyager into existence came while working with Lianne La Havas, during the writing of what would become her 2015 album Blood.

“I’d made a track with Lianne La Havas called Unstoppable,” says Epworth. “We wrote this big psychedelic soul thing influenced by Attilio Mineo, Sun Ra and Quincy Jones. Working with her was incredibly inspiring.” Though the pair wrote many songs during the sessions, only this one made the cut. But La Havas identified in Epworth a clear love of writing and suggested that he use the unused tracks for his own means. Though they wouldn’t make it onto Voyager, the notion helped crystallise the idea that he could one day be a recording artist himself.

With that idea resonating, Epworth began his self-described journey into outer space to make the record. “I was born in the 1970s and grew up with my parents’ record collection,” he says. “My dad had all these strange electronic records by the likes of Isao Tomita, Wendy Carlos, and Jean-Michel Jarre, as well as The Dark Side of the Moon.”

Pondering on his childhood introductions to music and these early electronic and psychedelic influences, Epworth felt that they were somehow connected to contemporary labels such as Flying Lotus’s Brainfeeder, and with the LA and south London jazz scenes. “It was stuff that felt very relevant,” he says. “I thought, ‘What if I was to make this kind of big, ostentatious 1970s space concept album but for a modern audience, and try and flip it?”

The many points of inspiration, from analogue-led Japanese proto-trance to Afrofuturist avant-garde US jazz, make Voyager a typically slippery record to pin down. When pressed on how best to categorise it, Epworth suggests “space jazz”. It’s like a mixtape, he says, in that the record touches on so many different genres. But he’s certainly not shying away from its 1970s roots, nor his more out-there, psychedelic ideas.

The track Binaural Trip, for example, begins with a binaural recording that the Essex-born producer says is supposed to encourage astral projection. “I thought it would be funny,” he says. “If I stick this through the entire song then, by the end of it, people might have left their bodies.” He and his collaborators voiced the track’s chords around the tone so that they could use it throughout most of the song. So does it really inspire astral projection? Only one way to check.

Psychedelia and themes of space exploration run throughout the record. Elsewhere, you’ll hear what sounds like pitched-down mumbling, which is actually Epworth reading from a book on ayahuasca, a South American psychoactive brew. Elsewhere still, you’ll hear Epworth trying to recreate the sounds of aliens communing with man, that he heard during an eventful DMT experience.

These ideas of visiting strange worlds are further supported by a few high-profile samples. A recurring refrain from Dusty Springfield’s cover of The Windmills of Your Mind underpins the opening to the title track before it’s hit by thumping four-to-the-floor kicks. You’ll also hear moments from Jerry Goldsmith’s groundbreaking score to 1968 sci-fi film Planet of the Apes. Epworth was even fortunate enough to get sample clearance for one of the tracks from Sun Ra’s 1974 experimental sci-fi film Space Is The Place, also scored by the artist.

The version of Voyager the concept album released September 11 is not Epworth’s first attempt at making this record. His first effort, he says, was not up to scratch. “When you’re a producer, you’re helping artists who have a vision, an identity, an idea of who they are and of what they want to make an album about. You have to formulate that stuff. I had this collection of songs but they had no identity and no depth. It wasn’t very good and I had to be brave enough to go, ‘Well, no-one needs to hear this.’”

Finding that concept and hewing that identity took time. For a producer, whose role is so often to support and facilitate, Epworth says making the time to find that concept sometimes felt like a selfish pursuit. But by beginning with a loose conceptual framework,

he was able to dive into his own feelings about what Voyager’s true message should be.

This process highlighted an area where Epworth felt he had been lacking as a producer. With all the technical trappings of production, it’s all too easy for producers to forget the challenges facing the artists they’re working with

“I suddenly realised that I probably hadn’t cut the artists the necessary slack,” he says. “How hard that was, as a process of self-examination. You’re digging through the dirt to find diamonds. It was tough, and you go to places in your psyche that you probably didn’t necessarily need to go.”

The result of Epworth’s inner explorations was that he was able to have better conversations with his guest vocalists. He also came to a realisation about the project: space had become a metaphor for lots of other stories.

Thinking like an artist

Epworth’s advice for aspiring self-producing artists is straightforward. “To be an artist,” he says, “you’ve got to have something you want to say. You don’t necessarily need to work it out beforehand.” But given the ease with which fledgling artists can get their hands on music-production tools, many of which come readily packaged with the big DAWs, he also recommends some self-imposed limitations.

“You could do a Derek Jarman and make a movie or an album about colour. I remember hearing stories about Lalo Schifrin going into a class at Berkeley and saying, ‘Today, you’re going to learn how to play orange’. Whatever the key is to get you into the room. It could be a book. It could be a drug experience. It could be limiting yourself to doing it on three instruments or three guitar pedals. It’s all about finding what those are for you. It could be working in 8-bit or using an Emagic soundcard from 1995. Find a colour palette, a concept or an identity. Then, once you’re in, ask yourself, ‘What is it that I want to say?’”

Epworth even encourages producers to try this approach to further their craft. “Even if it’s not for you as an artist, these things will help you ask those questions and offer those pieces of advice, comfort and analysis to the artists you’re working with.”

Not satisfied with merely making a concept album himself, Epworth decided that one of his limitations should be that the whole record was a single piece of music. To make it so, he key-related the songs, structured the running order and shifted the keys of tracks to make them flow together in a musical way. Voyager essentially became a single 60-minute song.

Though there are single edits of several tracks, the album has been meticulously crafted to be experienced from start to finish in a single sitting. Epworth is candid about the rationale behind this complicated route. “Initially, I thought, ‘If the songs aren’t good, at least I know I’ve got the framework to do something that feels like it’s been well crafted,’” he says with trademark modesty. “But thankfully we’ve ended up with a couple of good songs on it.”

The technical challenges posed by this ambitious undertaking, however, were significant. Changes to any one track had the potential to affect the next, and there would then be knock-on effects across the record. Second track Hyperspace, for example, was explicitly designed as a bridging track between the anthemic opener Mars & Venus, which features vocals from Vince Staples, and the more meditative track OBX that follows.

To ensure the songs flowed smoothly from one to the next, Epworth had a bounced version of the next track’s opening bars sitting at the end of each project file for reference, and the reverse at the start of each session, to ensure the tracks started in a way that worked as part of the whole.

Some of these track overlaps were more than a minute long. These elongated bridging sections, needless to say, didn’t translate to the tracks’ single edits. Not wanting to compromise the integrity of the concept album, though, an extended string outro penned by prolific pop string arranger Sally Herbert on Love Galaxy became its own separate track. And so, a 12-track record, with all its musical connective tissue, became a 15-track record.

To reinforce the idea of a journey through time and space, Epworth wanted the record to sound modern at the start and then go backwards in time as it went on. This notion of blending old and new is reflected in his choice of instruments too. Thankfully, his recording space, The Church in London’s Crouch End – previously owned by Dave Stewart of the Eurhythmics and singer-songwriter David Gray – is replete with vintage gear and instruments.

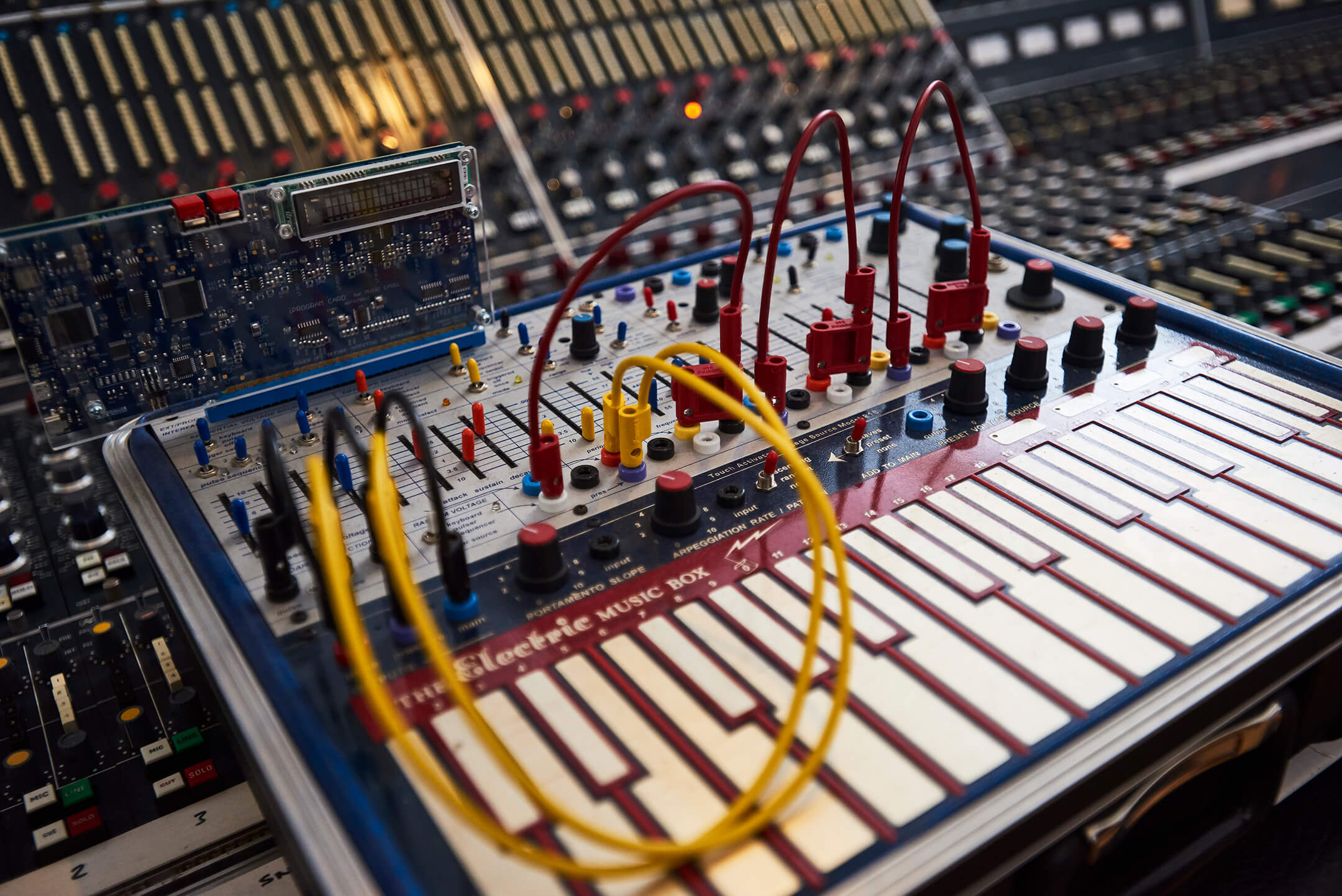

“We couldn’t have made it without the Mellotron,” says Epworth, who also name-checks

a roster of rare synths that includes the Gleeman Pentaphonic, the ARP Odyssey, the Oberheim OB-X, and the Korg PS-3300 polysynth, as well as the Minimoog Model D. But it wasn’t just vintage hardware that was called into action for Voyager. For the record’s more modern sounds, Epworth went digital, and chose to use a staple of EDM: Xfer Records’ wavetable soft-synth Serum.

“There were a couple of patches on Serum that we used repeatedly,” he says. “With organs and big EDM risers, it just gave them this super-modern sound and excitement. The sound is just a bit more digital than some of the old analogue gear we’ve got here, and when you layer up one of those patches with a Buchla Music Easel – which we used loads over the record – you’d end up with something that sounds really rich.”

Oddly enough, the Moog Modular that dominates an entire wall of Epworth’s studio space didn’t feature heavily on Voyager. However, he did make smart use of his Eurorack system when it came to the record’s sound design. Specifically, he used Make Noise’s Morphagene module, loaded with vocal loops from British singer Lil Silva, to create what he describes as “a weird, glitchy, Arthur Russell-ish kind of thing”.

Indeed, it’s this broad knowledge of left-of-centre music that fuelled the producer’s desire to make a record that’s such a departure from the rest of his more commercial work.

“That was part of the approach,” he says, “to make music that references the artists and music that I’ve loved over the years in a way that wouldn’t be obvious, especially when compared to some of the records that I’m more well known for and to just do something that didn’t really have to have a commercial aspiration. It was more about doing something that I felt was a piece of artistry and not consciously trying to please anyone else.”

Star fleet, assemble

In contrast to his practically limitless collection of high-end gear and instruments, Epworth’s pool of collaborators for Voyager was relatively small. It’s not as if he doesn’t have an impressive list of contacts. It was more about finding collaborators who would understand the concept and invest themselves in it. Two of those were Harry Edwards and Riley MacIntyre.

“Harry is an amazing artist in his own right,” says Epworth, “who we work with here at our label Wolf Tone. Riley, my engineer, was my co-pilot throughout the whole thing. It was mainly the three of us.”

Beyond that creative nucleus, Epworth also drafted in trusted keyboard player Nikolaj Torp Larsen. “He had the necessary skills and musical understanding to be able to expand the ideas, and he’s an amazing jazz player.”

The record also features a cast of guest vocalists that include Vince Staples, Lianne La Havas, Ty Dolla $ign, Kool Keith, Lil Silva and Jay Electronica. But cementing their place in the project wasn’t straightforward and, while Epworth downplays the complexities, reading between the lines it seems like there were other guests slated to get involved but who backed out of the project late into its production. But the producer, ever the professional, doesn’t name names, and remains remarkably cheerful about it. “Hopefully, one day, the director’s cut will come out.”

Aside from bringing in guests, the production process for Voyager was largely similar to any other Epworth project, beginning with his chosen DAW: Logic Pro. “There’s something about the creative freedom and the speed at which you can do stuff in Logic,” he says. “It’s much easier to harness a creative idea. It’s what I started out on.”

“There’s something about the freedom and the speed at which you can work in Logic”

It’s in Logic that most of the record’s drum programming took place. By his estimation, Epworth programmed about 65 per cent of the album, with artist/producer collaborator Harry Edwards working on complex additions, fast hi-hats and all sorts of other manipulations.

The production bounced between DAWs, depending on the task. Pitch shifting was handled

in Ableton; mixing largely done in Pro Tools. The team also took advantage of Pro Tools’ half-speed playback mode to make more psychedelic sounds, which were recorded out into a separate rig.

Space Oddities

The experimentation continued throughout the entirety of production. The album’s sequencing had been set in stone as far back as 2017 but, when Epworth received a vocal from Ty Dolla $ign for the track Cosmos in January 2019, he was still inclined to play around with things, and ended up smashing two tracks together.

Ty had recorded his vocal on a Space Oddity-inspired acoustic guitar track that originally ended in a “grand Mellotron-orchestrated ending”. “I just thought, ‘How can I flip this?’ says Epworth. “So I tried sticking this other track at the end and putting his vocal over the other song. The second half morphs into a track where I was trying to do some sort of Steve Reich Six Marimbas cyclical-arpeggios thing with the modular. So it starts with this beautiful, euphoric, positive thing, where Ty sounds like he’s singing about love, then it flips and sounds like he’s singing about being addicted to drugs. The whole mood of the track changed even though it’s the same piece of vocal.”

With all of these experimental tracks created in between other Epworth recording projects over the course of several years, the producer ended up having to deal with a monstrously large number of tracks. “On some of these tracks, we maxed out the Pro Tools track count,” he says, with a mixture of surprise and glee. “We were trying to make commitments and avoid making commitments because, for some songs, the vocals didn’t end up on the tracks until after I finished the masters.”

As any bedroom producer will tell you, maintaining perspective on a project that you’ve spent a long time working on can be tough. So, to rationalise the enormous projects, Epworth handed them over to LA-based mix engineer Mike Dean.

Kitted out

If you were to define the Epworth sound, you couldn’t couldn’t get away without mentioning great-sounding live drums. But, with Voyager, the producer-cum-artist took another left turn.

“Because there are so many records I’ve made with live drums on them, I intentionally set out to make almost all the drums on Voyager electronic,” he says. “There are occasional drum fills here and there but even when there was a live kit played, we sound-replaced and reprogrammed around the drummer’s feel.”

One example of canny percussion can be found on single Love Galaxy, which features drums played by Leo Taylor from UK alt-rock outfit The Invisible. “The live kit is just a flavour among the stuff we programmed around it,” says Epworth. “I was trying to do a 1970s fusion record the way Dr Dre would have done it.”

Part of that Dr Dre aesthetic literally involved layering samples from a Dr Dre producer pack, along with sounds made on the Mutable Instruments Eurorack module Braids. Even without live drums, though, the tracks still retain the characteristic Epworth sound, and that flavour might be boiled down to a smart trick that he uses across the board but specifically on drums. Pay attention: it’s a technique that can be used on virtually any production.

One of his secret weapons is FKDRUM PARA, and it’s been a feature of his productions for years. The parallel bus comprises two UAD Empirical Labs FATSO tape-simulator plug-ins, both maxed out. These are accompanied by a low-end bump in the EQ and

a small cut in the high-frequencies.

“You can spend ages trying to make your track sound perfect,” says the producer who came up working with indie-rock acts, “but sometimes you’ve just got to give it some fucking teeth.”

Epworth learnt this lesson relatively early in his career, when he was frustrated with a mix he was working on for his old band Lomax. “It just wasn’t hard enough,” he says. “So I stuck distortion plug-ins on everything and I was suddenly like, ‘Oh yeah, there we go’. That’s what recording to tape does. That’s what bringing it back to a board does.”

“I stuck distortion plug-ins on everything and was suddenly like, ‘Oh yeah, there we go’”

It’s not an approach that’s exclusive to Epworth though, who tells us how producer Flood would crank the tape monitors so that there’d be a bit of crunch when mixing on a console. “We use distortion plug-ins on everything, partly just to bring out the harmonic content so that things have character,” he says.

Having won all of his Grammy awards for his work with Adele – one of the most powerful and distinctive voices of her generation – it’s probably worth hearing Epworth out when it comes to vocal productions.

The one tool he strongly advocates using is a multi-band dynamic processor. “I like multi-band dynamics,” he says, “that comes from knowing that every vocalist has different resonances, depending on their physiology.”

If you’re dealing with a singer that has a problem frequency in the mid-range, Epworth suggests using a dynamic EQ. “It’s much easier to deal with that like a de-esser but for mid-range, especially for their sinus resonance. You can really easily tuck that out of the way.” Plus, because the dynamic EQ will only act when the problem frequency is present, it won’t overly colour the singer’s voice.

With the Mike Dean Voyager mixes complete, it was time to sequence the record once and for all – a process that happened in Pro Tools, with each song being nudged back and forth on its own track to reflect the song overlaps in the original sessions. But, at the end of the process, when it came to recording the entire 60-minute album out as a whole, they didn’t just hit Bounce to Disk and put the kettle on. They went further.

With the Mike Dean Voyager mixes complete, it was time to sequence the record once and for all – a process that happened in Pro Tools, with each song being nudged back and forth on its own track to reflect the song overlaps in the original sessions. But, at the end of the process, when it came to recording the entire 60-minute album out as a whole, they didn’t just hit Bounce to Disk and put the kettle on. They went further.

Epworth and Dean printed the masters from Pro Tools into another rig running Ableton at 176.4kHz/32-bit, which Epworth maintains sounds better – even though the record was mixed at 88.2kHz and recorded at 44.1kHz.

Epworth admits that, by this point, he’d spent too long with the record.”It’s a testament to Riley’s amazing engineering skills, his patience, and our connection, spiritually,” he says. “But also, at the end, I couldn’t listen to it. So I had to go, ‘The universe is making this record what it is, and any mistakes, any flaws, it just is what it is…’ But Riley still sat and listened to 3,000 stems and had to downsample from 176.4K.”

Next mission

So, might Voyager mark the beginning of a new and more exploratory era for Paul Epworth’s productions? “If I’ve got an opportunity and the time to make records with people and I’m able to be this obsessive over it, maybe,” he says. “But that’s not the case. This has been a journey of self-indulgence that might nosedive my career but, at the same time, I needed to say to myself that I did it, and that it was the best I could do with the resources I had.”

The record is a feat of technical and musical mastery, it’s one that is befitting of a master producer and certainly not a jack of all trades.

Voyager is out on Columbia Records on now. Stream it now on Spotify, Apple Music and Tidal. To stay up to date with Paul Epworth, visit paulepworth.com.

Read more artist and producer interviews here.